The big news out of Iraq over the weekend was the awarding of a handful of new oil development contracts to companies such as Royal Dutch Shell and Russia’s Lukoil. These bids follow earlier awards of fields for development to China. The American oil majors failed to conclude any new deals, though Exxon Mobil won a bid for West Qurna 1 in November. The Iraqi authorities have strong motivations to diversify their petroleum customer base given the current hegemonic position of the United States in their country.

It should be noted that one of the likely aspects of increased petroleum exports in Iraq will be to strengthen the central government’s ability to provide order, to arm and equip its police and the 275,000 or so men in the Iraqi military. This effect of greater petroleum resources is likely to come too late to have much effect on President Obama’s withdrawal plans. There is much speculation among observers over other possible effects of these oil deals. The Iraqi government is eager to highlight them as a sign of growing Iraqi self-confidence and reintegration into the world economy. Others focus on the impact on oil prices were Iraq to expand its production from 2.5 mn b/d to 4.5 mn b/d. Others speculate that increased production would allow Iraq greater autonomy from Iran. Still others suggest the dominant position of Saudi Arabia as a swing producer could be undercut by the emergence of a big new player.

In my view, these developments are unlikely to have nearly as great an impact as is often suggested, nor is the increase in production likely to come very soon. Many analysts neglect to take into account the single most important cause for the sea change in petroleum markets, which is rapidly increasing demand from China, India, and other Asian powerhouses. Rupert Murdoch famously predicted that the overthrow of Saddam and the bringing back online of Iraqi petroleum would produce $20 a barrel oil. As I write, Mr. Murdoch was off by $50 dollars a barrel at the very least. China’s petroleum consumption was up by 14% this November over the previous year, and daily imports have risen now to over 4 million bpd. Not so long ago, China was bringing in just 3 million bpd. In other words, even if Iraq could suddenly increase its production by a million barrels a day, it would simply be meeting the recent increase in Chinese demand. The extra petroleum Iraq might pump in the near to medium term won’t keep oil prices low, it will simply help prevent them from skyrocketing.

Moreover, signing a bid and actually developing a new field and exporting the petroleum are not the same things. Iraq’s security situation will make it difficult for foreign companies to make quick strides in this regard. As the FT article noted, there still is no federal petroleum law in the absence of which many companies will be reluctant to go forward. Iraq’s civil bureaucracy, including the Ministry of Petroleum, is in shambles, and in the near to medium term will prove an inadequate partner to these high-powered global petroleum concerns. It is not even clear who will be in control of Iraq a year from now, that is to say, who will be interpreting the contracts just signed. In the foreseeable future, Saudi Arabia remains the swing producer.

Nor would an influx of extra petroleum wealth necessarily cause friction between Iraq and Iran. The major Shi’ite parties that now control Baghdad have strong ties of friendship, support, and to some extent ideology with Tehran. Indeed, the rise of a wealthier, Shi’ite-ruled Iraq is almost certainly good news for Hizbullah in South Lebanon since the ruling Dawa Party helped to form Hizbullah in the first place, and it is likely that newly wealthy Iraqi Shi’ites will bestow patronage on Sheikh Nasrallah, reinforcing Tehran’s own support. That is, an oil-rich Shi’ite ruled Iraq alongside the Khomeinist regime in Tehran portends a vast increase in the power and influence of Shi’ite movements, a development that strengthens Iran rather than detracting from its position.

The petroleum wealth, insofar as it flows into government coffers, will also prove challenging to the survival of Iraqi democracy. Very few countries that generate more than 25% of their GDP from petroleum exports have managed to remain stable and democratic. It is simply the case that petroleum wealth will, over time, make the Iraqi government overwhelmingly powerful vis-à-vis its own citizens. Charges are already flying that Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki is using his control of petroleum resources to establish tribal militias loyal to his Dawa Party, and to bolster Dawa’s performance in elections.

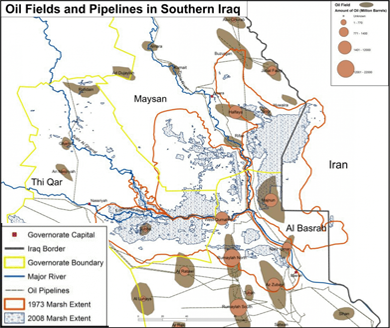

Courtesy iraqimarshlands.org

For more on Iraqi petroleum, see Iraq Oil Report.

A tendency towards a return to strongman rule in Iraq has been seen by some critics as exemplified in new, draconian press censorship codes which critics maintain may well hobble Iraqi journalism. See also this Al Jazeera report on restrictions on the importation of books and other censorship practices, which provoked a recent demonstration in Baghdad:

End/ (Not Continued)

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved