By Bernadette O’Hare and Stephen Hall | –

Tax abuse is an expensive business. According to a recent report by the Tax Justice Network, avoiding or evading tax deprives governments across the world of around US$427 billion (£302 billion) every year. This is money that could otherwise be spent on things like clean water, sanitation, education and health care.

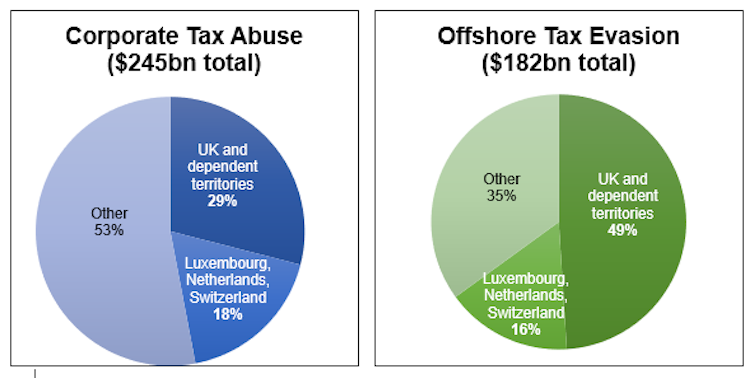

The same report also claims that the laws and practices of just four countries – the UK and its network of overseas territories and crown dependencies, along with Switzerland, the Netherlands and Luxembourg – are responsible for 55% of tax losses suffered around the world.

Now for the first time, we can realistically assess how these huge gaps in tax receipts directly affect the mortality rate of young children and their mothers. We do this using the Government Revenue and Development Estimations (GRADE) tool, which uses government revenue data from the United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research and models the impact of government revenue on child and maternal mortality. Thus we can quantify the human cost of revenue losses through tax avoidance (which is legal) and tax evasion (which is not) for every country in the world.

Unsurprisingly, the biggest impact is felt by the populations of low and middle income countries, when, for example, a multinational corporation under reports their profit to minimise the tax owed locally and instead reports profit in another country with a very low or zero tax rate.

Nigeria, for example, was calculated to have lost almost US$11 billion or US$57 per person in 2020 due to unpaid tax revenue. Projecting this annual loss over a ten-year period, we estimate almost 150,000 child deaths could have been averted if these losses had been curtailed. Imagine the potential for multiple countries and multiple decades.

These kinds of shocking numbers have already had an impact. The Global Legal Action Network, Action Aid and others used them to make a submission to the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC).

Their concern was Ireland’s responsibility for the impacts of cross-border tax abuse which may deprive low-income countries of revenues to spend on children’s economic, social and cultural rights. Following the submission, the UNCRC asked Ireland to explain what it is doing to ensure its policies do not contribute to tax abuse by companies operating in other countries.

The State of Tax Justice 2020, Author provided

This is the first time the UNCRC has examined the consequences of a country’s tax policies on the rights of children living overseas. Hopefully, it is just the beginning. If campaigners elsewhere make similar submissions, the handful of countries responsible for more than half of global tax abuses might be persuaded to review and adjust their approach.

Revenue for rights

Richer countries have a responsibility to the citizens of poorer countries, and this is not limited to ministries concerned with foreign aid. Multinational corporations usually have their headquarters in wealthy countries, which have a moral duty to prevent human rights violations abroad. Governments must not remain passive when organisations based within their territory harm such rights in other countries.

This is especially crucial for low and middle income countries, but equally, the governments of those countries must seek to protect their citizens and prioritise fundamental rights over business interests.

In the future, multinational businesses ought to be required to publish profits and tax paid in the country where the profit and tax was generated. Fortunately, momentum is gathering behind requiring this kind of public reporting. Increasingly companies appear to be publishing this information voluntarily – one example is Vodafone.

When this data is available – from both corporations and countries – the GRADE tool can be used to shine a light both on the positive impact these taxes have on lives, and the negative effects of lost revenue. We hope it could become a powerful weapon in the battle for transparency and a move away from the kind of practices which compromise fundamental human rights.![]()

Bernadette O’Hare, Senior Lecture in Global Health Implementation, University of St Andrews; Kyle McNabb, Research Associate, Overseas Development Institute, and Stephen Hall, Professor of Economics, University of Leicester

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Featured Illustration: A colored Emoji from emojione project

Date 3 December 2016

Source https://github.com/emojione/emojione/tree/2.2.7

Creative Commons license

© 2026 All Rights Reserved

© 2026 All Rights Reserved