(By Erdağ Göknar)

The novel Snow by Nobel-prize-winning Turkish author Orhan Pamuk exposes the logic of Middle Eastern nationalism. Not surprisingly, political conspiracy has a prominent role to play in it. Turkish realities and their ideologically colored representations are constantly switching places in the novel.

As a result, it becomes harder and harder for characters to distinguish fact from fiction. For example, the newspaper prints events that will happen rather than ones that have happened; a military coup erupts from the performance of a didactic play; the mere hint of a political Islamic electoral victory provokes the (then) established secular order to acts of violence; women who want to veil are prevented from doing so and are driven to suicide because of what veiling represents to the state. Similar surreal scenes have been common in modern Middle Eastern history and are currently playing out in Egypt, Syria and Libya.

In this world, rhetoric and reality are often conflated. But in Turkey today, we are witnessing the emergence of something beyond the fictions of political representation: the rise of conspiracy as a political force.

The discourse of conspiracy is so powerful that incriminating evidence of corruption against Turkey’s ruling AK (Justice and Development) Party, which first led to the resignation of four ministers, has done little to dampen Prime Minister Erdoğan’s political power before local (March 30), presidential (August) and general elections (June 2015). The conspiracy theory tells an alternative story to explain away an inconvenient truth.

The AKP, which has always presented itself as the moral, ethical and honest alternative in Turkish politics is now up to its ears in tender rigging, bribery, cronyism, nepotism, obstruction of justice, and influence peddling. The rhetoric of conspiracy – which politicians have raised to a literary talent – is one of the main tools Erdoğan has been relying on to see him and his party through the election cycle amid the widespread corruption and bribery scandal. And he has a number of willing media outlets to broadcast his message.

Erdoğan would win the international award for the best conspiracy theories in 2014, were there such a thing. The prime minister’s recent repertoire of conspiracies includes reference to various colluding anti-Turkey groups such as the “interest-rate lobby” (economic forces jealous of Turkey’s financial success); the “preacher’s lobby” (the influence of Islamic scholar Fetullah Gülen and his followers); the “porn lobby” (those opposed to a recently signed internet censorship bill); the “robot lobby” (a misnomer that refers to social media from Tweets to YouTube); and the well-worn USA-Israeli axis (which now apparently includes Gülen). But that’s not all.

The prime minister has used conspiracy to marshal lawmakers and the judiciary against various “states within states”, notably the “deep state” (the military-secular alliance), and now, the “parallel state” (Gülen’s influence in Turkey’s police, judiciary and parliament). All of these dark forces are working to undermine Turkey and the Turkish Model and there is only one man who can stop them – and by the way, he needs your vote.

Not surprisingly, conspiracy, and the political theater that it gives rise to, finds its way into Turkish literature as a political trope. In fact, one of the arguments of Pamuk’s Snow is that it is the populace that suffers when politicians use conspiracy to blur the lines between fact and fiction. A number of books discuss the role of conspiracy in the Middle East but none of them addresses the ties between conspiracy, politics and literature. In my work, I argue that fiction, including conspiracy, reveals the cultural logic of Turkish politics. That is, in Turkey, the truth of political life can be found in its fictions, which are often opposed to the abuses of state power such as we are witnessing in Turkey today.

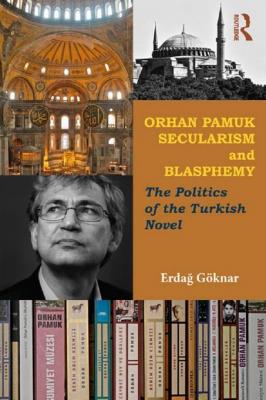

Erdağ Göknar is Assistant Professor of Turkish Studies at Duke University and author of Orhan Pamuk, Secularism and Blasphemy: The Politics of the Turkish Novel (Routledge, 2013)

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved