By Stephen Pascoe | (The Conversation) | – –

To mark the 100th anniversary of the Sykes-Picot Agreement, we’ve got a package with an explanatory article about the secret accord (below) . . .

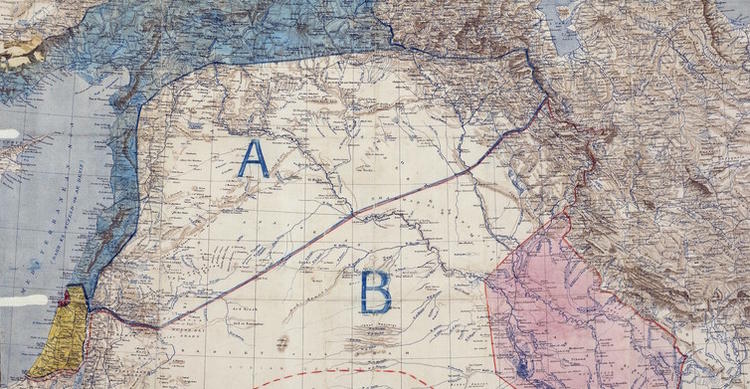

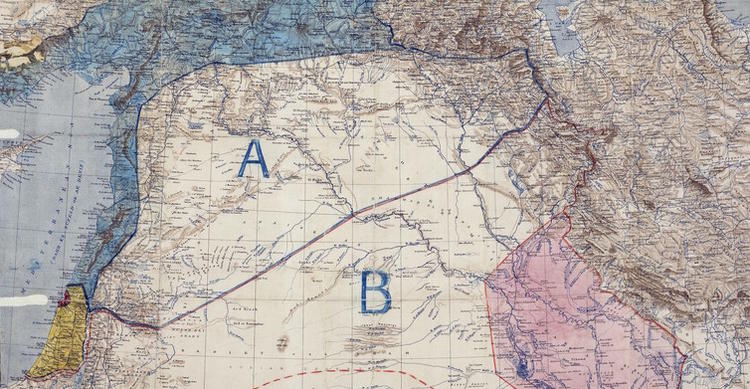

The Sykes-Picot accord was conceived at a high point in Britain and France’s imperial power. Hammered out in the midst of the first world war in anticipation of an Entente victory (the Russian Empire, France and the United Kingdom) over the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria), it was concerned with distributing the territorial spoils of Ottoman defeat.

France and Britain, along with most other European powers, had been convinced of the inevitable demise of the Ottoman Empire for decades. The image of the Ottomans as the “sick man of Europe” was one of the defining images of 19th-century diplomacy.

The accord was also a product of France and Britain’s newfound friendship. In their respective bids for global supremacy during the 1881-1914 Scramble for Africa, the two powers had nearly come to war in the Sudan in 1898, in a military standoff that became known as the Fashoda Incident.

Calmer heads in London and Paris saw that accommodation was preferable to open conflict and sought alliance. The 1902 Entente Cordiale provided for precisely the kind of gentlemanly negotiation over respective “spheres of interest” as embodied in Sykes-Picot.

Dividing the spoils

Both powers had existing interests in the region that they wished to protect and expand.

On the French side, the arms of finance capital were heavily invested in Beirut and Mt Lebanon, alongside a battery of francophone religious and cultural institutions. French railway companies also had substantive interests in the Syrian cities of the interior, as well as in the Cilicia region of southern Anatolia (also known as Asia Minor and now the Republic of Turkey).

In an era when empires were still built on maritime power, the French foreign ministry coveted the coastal strip of the Eastern Mediterranean because of the area’s proximity to France’s North African possessions in Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia.

Britain, for its part, was determined to have its own coastal access – both to the Mediterranean, through the port of Haifa in Palestine, as well as to the Gulf, through Basra in Iraq. The promise of recently explored oilfields also dictated British interest in Mesopotamia (roughly, modern-day Iraq).

France’s original territorial claim extended across to Mosul in northern Iraq, so as to take in some of these promised oilfields.

At the moment Mark Sykes of the British War Office and François Georges-Picot, French consul in Beirut, were negotiating, Commonwealth forces had occupied Basra and the surrounding Shatt Al-Arab region since November 1914. So, the extension of British control northward seemed logical.

Tsarist Russia, the oft-forgotten third signatory to Sykes-Picot, was promised control of Istanbul, the Turkish Straits and the territories of eastern Anatolia.

Royal Geographic Society via Wikimedia Commons

Other contenders

Sykes-Picot should be seen in the context of a series of secret discussions over the postwar political settlement of the Middle East.

On the Entente side, the game of territorial bartering had begun a year earlier, in March-April 1915, as the Gallipoli landing was being planned. The so-called Constantinople Agreement between the three parties rehearsed the divisions that would be formalised in Sykes-Picot.

The Entente powers were not alone in planning for victory. The Ottoman government had itself concluded a secret treaty with Germany upon entering the war in August 1914, dealing with the eventuality of a Central Powers victory.

Ottoman territorial ambitions were far more modest: Istanbul sought the return of three provinces relinquished to the Russians in 1878, along with the territories in the Balkans that had been lost to nationalist secession over the previous decades.

Local leaders were also secretly devising plans for the postwar period. Although the Arab provinces had remained mostly loyal to Istanbul throughout the nationalist turmoil that shook the empire during the 19th century, by the beginning of the 20th there were stirrings for greater autonomy or even secession among certain segments of the Arab military, civilian and religious elite.

Leaders of secret societies in Syria and Iraq, along with the influential Hashemite family of Mecca, which held the position of guardians of the holy cities, had begun in early 1915 to set out a vision of a post-Ottoman Arab state. The Damascus Protocol of May 1915 imagined all of Syria, Iraq and the Gulf – with the exception of the British enclave in Aden – forming an independent Arab state.

In November 1914, the British had began courting the Hashemites in an attempt to orchestrate an Arab revolt against the Ottoman state. In a series of letters exchanged the following year between Sharif Hussein and the high commissioner of Egypt, Henry McMahon, the British appear to give generous – if highly ambiguous – support to the establishment of an Arab state.

Another group with designs on postwar Middle East was the fledgling Zionist movement, which had begun to sponsor Jewish migration to Ottoman Palestine, but remained numerically small on the ground and had as yet no formal support from any major power.

Shifting sands

The notion that Sykes-Picot was a direct blueprint for the post-Ottoman outline of the political map of the Middle East has a seductive simplicity. But it’s not quite the full story.

The nation states of the Middle East we know today were decided on at the 1920 San Remo conference, and their borders were finalised in piecemeal fashion across the following decade.

The shifting territorial claims reflected a number of changing realities in the four years following Sykes-Picot, such as the success of Turkish nationalist troops in reclaiming most of Cilicia under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal, the Ottoman general who led the beleaguered remainder of the empire’s forces to an honourable settlement. He would be dubbed Ataturk, or “father of the Turks”, upon assuming presidency of the new Turkish republic.

Another major shift in realpolitik between 1916 and 1920 was Britain’s position on the Palestine question.

Whereas Sykes-Picot had envisaged an international status given to Jerusalem (in expectation of problems between the nascent Zionist movement and the indigenous Palestinian population, as well as to head off inter-imperialist rivalry over access to the Christian Holy City), the 1917 Balfour Declaration effectively turned the tide of British support toward the Zionists.

When the Ottoman state finally lost control of its Middle Eastern territories – symbolised in the fall of Damascus to Australian troops on October 18, 1918 – control was transferred to Britain’s Hashemite allies, seemingly honouring the undertakings articulated in the Hussein-McMahon correspondence.

Sharif Hussein’s son Faisal seized the opportunity to fill the political vacuum, gathering around him former Ottoman functionaries sympathetic to the Arab nationalist cause. The brief period of Faisal’s Arab Kingdom in Damascus from late 1918 to early 1920 – despite being characterised by significant discord – contained the real hope that the Arabic-speaking populations of the Middle East might at last be masters of their own destiny.

France, unsurprisingly, protested at this turn of events and insisted that Britain honour the principles of Sykes-Picot. Britain acceded to France’s request, Faisal found himself outmanoeuvred and, at a final standoff outside Damascus in the Battle of Maysaloun, his experiment in Arab independence was quashed.

Sykes-Picot had delivered the spoils of war to Britain and France, and deferred the dreams of Arab nationalists.

The accord was arguably the last gasp of unrestrained Western imperialism, or at least of the classical imperialism of the 19th century. Twentieth-century imperialism would take less direct, more pernicious forms.

This article is part of a package marking the 100th anniversary of the Sykes-Picot Agreement. Read the argument that the influence of the accord is overstated or the counter-view that it still underlies the discontent in the Middle East.

Stephen Pascoe, PhD Candidate in History, La Trobe University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved