The destabilization of Mali and southern Algeria is a complex political and social process that does not have only one cause. But a changing ecology forced by climate change is a major contributor to the region’s problems.

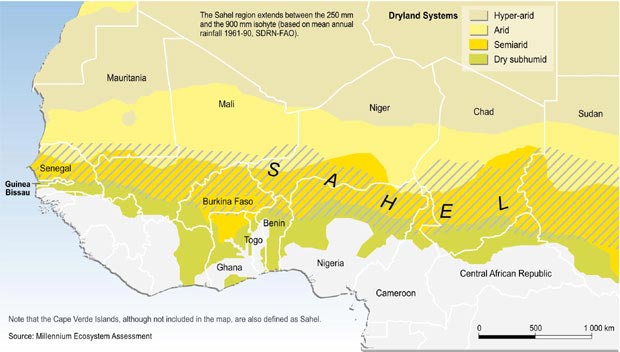

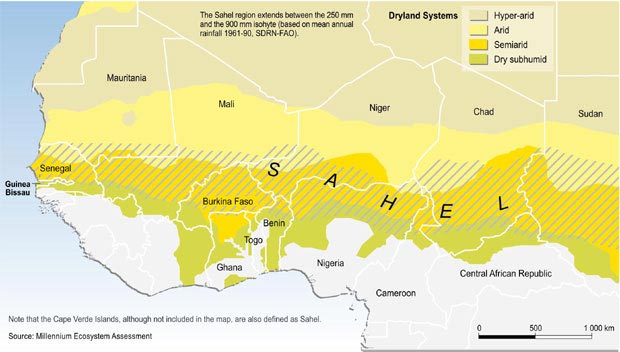

This region is part of a Saharan and sub-Saharan band across Africa called the Sahel. I have traveled a bit in the far west of the Sahel, in rural Senegal.

h/t Robert Stewart

The climate of the Sahel has fluctuated over the decades, being determined by big phenomena such as El Nino and the Indian Ocean monsoon, as well, it has been discovered, as how warm the waters of the Indian Ocean are. In the first 7 decades of the twentieth century, the region got a fair amount of rainfall, and lower Mali where the capital of Bamako is could raise livestock, making Malians agriculturally relatively well off. The consequent rise in population (Mali is now about 15 million) probably made the country overpopulated for what it could sustain in the more arid decades after 1980, when the warming waters of the Indian Ocean produced dry conditions in the Sahel.

Global warming has accelerated in the past 40 years, as the billions of metric tons of carbon dioxide factories have spewed into the atmosphere has produced a greenhouse effect, trapping heat in the earth’s atmosphere.

The drought of the 1970s caused thousands of northern Mali Tuaregs to go to Libya. Col. Muammar Qaddafi organized them as a mercenary unit. Qaddafi, however, dissolved it in the late 1980s, at which time many Tuareg came back to Mali and participated in the 1990 coup.

Al-Sharq al-Awsat, Jan. 12, 2013, explains (trans. USG Open Source Center):

“… Iyad Ag Ghali was born in the Kidal Region of northern Mali. He hails from the Ifoghas Family, a noble Tuareg family. The northern region, at that time, was prosperous owing to livestock development; however, it later suffered a severe drought which destroyed life in the region and made the residents migrate to distant countries, reaching Chad and Libya. (Late Libyan Leader)

Libyan dictator Mu’ammar al-Qadhafi took advantage of the Tuareg migration from northern (Mali) and established an independent Tuareg army that he called the “Islamic Legion” (also known as the Islamic Pan-African Legion). Iyad Ag Ghali joined this legion in early 1980s and showed tremendous courage. This prompted Al-Qadhafi to send him to Lebanon to fight against the Christian phalangists there. He also took part in the Chad war before returning to Mali as Al-Qadhafi announced the dissolution of the Islamic Legion. However, the moment he returned to Mali, he contributed to the 1990 military rebellion and became one of the outstanding leaders of the rebellion movement. It was he who led the final attack of the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA) against the Malian forces in Manaka City on 28 June 1990.”

Ghali was active in the secular Tuareg nationalist movement, National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA), in northern Mali in the 1990s.

Then in the late 1990s, he came into contact with the Tablighi Jama’at, a Pakistan-based Muslim revivalist organization that specializes in helping secularized Muslims recover their faith. Tablighi Jama’at is politically quietist and not violent, but is relatively fundamentalist with regard to approach to Islam. Ghali became fanatically religious and gradually adopted Wahhabi ideas, becoming devoted to destroying the Sufi shrines so popular in Mali.

Al-Sharq al-Awsat explains (trans USG OSC):

“When the rebellion movement broke out once again in northern Mali in 2006, former (Malian) President (Amadou) Toumani Toure assigned him the task of negotiating with the Tuareg. In August 2006, the negotiations resulted in the Algiers Accords. In 2007, the president appointed him as a consular adviser in Jedda, Saudi Arabia. However, in 2010, he returned after suspicions arose about his affiliation with Al-Qa’ida Organization. Having been deported to his country of origin, he reassumed his previous role as a mediator in releasing hostages; he had become wealthy by then. In 2011, he separated himself from the MNLA, established the “Ansar al-Din,” and, in alliance with jihadist movements, he became in control on the ground. In his first military move since he changed intellectual and ideological convictions, Iyad (Ag) Ghali attacked the city of Aguelhok in far northern Mali and took over a fortified military base of the army there.”

Ansar Dine, Ghali’s organization, doesn’t seem to me to have grown out of the 2011 Libyan War and return of Tuareg mercenaries from Libya. Ghali came back from Libya in the late 1980s, and his turn to radical Muslim fundamentalism happened in Mali in the late 1990s under Pakistani influence.

The return in 2011 of further mercenaries did contribute to the declaration of Azawad independence by the Berbers of the north by the secular nationalist Azawad National Liberation Movement. Its members don’t for the most part agree with Ghali’s harsh Wahhabi ideas.

In turn, the loss of territory in the north angered the Mali officer corps and contributed to their decision to make a coup against elected president Amadou Toumani Touré last March. The sanctions slapped on Mali as a result by its neighbors and by NATO members later last year forced the military to at least say that they were abadoning the coup, installing the speaker of parliament, Dioncounda Traoré and a national unity cabinet. This government was in turn overthrown by the officers in December, 2012, so that there has been a second coup.

The weakness of the Mali government likely is related to the drought years of the past decade, during which hundreds of thousands of Malians were forced to emigrate to other countries and the agricultural productivity and tax base of the more fertile south was devastated. This economic decline at the center made it easier for the rebel Tuareg of the north to declare their Azawad. There are several factions in the north, some of them Berber-nationalist and relatively secular, but the best fighters seem to be Ghali’s Ansar Dine, and their movement south last Thursday helped provoke the French intervention. The harsh drought conditions may or may not have contributed to the radicalization of sections of Mali’s Muslim population, though of course that the radicalization took the form of radical fundamentalism is an accident of history (in the Cold War period they likely would have turned Communist)

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved