By Mohamed Hemish | ( TeleSur | – –

March 25 marks the United Nations’ “International Day of Remembrance of the Victims of Slavery,” which aims to draw attention to the more than 15 million men, women and children who fell victim to the Transatlantic Slave Trade that lasted from the 15th through to the 19th century.

The United Nations calls this 400-year-period “one of the darkest chapters in human history.” And according to the U.N., March 25 is aimed at raising awareness of the dangers of racism and prejudice today.

To mark the day, teleSUR aims to commemorate all victims of the trade but will pay special attention to those who dedicated their lives to ending slavery through resistance and rebellion.

Here are five slaves who fought back and truly changed the world:

1. The Slave Who Defeated Napoleon

Toussaint Louverture was the leader of history’s largest ever slave revolt, which started in 1791 and lasted for over 12 years. The result was the eventual transformation of the French colony of St. Domingue into the independent country of Haiti, the world’s first ever truly anti-colonial, anti-slavery Black republic.

Louverture led the anti-slavery movement in his country into a war for independence, using his political and military genius to fight the French and Spanish colonial powers in what would later become a fully-fledged, independent nation-state.

After winning the war against the French and the Spaniards in 1800, St. Domingue gained autonomy from Napoleon’s French government and Louverture was proclaimed governor of the colony.

The French later launched an offensive to regain control of St. Domingue in 1802 and the Black revolutionary was forced to resign and was deported to France, where he died a year later during imprisonment.

In his absence, his second-in-command Jean-Jacques Dessalines retaliated, eventually leading the Haitian rebellion until its revolutionary completion, finally defeating French forces in 1803.

Haiti became the world’s first colonial society to explicitly reject race as the basis of social ranking, challenging ideas around race and racism in the wider Americas and the long-held belief that white Europeans were inherently superior to their Black counterparts.

2. The Slave Who Documented Her Sexual Abuse, and Changed the Face of North American Minority Literature

Harriet Ann Jacobs was one of the most important female anti-slavery activists in the 19th century, an extraordinary woman who managed to escape slavery and become a prominent abolitionist speaker and reformer.

Jacobs is known for her autobiographical work, "Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl," published in 1861 under the pseudonym Linda Brent.

At a time when the vast majority of slaves were denied the right to education, it was one of the first books to explore the Black female slave’s struggle against sexual harassment and abuse.

Due to the U.S. Civil War, the autobiographical account did not gain recognition until the late 20th century, when interest in minority and women writers exploded due to anti-racist and women’s rights struggles in the U.S. and beyond.

Researchers later identified Harriet Jacobs, who died in 1897 at the age of 84, as the author.

3. The First Black Nominee for US Vice President

Escaping slavery in 1838, Frederick Douglass was an African-American anti-slavery activist, social reformer and intellectual who advocated for equality for all, whether Black, Native American or female.

Douglass was an advocate of inter-racial dialogue and formed alliances as part of the struggle for social justice and the eradication of slavery.

Criticized by fellow activists and abolitionists because he expressed a willing to engage with slaveholders, he famously replied: "I would unite with anybody to do right and with nobody to do wrong."

Douglass went on to become a national leader of the abolitionist movement from Massachusetts and New York until his death in 1895 at the age of 77.

He wrote several autobiographies, describing his experiences and torture as a slave in his 1845 autobiography and bestseller, "Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave."

His last autobiography, "Life and Times of Frederick Douglass," came after the Civil War as Douglass continued his activism for social justice even after slavery was abolished.

Connecting the struggle of Black rights to those of women and other issues, Douglass was active in the women’s suffrage movement. Victoria Woodhull, one of the leaders of the movement, selected Douglass as running mate and nominee for vice president, making him the first African-American in U.S. history to be nominated for the position.

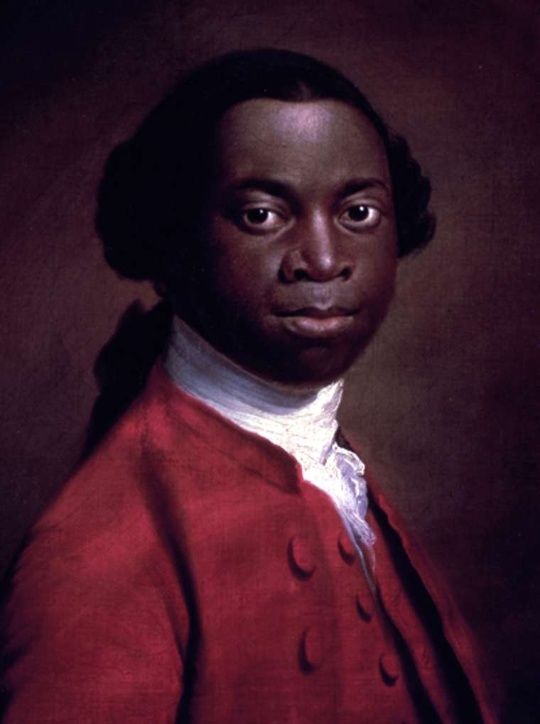

4. ‘The True Beginning of Modern African Literature’

Olaudah Equiano was a prominent African author and abolitionist activist whose autobiography, "The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano," gained widespread attention after it was published in 1789 and was considered influential in the passage of the United Kingdom’s "Slave Trade Act 1807," which officially ended the trade for Britain and its colonies.

In the book he describes the horrors of his time as a slave and how he and his sister were kidnapped from what is now northern Nigeria, shipped across the Atlantic and eventually sold in Virginia, United States.

But Equiano was then sold to famous merchant Robert King, who allowed him to do business on the side and make enough money to buy his own freedom. He went on to travel the world for over 20 years, allegedly taking in places as far and wide as the Arctic, Turkey and the Caribbean.

Since 1967, when a version of his memoir edited by Paul Edwards was released, academic interest in Equiano grew and his work is now regarded as the "true beginning of modern African literature."

5. ‘The First Liberator of the Americas’

Gaspar Yanga, known also as Yanga or Nyanga, was an African leader who led a community of escaped slaves for decades, known as the Maroons, in the highlands near Veracruz, Mexico during the early years of Spanish colonial rule in the 17th century.

Yanga was kidnapped from what is now the Gabonese Republic in Africa, sold into slavery and brought to what is today Mexico. Legend has it that he was a descendant of Gabonese royalty.

In the 1570s, along with dozens of slaves, he escaped and settled in the highlands, isolated and safe from colonial forces. For food and supplies they seized trade caravans that passed by their settlement.

When more and more slaves continued to escape to the Maroon enclave, the Spanish attacked the group in 1609. But Yanga and his people heroically managed to push back against the colonial forces.

In 1618, Yanga and his people reached an agreement with the Spanish and achieved self-rule, with the Yanga family continuing as leaders until Mexico gained its independence in the early 19th century.

In the late 19th century, Yanga was named a "national hero of Mexico" and proclaimed “The First Liberator of the Americas."

The settlement, known as San Lorenzo de los Negros, was renamed after Yanga in 1932. It is not known when Yanga passed away.

Via TeleSur

[Ed. note: See also The British Library exhibit on Ayuba Suleiman Diallo, a Muslim notable from Senegal enslaved in Maryland in the 1700s, who wrote letters back home.]

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved