Barin Kayaoğlu writes in a guest column for Informed Comment:

AKP and “Back to the Future” Turkish-Style

[For the Turkish version of this post, click here.]

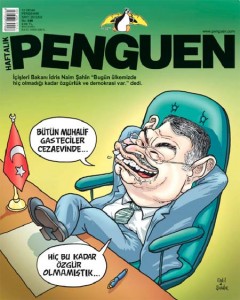

The NGO Reporters Without Borders has demoted Turkey by 10 places in its World Press Freedom Index rankings for 2011-2012. The report’s statement that “the judicial system launched a wave of arrests of journalists that was without precedent since the military dictatorship [of the early 1980s]” reminded me of the “Back to the Future” movie series.

In the trilogy, the heroes use a time machine to go back and forth between the past and the future, which causes them to inadvertently change events and cause new problems. As Turkey tries to solve its old problems with outdated means, it faces the same contradiction as the heroes of “Back to the Future”: without learning from the mistakes of its past, Turkey seems destined to repeating them.

Most of the blame for that problem lies with Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP in Turkish). Just as the AKP deserves credit for the economic boom of the past 10 years, it is also responsible for the recent decline in democratic standards in Turkey. Especially under the counter-terrorism law of 2006, an increasing number of journalists and college students have been detained on terrorism-related charges, which include writing books that have not been published or reading others that are readily available in bookstores.

The point is not to berate the AKP. That is too easy and it is done elsewhere. The real question is why the AKP is turning to despotism at a moment when it tries to promote Turkey as a “model” in the Middle East?

The AKP’s authoritarianism rests on two possibilities:

– As Turkey’s prospects for joining the European Union decrease, AKP’s reformist reflexes have weakened.

– Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his cadres have a background in political Islam, which emphasizes a “culture of obedience.” Therefore, they never really had a reformist agenda.

Although both arguments have an element of truth, they fail to explain the full picture. For example, if EU countries’ reluctance to admit Turkey as a member had been the real cause for the AKP’s authoritarianism, most European politicians had opposed Turkish membership before Ankara had initiated accession negotiations with Brussels in 2005. In other words, Turkey’s chances for membership were quite small from the start. Nevertheless, AKP’s reforms, especially on the use of Kurdish in public, allowed the accession negotiations to commence. Despite the Eurozone crisis, AKP still insists that it is adamant about joining the European club. As such, to tie AKP’s increasing authoritarianism to the problems with EU membership is insufficient.

The second point is moot for similar reasons. If the AKP had never been genuine about its commitment to reform, it would not have bothered with the EU membership process so much. Moreover, if the “culture of obedience” is the paramount dynamic for political Islamists in Turkey, there would not have been a party called AKP today because Mr. Erdoğan and his friends could not have revolted against the leading traditionalists of the Virtue Party in 2001. At any rate, if a sense of obedience had been that strong among Turkish Islamists, three political parties with Islamist tendencies would not have existed in Turkey today (AKP, HAS, Saadet). “Obedience” is important for religious conservatives in Turkey but it is insufficient in explaining the current situation.

Which brings us “back to the future”: the state’s continuing predominant role in economic life and an insecure neighborhood makes authoritarian methods enticing for the AKP. The same is true for the party’s supporters in the media. In fact, many newspapers that supported the “soft coup” of 28 February 1997 (known for the date when the Turkish military gave a stern warning to Prime Minister Necmettin Erbakan for his Islamist leanings, causing him to resign less than four months later) back the AKP today. Sabah newspaper, which supported the “28 February process” in 1997, today supports the AKP for similar reasons. It is owned by a business conglomerate that is close to the AKP. Sabah’s previous owners had been allied with hardline secularists.

Zaman newspaper is an even better example. Despite being part of the religiously conservative Fethullah Gülen movement, Zaman had also lent support to the military in 1997 (though not as overtly as secularist papers). Today, it is virtually the AKP’s mouthpiece and pretends to condemn the Turkish military’s role in politics.

The journalist Fatih Altaylı is another notable example. Mr. Altaylı had directed the most powerful criticism as a columnist against Mr. Erbakan in 1997 but today he is using his Habertürk newspaper to support Mr. Erdoğan.

The most important reason for the media’s support for the AKP is that large corporations with media interests do not wish to alienate the ruling party by raising their voice. No conglomerate likes to idea of losing a lucrative government contract because of its media outlet’s reporting. It is for that reason that mainstream media outlets do not investigate allegations and arrests under the ongoing “Ergenekon” and “KCK” cases. (“Ergenekon” refers to a network of army officers and their supporters who allegedly tried to carry out a coup in 2005 and 2007 while “KCK” is the alleged political wing of the Kurdish group PKK, which is designated as a terrorist organization by Turkey, the United States, and the European Union.)

To be sure, auto-censor is not the only problem. Methods other than arrest are equally useful. Last summer, influential journalists Can Dündar, Ruşen Çakır, Banu Güven and Nuray Mert “left” the leading news network NTV while the columnist Ece Temelkuran was metaphorically thrown out of Habertürk in early January. All five were opposed to the AKP. The episodes bring memories of the military’s treatment of the journalists Mehmet Ali Birand and Cengiz Çandar in the aftermath of the 28 February coup.

The AKP’s stated aim is to not to take Turkey “back to the future.” Quite the contrary: it promotes Turkey as a viable “model” that combines democracy and free market capitalism to other countries in the region.

But Turkey could serve as a model only if it could consolidate a genuinely democratic regime. At the moment, most Middle Eastern countries already share the bottom of the World Press Freedom Index with Turkey. Unless the AKP remembers the dynamics that brought it to power in 2002 – authoritarianism, corruption, restrictions on the media (all products of 28 February) – it runs the risk of joining the parties that it defeated ten years ago in oblivion.

—

Barın Kayaoğlu is a Ph.D. candidate in history at The University of Virginia He is currently writing his dissertation on U.S. relations with Turkey and Iran during the Cold War and the origins of anti-Americanism in the two countries. This post was originally published in Turkish.

© 2026 All Rights Reserved

© 2026 All Rights Reserved