The four rounds of United Nations Security Council sanctions on Iran are likely about as far as Russia and China are willing to go. Even the new charges against Iran apparently contained in the forthcoming International Atomic Energy Agency report (which do not rise to the level of accusing Tehran of having an active nuclear weapons program or of having diverted uranium to it), according to Reuters, are unlikely to impress China and Russia.

The problem is that sanctions on the Iranian financial and banking sector are already so extensive that the only way to go beyond them is to start a boycott of Iranian petroleum and gas.

But China simply won’t go along with any such policy. In fact, China increased its petroleum imports from Iran in the first half of 2011 by 50% over the previous year. China took 650,000 barrels a day from Iran last June, making the latter the third biggest supplier, following Saudi Arabia and Angola. China also increased its naphtha imports from Iran by 280% over the previous year!

China is now the world’s second-largest petroleum importer, after the United States, and clearly sees imports from Iran as an important part of its energy mix. So China is not voting at the UN to inflict on itself a shortfall of over half a million barrels a day of petroleum

Iran exports about 2.4 million barrels a day of petroleum, of which China imports a little over a fourth.

Moreover, it would not be a good thing for anyone to have a global boycott (essentially a blockade) of Iranian petroleum, since that move would take the 2.4 million barrels a day off the world market and drive prices up to several hundred dollars a barrel.

So it just isn’t going to happen.

(Another significant Iranian export market, India, has been able to pay down its $5 billion in arrears, using the Turkish Halk Bank, and there are rumors that Tehran might turn, or has turned, to a Russian bank as well. India had temporary difficulties in paying for Iranian oil because, at President Obama’s urging, Delhi kicked Iran off the South Asia banking exchange.)

Russia’s Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov recently issued a stern warning against any use of military force against Iran, cleverly reminding Israel and the US that only self-defense or a UNSC resolution could authorize such an attack in international law, and neither is in evidence.

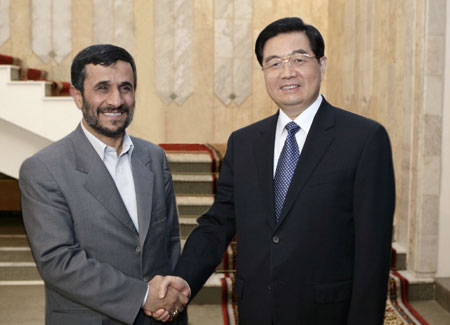

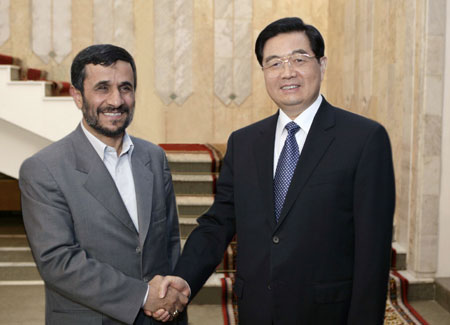

Iranian foreign minister Ali Akbar Salehi attended the summit of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, which groups China and Russia with four Central Asian states. Tehran is seeking to move from observer status to being a full member.

The SCO may prove a congenial home for Iran. It is an area where the US has little diplomatic clout, and the US is seen as bogged down in Afghanistan.

The new, more pro-US International Atomic Energy Agency is willing to speculate about Iran’s nuclear enrichment program in a way that Mohammed Elbaradei never was. I have argued that Iran is seeking “nuclear latency” or the “Japan option,” that is, it does not want to now construct or store a nuclear warhead. Rather, Tehran wants the ability to construct a nuclear warhead in a short period of time if it became necessary to deter an invasion of the sort the US inflicted on Iraq. If Iran actually constructed a nuclear device and detonated it, the action might well produce North Korea-style sanctions and isolation. But latency has almost the same deterrent effect, and is much less costly in global political capital.

© 2026 All Rights Reserved

© 2026 All Rights Reserved