Muslim Brotherhood leader Muhammad Mursi has been officially declared the president of Egypt. But under the terms of the military constitutional guidelines issued last Sunday night, he comes into office in the framework of a military government headed by Field Marshall Hussein Tantawi.

That is, all the doomsaying about Egypt turning into Iran is to say the least premature, since Mursi at the moment is more Tantawi’s vice president than anything else.

Moreover, despite the Orientalist impulse in Western writing to see everything in the Middle East as black and white, as fundamentalist or libertine, Egypt’s political geography has been revealed by this year’s elections to be diverse. It isn’t just puritans versus belly dancers.

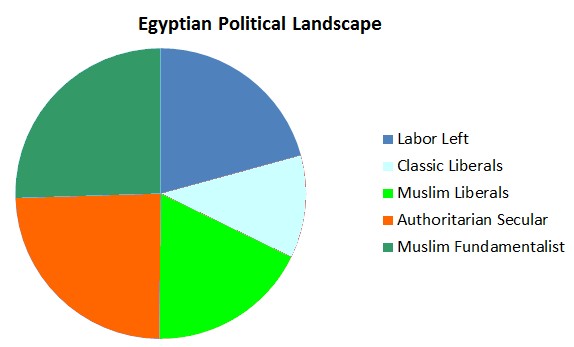

Here are the major factions according to the outcome of the first round of presidential elections, in which there were numerous candidates with strong ideological commitments. I was in Egypt for that election and did a lot of interviewing with Egyptians of all stripes, coming away impressed at how all over the place the electorate was. (Obviously I’m using the candidates below as a sort of political shorthand, and there is more overlap than the categories suggest, but this is ballpark):

1. The Labor Left, led by Hamdeen Sabahi (20.17%)

2. Classic liberals, led by Amr Moussa (11.13%)

3. Authoritarian secularists,led by Ahmad Shafiq (23.66%)

4. Muslim liberals, led by Abdul Moneim Abou’l-Futouh (17.47%)

5. Muslim fundamentalist, led by Muhammad Mursi (24.78%)

Mursi won by retaining the fundamentalists and picking up the Muslim liberals and at least some of the Labor Left, and even a few classic liberals such as novelist Alaa al-Aswani. His victory is not solely a victory for the hard line fundamentalists, who probably only accounted for about half of his voters. He owes the Labor Left and those classic liberals who preferred him to the authoritarian Shafiq.

Mursi will now appoint a prime minister and a cabinet (the Egyptian system is a bit like that of France), and he may well reward his non-fundamentalist allies with key cabinet posts. (That pluralism is exactly what did not happen in Iran after the fall of the Mehdi Bazargan government with the Hostage Crisis of 1979).

Moreover, if in fact Egypt now moves to a new constitution and new parliamentary elections by the end of this year, the more diverse political landscape revealed by the first round of the presidential elections may get reflected in parliament in a way that did not happen in the first election after the revolution. I argue that the Muslim Brotherhood and the Salafi hardline fundamentalists did so well last year because the electorate was still afraid of the Mubaraks returning, and they wanted to put the opposition strongly in power. Now, they’ve soured to some extent on the Brotherhood, and want some law and order and economic initiatives, and may well vote in a significantly different way.

Hamdeen Sabahi is forming a labor left party, and labor flexed its muscles in the first presidential round, given him the major port city and Mediterranean province of Alexandria. Alexandria went to Mursi in this second round, but he can’t count on it in the new parliament.

The strong showing of the liberals and the authoritarian leftovers of the old regime, in provinces of the Delta and key districts of Cairo also suggests that some reformulated National Democratic Party (the old party of Hosni Mubarak) may do well in any new parliamentary elections. Could Ahmad Shafiq end up leader of a powerful bloc in the new parliament?

So not only is Mursi hemmed in by the military, he may well end up having to compromise with a more pluralist political landscape by the end of this year. Whereas he could have gotten legislation through the December, 2011 parliament easily, he may have a more uphill battle in any new parliament.

Admittedly, Mursi is now in the position, as an elected president with a clear popular mandate of about 52 percent of the vote, to maneuver against Tantawi’s constraints. But it remains to be seen whether he can succeed. Mursi on Friday gave a speech in which he rejected the Supreme Court’s dissolution of parliament, which had been dominated by the Muslim Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice Party. The Brotherhood line is that the court had the right to find that a third of the seats, set aside for independents, had been improperly filled by party-backed candidates. But, they say, the executive decision of what exactly to do about that should have been left to the president (e.g. instead of dissolving the whole body of parliament you could have held a do-over for that one-third of seats). Mursi also rejected the military constitutional amendments designed to constrain the president until a new constitution is written.

Among the prerogatives the military claimed was to appoint a new constituent assembly to draft the constitution. But a court-ordered process had already established a constituent assembly, which met over the weekend and insisted they are still in business. Mursi may well back them, setting the stage for one of the first and most important struggles between himself and Tantawi.

Can Mursi force the military to back down on any of these three urgent institutional issues? He certainly can put millions of protesters in the streets if it came to that. But the Brotherhood has a long game, and may well adopt a more piecemeal and less confrontational approach.

One problem for Mursi is in mollifying the half of Egyptians who are absolutely terrified of him, fearing that he wants to turn their fun-loving, moderate country into a puritan, grim, Saudi Arabia. More activist women, Coptic Christians, and the secular-minded middle and upper classes are among these groups. Moreover, the hardline puritan stances he has taken would kill the Egyptian tourism industry (nobody is going on vacation to Sharm El Sheikh and Hurghada to wear their street clothes into the water and be deprived of so much as a beer). There are a lot of powerful economic interests in Egypt that depend on tourism, and on foreign investment. Mursi has to prove he can avoid scaring the horses, or he and his party will crash and burn even without military opposition.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved