With the opening of Paul Greengrass’s film “Captain Phillips,” written by Billy Ray and starring Tom Hanks, the phenomenon of piracy in the waters off the Horn of Africa is back as a topic of discussion.

This CNA study by Ghassan Schbley and William Rosenau says that piracy took off after 2006 after the fall of the Islamic Courts Movement government, which was puritanical and Taliban-like and stopped piracy while it was briefly in power.

Piracy was big business. The CNA report says that in 2006-2011:

” an estimated 3,741 crew members representing 125 different nationalities were held for ransom by pirates, some for as long as three years. Nearly 100 seafarers are estimated to have died at the hands of Somali pirates. The economic costs of Somali piracy have been considerable—$18 billion in annual losses to the world economy in 2010.”

The pirates themselves have a narrative of foreigners exploiting their coastal waters and over-fishing, harming the Somali artisan fishermen, who were the first to turn to piracy out of a mixture of desperation and anger. This origin story is probably true, and the problem of poaching is significant.

CNA notes,

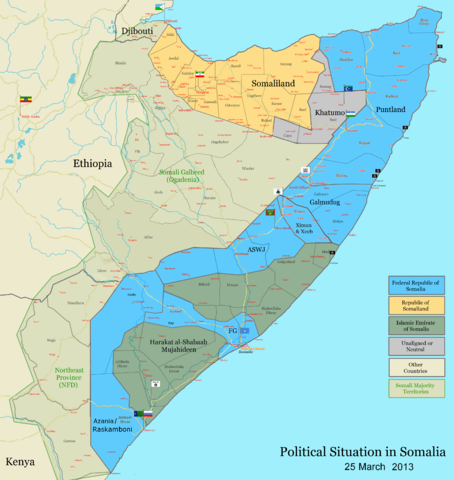

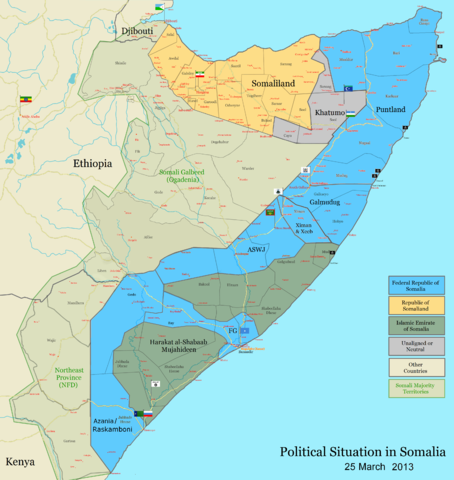

“Somali waters, particularly off the coast of the semi-autonomous state of Puntland in the country’s northeast, contain some of the world’s most important stocks of tuna, anchovies, sharks, rays, lobsters, and shrimps… one study suggests that more than more than half of the total annual catch in the wider western Indian Ocean is illegal. Within Somali waters, possibly hundreds of vessels participate in this depredation. Exact numbers of [poaching] fishermen are impossible to glean, but there is credible evidence that foreign fishing occurred within 200 nautical miles of Somali coasts in the 1990s and early 2000s. As late as 2005, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimated 700 foreign-owned vessels engaging in “unlicensed” fishing off the Somali coast. The reduced catches of small-scale Somali artisanal fishers is almost certainly a byproduct of overfishing by commercial and industrial vessels from outside the region.”

But the authors argue that it only takes us so far, because later on piracy grew into a cartel-like business and attracted a lot of people who had never fished a day in their lives. Moreover, they say, most Somalis were never directly affected by the poaching, since once you get away from the coast they aren’t big fish eaters and prefer meat. I’m not sure the effect of poaching can be so easily dismissed, however. There is an enormous opportunity cost for Somali fishermen in having foreigners carry away expensive catch like tuna. They might not have stayed ‘artisanal’ fishermen and could have brought money into coastal towns and cities.

In any case, what is important is that by 2009 the pirates were a criminal cartel.

Moreover, poaching was only one of many forms of economic dislocation that led young men to take up a risky occupation, argues Christian Bueger. The faction-fighting and poor security situation in Somalia, in which the US, Saudi Arabia and al-Qaeda were involved, drove some of the despair.

Thus, I wonder if the slightly improved security situation under an elected president is part of piracy’s recent decline. There is also, Bueger says generally less support for piracy, since it turns out to expose local communities to reprisals. But also, the shipping companies have now armed their vessels and there is better international maritime cooperation in forestalling it.

But no one thinks the phenomenon is over. It is worrisome that former pirates have often turned to smuggling, human trafficking, and involvement with al-Qaeda affiliates.

One thing is clear. Effective development aid for Somalia is about the best spent money you could imagine.

© 2026 All Rights Reserved

© 2026 All Rights Reserved