140 nations meeting in Geneva have concluded an accord to limit mercury emissions, which must now be ratified by individual nations. It has implications for coal-fired power plants, among the most serious contributors to mercury pollution, as well as cement factories The treaty also seeks an end to mercury use in thermometers and batteries, and limitations on the transport of gadgets containing it. It put off a decision about artisanal gold mining, where the metal is deployed in small scale operations.

But coal is the most important villain here.

Mercury is a nerve poison and causes neurological and brain problems, as well as damaging the heart and kidneys. It is far more prevalent in the human environment, especially in water and fish, than before the industrial revolution. The UN has been discussing this issue for some time. Progress had been blocked by the Bush administration (sometimes you forget for a second how evil they were), but Barack Obama’s election in 2009 allowed the negotiations to proceed.

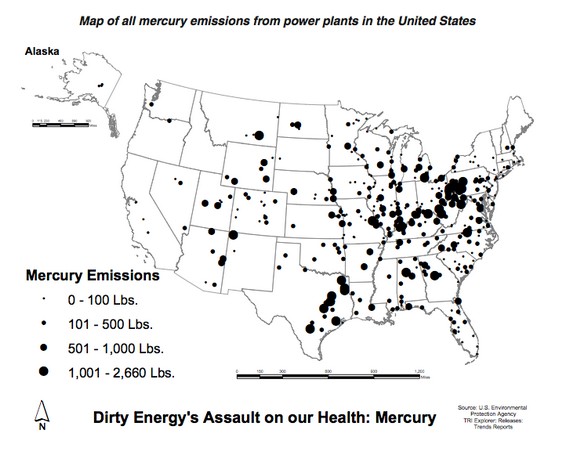

Coal provides over a third of US electricity now, down from 42% in 2011. The Environmental Protection Agency has to its credit begun insisting on filters to prevent mercury emissions at US coal plants, imposing costs that have caused many of them to close down. They can’t compete with increasingly inexpensive natural gas and wind if they have to invest billions to avoid poisoning us.

Unfortunately, the closing of the coal plants is not happening fast enough, and 1.4 gigawatts of new coal-fired power was installed in 2012. Coal is a major contributor to carbon dioxide emissions and disastrous climate change, in addition to the mercury problem.

I noted last Monday,

“The United Nations Environmental Program has just issued its [pdf] 2013 assessment of the mercury threat.

It finds that human-caused

“emissions and releases have doubled the amount of mercury in the top 100 meters [yards] of the world’s oceans in the last 100 years. Concentrations in deeper waters have increased by only 10-25%, because of the slow transfer of mercury from surface waters into the deep oceans. In some species of Arctic marine animals, mercury content has increased by 12 times on average since the pre-industrial period. This increase implies that, on average, over 90% of the mercury in these marine animals today comes from anthropogenic [human] sources.”

‘

© 2026 All Rights Reserved

© 2026 All Rights Reserved