The Strange Death of Moustapha Akkad;

Zarqawi and “Halloween”

The ironies and dangers of globalization are tragically epitomized in the death last week of Hollywood director Moustapha Akkad at the Radisson SAS in Amman at the hands of an Iraqi suicide bomber. Akkad was there with his daughter to attend a wedding.

Akkad was born in Aleppo, Syria, in 1930. Syria was at that time under French rule, and so he was a child of empire, with all the ambivalences of identity such experiences inspire. At the age of 19, in 1949, he came to the United States, and studied theater arts at UCLA. He later also did a Master of Arts degree at the University of Southern California. He got his start in Hollywood as a production assistant for Sam Peckinpah on a Western, “Ride the High Country,” in 1962. Peckinpah’s fascination with violence and ambiguity would work itself out in Akkad’s own oeuvre in unexpected ways.

Akkad produced the 1976 film, “The Message,” starring Anthony Quinn, an attempt to tell the story of early Islam to a Western audience. He faced enormous problems as a cinematographer, given that the Arab Muslim tradition is iconoclastic (condemnatory of images), especially with regard to the Prophet Muhammad. Akkad therefore had to find ways of suggesting the Prophet Muhammad’s presence without actually showing him, such as the shadow he cast. But even showing the Prophet’s shadow was denounced by some Muslim groups. The film caused a sensation when its screening provoked the taking of hostages by members of the Nation of Islam, a small African-American sectarian group that is heterodox and had little connection to mainstream Islam. Akkad was confused as to how the Muslim world could not recognize the act of communication he was attempting to perform. As an in-between man, he faced the hostility both of bigotted non-Muslims and of hidebound fundamentalists from his own community. His artistic career played out in the arena of globalizing alienation.

He found it difficult to get funding for the religious films he dreamed of, and in 1978 turned to producing the first of the “Halloween” horror flics. (In this he resembles Richard Gere, who suffers through those romantic comedies so that he can make his serious, Buddhist-inspired ethical films.) The plot of the first Halloween movie had to do with Michael Myers, who as a child of 6 murdered his sister with a butcher knife after she had had sex with her boyfriend. This murder occurred on Halloween. He was institutionalized for 15 years, but then escaped from the sanatarium. He then began to stalk three teenaged girls, even as his psychiatrist and the sheriff attempt to track him down and prevent him from committing further murders.

The anxieties around the Halloween films are, whether it is by coincidence or deliberate, very Middle Eastern. Michael Myers’s killing of his sister echoed the problem of honor killings in the Arab world, where lack of chastity in teenaged girls so dishonors the men of the family that they are sometimes driven to restore their honor by doing away with the girl. (The practice is coded as rural and hotheaded in Arab culture, but its insanity is underlined in the American context.) Myers’s stalking of teenaged girls reproduces that free-floating anxiety about their sexuality and freedom of movement, and the dangers these hold for the masculinity of men. Myers the horror monster is produced through an exaggeration of these anxieties to the point of homicidal rage. Of course, even without any Middle Eastern context, the films are about alienation and the isolation of the individual, a distillation of the neuroses of American suburbia.

Even as he was scaring teenaged couples into hugging tight in American theaters, Akkad was continuing to pursue his dramatic vision. In 1981 he released “The Lion of the Desert,” which centers on the heroic character of the Libyan anti-colonial activist Omar Mukhtar, who fought the Italian empire in his country during the 1920s. Akkad attempted to appeal to Western audiences who might not ordinarily identify with a Muslim populist by configuring him as a rugged individualist fighting Mussolini’s fascist troops. Akkad’s timing was, however, execrable. Only two years after the Iranian Revolution, American audiences just could not establish a connection with Mukhtar’s character. One reviewer (was it in the New York Times?) dismissed the film as “ayatollahs on horseback.” One has the scary apprehension that the Americans actually identified more with the goose-stepping fascists than with the oppressed Libyans.

At the end of his life, Akkad was gathering his energies to do an epic film about Saladin (Salahu’d-Din al-Ayyubi), the medieval Muslim warrior who expelled the European Crusaders from the Middle East. (American audiences were recently reminded of Saladin in the film “Kingdom of Heaven,” which tells the story of the fall of the Crusader kingdom of Jerusalem before Saladin’s armies.) Whether Akkad could have induced Westerners to identify with Saladin remains an open question.

The postmodern two-track film career of Akkad, wherein he attempted to give American audiences horror films about a serial murderer on the one hand, and serious dramas about the Middle Eastern fight against European domination on the other, came to an end in an Amman hotel where both themes melded.

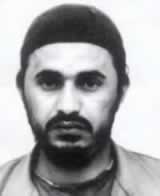

The “Monotheism and Holy War” organization of Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, recently renamed “al-Qaeda in Mesopotamia,” is dedicated to serial murder on a scale that dwarfs Michael Myers’s wildest dreams. The playbook of insurgency requires grisly acts of terror that help to provoke a guerrilla war, which in turn can be transformed into a civil war, destabilizing the old order and paving the way to a coup by the terrorists, who represent themselves as the only force able to restore order. They represent themselves as fighting against American occupation, but the vast majority of their victims are innocent civilians. This horrific form of anti-imperialism targets the innocent relentlessly. Little children are blown to bits, with tiny fingers and feet hurled across public squares from furiously burning ice cream shops.

The guerrilla war in Iraq has claimed a unique cinematic voice of transnational modernity, who had explored the terror of psychopathology and the angst of alienation, as well as the history of anti-colonial movements.

The Iraq conflict has become a bad horror film. It has killed the grandfather of the “Halloween” movies. And it has snuffed out the man who wanted to bring real Muslim heroes such as the Prophet Muhammad, Omar Mukhtar and Saladin to American film-going audiences. Now, his last project will remain unachieved. Saladin was a Kurd from what is now northern Iraq, and he defeated the Crusaders with a legendary chivalry that inspired their respect.

Zarqawi’s henchmen inspire only horror, not respect. They have no chivalry, only bloodthirstiness. They are Michael Myers, not Saladin.

Moustapha Akkad was an American voice as well as a Muslim one. We needed his ability to communicate one culture to the other. His death diminishes us all, and signals the nightfall of a decade-long “Halloween” of the horrific sort for Iraq and for the United States.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved