Pakistan, a country 97 percent Muslim, has just made its first successful transition from one elected, civilian government to another since its founding in 1947. The country has had long bouts of military rule, and a history of coups against elected prime ministers, as well as, in the 1990s, a series of presidential decrees dismissing governments before their term was up (a prerogative the president no longer has). In 1999, Gen. Pervez Musharraf made a coup against then Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, sending him into exile in Saudi Arabia. Today, Sharif is on the cusp of forming a new government, and Musharraf has just had to post bail in a criminal case against him.

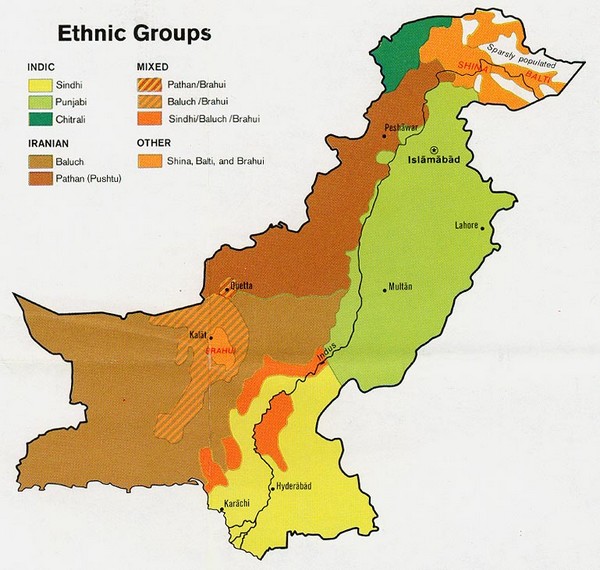

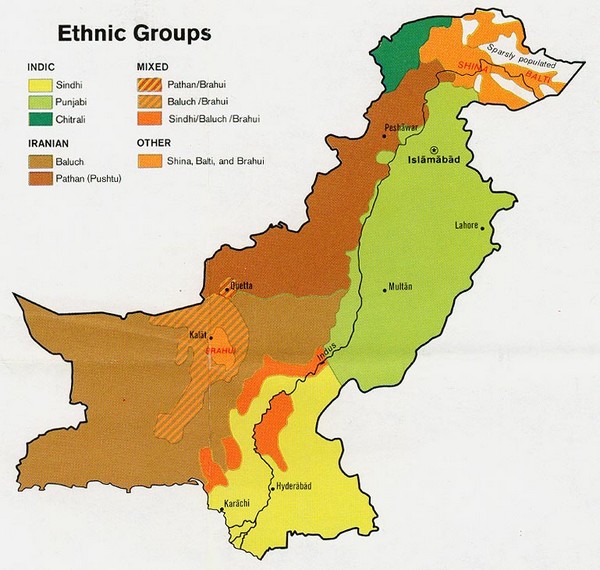

The election in Pakistan had some difficulties, and one international observer termed it only 90% upright, 10% corrupt. In particular, the large port city of Karachi has seen a lot of contention about the outcome, and a prominent politician there was assassinated. Still, the over-all outcome of the election appears to be on the up and up. People really were tired of the largely corrupt Pakistan People’s Party, which had difficulty delivering basic services like electricity and water. The major opposition party organized to win at the polls, the Muslim League, has emerged as the single largest party, and has attracted enough independents to cross the aisle that it can form a government without going into coalition. The Pakistan Justice Movement (PTI) of Imran Khan made an amazing showing as a set of fresh faces, and became the third largest party. It will form the provincial government in Khyber Pukhtunkhwa (the old North-West Frontier Province), the Pushtun-majority area that has been bedeviled by Taliban extremism, and where voters prefer secular alternatives.

The emergence of Imran Khan’s PTI as a third force in Pakistani politics, standing, it says for human and women’s rights, is an important indicator of change. Likewise, the Pakistani judiciary and rule of law has begun playing a more forceful role in the country’s politics since 2008. The army seems happy enough to be back in the barracks and is focused on its contest with India in Kashmir and Afghanistan.

A persistent meme in punditry, which sometimes has found echoes in academic literature, saw Islam as inimical to parliamentary democracy. It was always a stupid argument. Arguably, Islam per se has seldom been very important in Pakistani politics, which like all politics are primarily about competition for state resources among large socio-economic groups. The small fundamentalist Jama’at-i Islami has never done very well in elections, and did not do well in this one. Aside from 1970 and 2002, it has seldom broken above 3% of seats in the federal parliament, and only once been a dominant force at the provincial level (it was part of a ruling coalition in the North-West Frontier Province in 2002=2008). Pakistan had difficulties with democracy in part because of the way the 1947 Partition from India worked out. West Pakistan had virtually no industry, was largely rural, and cities like Lahore were hurt by the departure of Hindu and Sikh mercantile classes. It inherited a lion’s share of the old British Indian Army (the British had categorized Muslim Punjabis as a ‘martial class,’ good at fighting). So you had a country of officers, hacienda landlords, and peasants, and it wasn’t a recipe for democracy (as the similar social profile in much of Latin America in the 1950s and 1960s also was not).

Ironically, some of the punditry about Islam being incapable of democracy was generated by the Israel lobbies, which wanted to position Israel as a democratic ally of the US and similar to it, and to castigate the Muslims as prone to dictatorship and aligned with whatever the enemy du jour of the US was– Communism, Third Worldism, al-Qaeda– it didn’t seem to matter. It is ironic because there are real issues in Israeli, Zionist democracy, which treats non-Jews as second class citizens and privileges groups like the Ultra-Orthodox, not to mention ruling undemocratically over millions of stateless, Occupied Palestinians.

But Pakistanis have many roles and identities beyond their religion, and those roles can change rapidly. The Pakistan urban middle classes have grown by leaps and bounds since 2000, and they are enthusiastic about parliamentary politics. The proportion of people living in cities is now 36% , and if you include the rurban population (many villages around Lahore, e.g., are now integrated economically with the city), people living in the orbit of urban life are likely a majority.

The two big storied parties in Pakistan have been the Pakistan People’s Party, which just lost big, and the Muslim League. The PPP began as a populist party, analogous to the US Democratic Party before 1965, putting together a coalition of urban workers and southern (Sindhi) rural landlords and peasants, and it had a rhetoric of secularism and left of center ideology. It won the 2008 elections but has governed very badly, and was punished at the polls.

The Muslim League began as a vehicle of Muslim representation and then separatism in the old British India before 1947. After 1947 it picked up various constituencies, including Punjabi landlords and many of their peasants (thus succeeding the old Unionist Party of the colonial era), as well as shopkeepers and the budding class of business entrepreneurs. Hence, the party’s current leader and the new prime minister, Nawaz Sharif, is a steel magnate. The party favors private enterprise and more open markets. Roughly speaking, the Muslim League has some resemblances to the US Republican Party. Despite the “Muslim” in its name, the party is not notably fundamentalist in orientation, though its deputies have been willing to pass legislation strengthening the hold of Islamic law (just as a lot of American Republicans are not themselves pious but are willing to pass laws restricting abortion to get the evangelical vote). George W. Bush, during the 2007-2008 transition from military rule, tried to campaign against the Muslim League, confusing it apparently with the Jama’at-i Islami or even al-Qaeda!

All religions have had difficulties coming to terms with Enlightenment ideas, but religion has seldom been determinative in the formation of modern nation-states. Is Austria less democratic because majority Roman Catholic? Yet in the mid-19th century the pope condemned most democratic practices as a modernist heresy, and at some points forbade the faithful to vote in elections. An argument was also sometimes made that Confucian societies had difficulty with democracy, hence Japanese, Korean and Taiwanese militarism and the Chinese one-party state.

Such culturalist arguments always flounder in the end because culture itself is fluid and changing. Once Japan, then South Korea, then Taiwan, underwent democratic transitions, the old Confucianist argument fell by the wayside. Likewise, the argument about Islam being incompatible democracy seems increasingly threadbare.

What happens in Pakistan matters to the rest of the world. Pakistan is the world’s sixth most populous country, with some 176 million people (after China, India, the United States Indonesia and Brazil). It is the world’s 46th largest economy, trailing Egypt and the Philippines, even though its population is much greater. It is a nuclear state, like the US, Russia, France, Britain, China, Israel and India. Keeping its parliamentary democracy going will require that Pakistan develop economically.

Cole’s Laws of Economic development are that 1. Poor countries must grow 6% faster than their populations for many years in a row to raise per capita income; 2. Poor countries must wring corruption out of their governmental system; 3. Poor countries must invest in infrastructure, including electricity (you can’t run factories during blackouts) and security; 4. Poor countries must make things others want to buy at an attractive price and quality; 5. The rich in poor countries must be made to pay their taxes and 6. Poor countries must attract foreign investment because local business elites are small and weak.

Islam seems to me largely irrelevant to these sorts of policy. Saudi Arabia manages to attract a lot of foreign investment despite being a fundamentalist Wahhabi state far to the right of Pakistan (which has a lot of Sufis, urbane Shiites and secularists).

Pakistan under the Pakistan People’s Party was doing the opposite of these six things. Pakistani population growth rates are high, and its economy has only been growing 3% a year, which means virtually zero per person increase. The infrastructure has been neglected, and the shortfall in electricity production is an astounding 40%. The PPP, though not only it, is extremely corrupt. Only 25 percent of the economy is taxed.

The good thing about Nawaz Sharif being prime minister is that he is a businessman and understands some of these issues. He lowered barriers to trade in the 1990s. But with regard to development, Pakistan has been going in altogether the wrong directions. It needs to find ways of growing the economy faster than it is growing its population. Turning it around so that it avoids social and economic deterioration will be no easy task.

I doubt any of it has much to do with Islam one way or another.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved