(By Juan Cole)

The tale of two constitutions, 2012 and 2014, in Egypt has to be seen in my view as significantly an urban-rural struggle. Neither referendum had a big turnout, but the one in 2012 only attracted 32.8% of the electorate, while apparently the turnout in the referendum just held was slightly higher at 36.6%.

Both processes were deeply flawed. In 2012, the Morsi government cracked down hard on protesters at the Presidential Palace, killing 6 of them in one day in early December. The judges, who were supposed to oversee the balloting and secure the ballot boxes, mostly went on strike. Brotherhood lawyers brought in to substitute could not have been trusted to be impartial. But the atmosphere in early 2014 was even more repressive, with even small demonstrations urging a “no” vote being disallowed and protesters arrested. The Muslim Brotherhood has been disbanded, expropriated and declared a terrorist organization. Some sources allege that 21,000 have been arrested since July. Obviously, this referendum cannot be certified to international standards as a free and fair election.

Still, the numbers coming out may tell us something if we look at them in context.

Clearly, many secularists, centrists, leftists and liberals were willing to come out and vote “no” in 2012. Important political forces rallied to try to defeat the Morsi constitution, to their credit, and they came within 14 points of doing so. In 2012 Cairo and Alexandria were solidly against it. In 2014, the Muslim religious forces, in contrast, simply refused to show up at the polls. In addition, some left-liberal groups also boycotted. The turnout in rural areas that tend to support the Muslim Brotherhood was low.

One difference is that only 63% of the voters in 2012 approved of the constitution. 63% of 32.8% is just over 20%. So only 1/5 of the electorate actually voted for the Morsi constitution.

In contrast, the government is saying that 97% of those who voted this week voted “yes.” In other words, the vast majority of those voters who opposed this constitution simply did not vote at all because of the boycott announced by the Muslim Brotherhood and the refusal of the Salafi fundamentalists to heed the call of their Nur Party to support the constitution (Salafis have distinctive dress, and were conspicuously absent from voting lines in places like Alexandria where they have some strength).

But 97% of 36.6% is 35.7%. So although a majority of Egyptians either abstained from voting or boycotted the vote, a bigger *proportion* of the electorate approved this constitution than the one in 2012.

This week, 19.4 million voters approved the more secular constitution.

Neither showing is very good for the organic law of a society. I suspect Gen. Abdel Fattah El Sisi, who orchestrated this new constitution and the referendum, must be disappointed that only a third of eligible voters turned out, not the half the Egyptian military had been hoping for.

What is striking in both referendums is the rural-urban split and the north-south split. The big urban areas in the center and north did not like the Muslim Brotherhood constitution, which put the interpretation of some Egyptian law (the statutes drawn from Islamic principles) in the hands of the al-Azhar Seminary, a step toward Iran-style theocracy.

Rural areas were more enthusiastic, though in the Delta in the north there is a substantial rural population that supports populism and leftist nationalism and has been tied to the state created by the young officers in 1952. The Egyptian military carried out land reform, breaking up enormous haciendas, and so created a rural middle class. Many in that class are still grateful to the government for their land. So the rural areas were contested between the Muslim Brotherhood and the nationalists, but in 2012 the Brotherhood had a majority in those governorates. The purchase of nationalism and gratitude to the military is substantially less in the southern rural provinces.

Turnout for the secular constitution this week was typically higher in urban areas than in rural ones. In Cairo, the turnout was 42% this time, compared to only 33.5% in 2012.

In contrast, in rural Minya south of Cairo, only 26% came out this time, whereas nearly 34% did in 2012. El Fayoum also saw a big fall-off in participation (Muhammad Badie, the imprisoned Supreme Guide of the Brotherhood is from there).

In some rural provinces, such as Gharbia, a majority of the electorate came out and most voted yes. Only a third voted in 2012, and a majority of those voted for the Brotherhood position. The only way to understand these numbers is to see Gharbia as deeply polarized, so that most nationalists and rural leftists boycotted in 2012, but they came out this time. In other words, there is very little overlap between the voters of 2012 and those of 2014 in this province. It is also likely that many voters changed their minds in the interim.

A Gallup poll showed that support for Morsi and the Brotherhood fell in Egypt from 50% late in 2012 to only 19% in early June of 2013. It likely has fallen further since then. Among Morsi’s failures was not stocking enough imported wheat in warehouses, causing rises in the price of bread, which hurts the poor above all.

So some northern rural governorates complicate the over-all story of an urban-rural split in Egypt. But the trend is certainly visible if you take the southern rural provinces into account in both elections.

Egypt is still only about 50% urban. Probably its urbanization has been slowed by a stagnant economy since 1970, which has led to millions living and working abroad instead of emigrating to the cities. Urban youth in particular are less religiously observant and more secular-minded than the rural population. Rural areas have lower literacy and lower internet penetration than urban ones.

Another divide between the two referendums has to do with the Coptic Christians. Many Copts boycotted the 2012 referendum, or voted “no.” The Coptic pope asked the Christians to support the 2014 constitution and from all accounts they did so. Copts are 10% of the population or about 5.3 million of the 53 million voters, so if they mostly sat out 2012 but mostly came out and voted “yes” during the past two days, they could account for 4 or 5 million of the extra 10 million votes in favor of this constitution over the 2012 document.

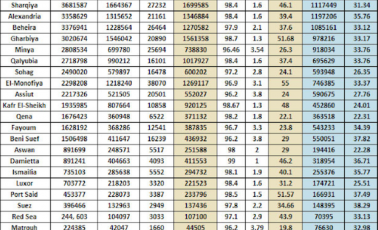

Here is the breakdown of the 2014 vote according to preliminary numbers, with some comparisons to 2012, by governorate, according to al-Ahram Newspaper:

——

Related video:

VOA reports on the referendum in Egypt :

© 2026 All Rights Reserved

© 2026 All Rights Reserved