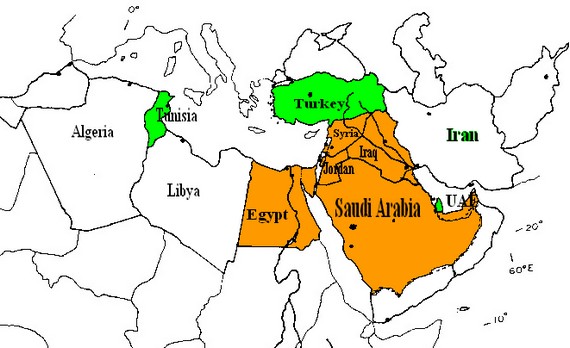

The change of government in Egypt produced starkly different reactions in various Middle Eastern countries, which tells us something about the situation there.

With the exception of maverick member Qatar, the Gulf Cooperation Council, grouping six conservative Gulf oil monarchies, cheered loudest for the military coup made by Brig. Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Sisi against elected President Muhammad Morsi of the Muslim Brotherhood (provoked by a mass movement against Morsi). Even Qatar reacted correctly, congratulating the interim appointed president, Adly Mansour, on his new office. Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Kuwait went much further in warmly welcoming the change in government, with Saudi Arabia’s King Abdullah being the first Arab ruler to weigh in. Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Kuwait were so enthused that they offered altogether on the order of $9 billion in aid to the new government. Qatar had given billions to the Muslim Brotherhood government of Morsi.

Since political Islam is an important underpinning of some of the GCC states, you would think they might have been happy about the rise of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt. Save for Qatar, they weren’t. Saudi Arabia has long had a love-hate relationship with the Brotherhood. Since 9/11, they have been suspicious of it as a radicalizing force in the region (ironic because people say the same thing about their Wahhabi, fundamentalist form of Islam). Perhaps more important, the Saudi regime views Egypt as its strategic depth, seeing the Egyptian military as providing a crucial security umbrella. Deposed President Morsi’s willingness to establish diplomatic ties with Iran alarmed the Saudis, and they did not like Morsi’s rather open alliance with Qatar, Saudia’s rival.

The United Arab Emirates is only 18% Arab with regard to residents as opposed to citizens, and even that 18% is afraid of the Muslim Brotherhood, which in the UAE is viewed as a dangerous cult. The Brotherhood, as a fundamentalist organization, challenges the tribal ties of UAE society and the charisma of its leaders is an unwelcome rival to the authority of the emirs. Brotherhood members in the UAE were recently tried on conspiracy charges. Likewise, the emir of Kuwait sees the Kuwaiti Muslim Brotherhood as rivals for authority and the Kuwaiti government and the press supportive of it are obviously pleased at Morsi’s removal.

Basically, the Gulf Cooperation Council is happy about a reversal in Brotherhood fortunes because it is seen as a republican, revolutionary and cult-like group. The emirs mostly don’t like it. And the GCC, made up of small weak and very wealthy states, is happier with the Egyptian military in a commanding position, since they see it as their own night watchman.

Unsurprisingly, Jordan, a pro-Western Sunni monarchy with along history of domestic conflict with Jordan’s small Muslim Brotherhood, was supportive of the change in Egypt. Jordan has applied to join the GCC, and provides security services to them, and they provide aid to Amman.

But what is amazing is that Iraq and Syria, who are in conflict with the GCC, also were positive toward the events in Egypt. Iraq’s Shiite prime minister Nouri al-Maliki promptly sent congratulations to interim President Adly Mansour. A member of Nouri’s party said, “The reason behind the downfall of Morsi is that he became subject to the control of the Salafists. This proves that the Arab street rejects extremist religious rule.” The Shiite government of Iraq faces opposition from hard line Sunnis, and so was happy to see the back of Morsi. But what is ironic is that al-Maliki’s own Islamic Call (Da’wa) Party is a manifestation of political Islam and is center-right. The Sunni-Shiite divide in Iraq is coloring Baghdad’s reception of these events.

The Baath government of Syria, which the GCC is trying to overthrow, was also happy about the uprising in Egypt. Syria’s secular government faces an uprising on the part of its own Muslim Brotherhood (though the anti-government sentiment is widespread among Syria’s secular Sunnis and Sufis, as well). Morsi, after angering the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood by being coy about that country for months, finally called for a no-fly zone over that country. So Bashar al-Assad is having some Schadenfreude right about now; he is still there, and Morsi is gone.

Iran hasn’t taken a strong stand. Tehran was happy about Morsi’s overtures on opening an embassy, but Iran’s Shiite ayatollahs are suspicious of Sunni Muslim fundamentalism. That Egyptian Shiites had been recently lynched, and Morsi had not spoken out forcefully against the horrible murders, didn’t endear him to Tehran. Some Iranian intellectuals denounced the idea of a military coup. But many felt that Morsi had over-reached and been too hard line. (You wonder if their criticism of Morsi is code for criticism of Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei).

On the other side of the ledger, Turkey has been a vocal critic of the change in Cairo, in fact Prime Minister Tayyip Erdogan has denounced the “putschists” in Cairo and called for the immediate release of Dr. Morsi. Erdogan leads a modern political party of the center-right, slightly tinged with Muslim themes, and Turkey in general has suffered from numerous military coups. Turkey has been conducting vigorous diplomacy at the European Union and elsewhere against the legitimacy of the Adly Mansour government.

Tunisia’s democratically elected, center-right Muslim religious government, headed by PM Ali Larayyedh, also expressed dismay at Morsi’s overthrow. The Renaissance or al-Nahdah Party sees Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Sisi as way too much like Gen. Zine el Din Ben Ali, who had come to power in a coup in 1987, and whom the Tunisians overthrew in the name of democracy in 2011. Some Tunisian secularists have begun speaking of starting their own Rebellion or Tamarrud movement against the fundamentalist Renaissance Party, which has disturbed the government. Even the secular President, long-time human rights activist Moncef Marzouki, denounced the coup in Cairo.

Algeria, whose government is secular and is suspicious of Muslim religious groups in politics, did not send congratulations to President Mansour and expressed hopes Egypt would return quickly to stability. Algeria’s government in late 1991 cancelled the electoral victory of a Muslim fundamentalist party, throwing the country into years of bloody civil war. Algiers doesn’t think al-Sisi knows what he is getting himself into.

Israel must be pleased, having good relations with the military and being very suspicious of Morsi and the Brotherhood. But they haven’t said much publicly. But the secular PLO leader Mahmoud Abbas warmly welcomed the events. Morsi was a strong supporter of the PLO’s rival, Hamas.

The reactions in the region are all over the place, and there are few patterns. Countries that are at daggers drawn over Syria were nevertheless supportive of Morsi’s overthrow.

There are two main conclusions here. Countries’ leadership looked at their own situation when they considered what happened to Morsi. Those who would want to be rescued from an ascendant Muslim Brotherhood in their own country– the GCC, Iraq and Syria — tended to support Adly Mansour and Gen. al-Sisi.

Countries whose rulers saw themselves as participating in Morsi’s brand of democratic fundamentalism–Turkey and Tunisia– angrily denounced the events as an illegitimate coup.

Turkey and Tunisia, it seems to me, although they are outliers on the overthrow of Morsi, are in the vanguard of Middle Eastern politics. The region can only flourish if governments make a place for Muslim democrats. The lesson the latter must learn, from the overthrow and from the regional reaction, is that once elected, you still have to govern democratically.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved