(By Pippa Holloway)

Nearly six million Americans are prohibited from voting in the United States today due to felony convictions. Six states stand out: Alabama, Florida, Kentucky, Mississippi, Tennessee, and Virginia. These six states disfranchise seven percent of the total adult population – compared to two and a half percent nationwide. African Americans are particularly affected in these states. In Florida, Kentucky, and Virginia more than one in five African Americans is disfranchised. The other three are not far behind. Not only do individuals lose voting rights when they are incarcerated, on probation, or paroled, a common practice in many states, but some or all ex-felons are barred from voting. All six of these states have non-automatic restoration processes that make it difficult or impossible to have one’s rights restored. Not coincidentally, all of these states maintained a system of racial slavery until the Civil War.

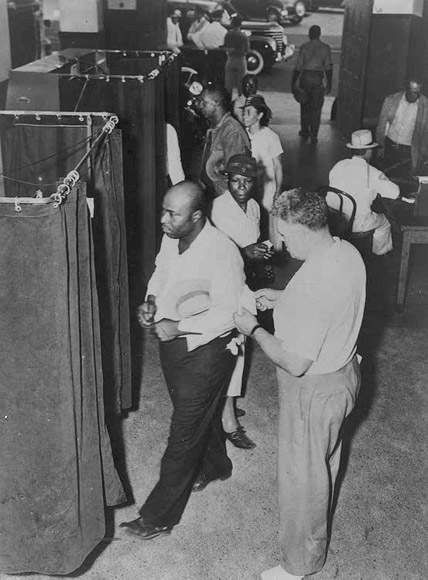

Voters at the Voting Booths. ca. 1945. NAACP Collection, The African American Odyssey: A Quest for Full Citizenship, Library of Congress. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

At the other end of the spectrum are northeastern states, mostly those in New England, which put up few obstacles to voting by convicted individuals. Maine and Vermont are the only states in the nation that do not disfranchise anyone for a crime, even individuals who are incarcerated. Among the remaining 48 states, Massachusetts and New Hampshire disfranchise the smallest percentage of convicted individuals. Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Pennsylvania are also far below the national average.

Generalizations about regional difference are complex should be made cautiously. Although the six states with the highest rates of disfranchisement are all in the South, six other states also impose life-long disfranchisement for some or all felons. Arizona and Nevada have relatively high rates of felon disfranchisement. Midwestern states, particularly Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, and Michigan, have low rates of felon disfranchisement, as does North Dakota. Nonetheless, the Northeast and South stand in stark contrast.

Regional differences in felon disfranchisement today are the result of regionally divergent histories of slavery and criminal justice. New England states had outlawed slavery by 1800. Soon, they also stopped treating convicts like slaves, barring state-administered corporal punishment for criminal offenses in the first few decades of the nineteenth century. Instead, northeastern states embraced an ideology of criminality that emphasized rehabilitation. This attitude toward both slavery and punishment led many citizens and lawmakers in the northeast to oppose disfranchisement of convicts or at least curb the reach of this punishment. In the colonial era, Connecticut limited the courts that could deny convicts the vote. Maine’s 1819 constitutional convention rejected a proposal to disfranchise for crime. Vermont ended the practice in 1832. In other northeastern states proponents of such disfranchisement measures faced strong opposition. For example, Pennsylvania’s 1873 constitutional convention restricted felon disfranchisement to those convicted of election-related crimes; an effort to disfranchise convicts in Maryland in 1864 passed only after a long debate.

In contrast in the nineteenth-century South two groups were permanently cast out of full citizenship: African Americans and convicts. Although the enslavement of African Americans ended in 1865, “infamy” – the legal status of those convicted of serious crimes – was imposed on a growing number of the new black citizens. Accusations of prior crimes were used in the 1866 election as one of the first tools used to deny the vote to former slaves. In the 1870s, nearly every state in the former Confederacy (Texas being the exception) modified its laws to disfranchise for petty theft, a move celebrated by white leaders as a step toward disfranchising African Americans.

The legacy of slavery and segregation in the South is important to this story but so is the different regional trajectory of criminal justice. All southern states except South Carolina and Georgia (states today that still have among the lowest rates of disfranchisement in the South) enacted laws disfranchising for crime between 1812 and 1838, and there is little evidence of dissent or debate over this punishment anywhere in the region. Furthermore, southern states rejected the concept of criminal rehabilitation and focused instead on punishment. After the Civil War “convict lease” systems replicated in many ways the system of slavery for those who fell into it, creating a class of mostly-black individuals who were subject to physical punishment, public abuse, and humiliation, and denied voting rights.

In the past, as is also true today, individuals with criminal convictions fought long battles to regain their voting rights. Far from being a population that is uninterested in politics, individuals barred from voting have challenged obstacles to re-enfranchisement and overcome tremendous hurdles to have their voting rights restored. Consider the case of Jefferson Ratliff, an African American farmer living in Anson County, North Carolina, who in 1887 paid the court an astounding $14 to have his citizenship rights restored, ten years after his conviction for larceny (including three years’ incarceration) for stealing a hog. In Giles County, Tennessee in 1888 a man named Henry Murray paid $2.70 in court costs in an unsuccessful effort to have his voting rights restored. In other cases, poor and illiterate individual petitioners facing a complicated legal process sought help from friends and neighbors. In Georgia, Lewis Price petitioned Governor William Y. Atkinson in 1895 for a pardon so that he could vote. He explained, “I am a poor ignorant negro and I have no money to pay to the lawyers to work for me. So I have to depend on my friends to do all of my writing.”

The historical record shows that state and local governments have consistently failed, throughout the nation’s history, to enforce these laws in a fair and uniform way. Coordinating voter registration lists with criminal court records and pardon records — difficult in today’s world of information technology — was nearly impossible in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. People who should have been able to vote were often denied the vote due to false allegations of disfranchising offenses; convictions were secured through suspect judicial processes prior to an election for partisan ends; and people who should have been disfranchised often voted. Sometimes these appear to have been honest mistakes made by officials charged with merging complicated statutory and constitutional requirements with voter registration data and court records. In many cases though, other agendas—partisan, racial, personal—seem to have been at work. In short, felon disfranchisement laws have long been subject to error and abuse.

Race both rationalized and motivated laws imposing lifelong disfranchisement for certain criminal acts in the post-Civil War period. Since then a variety of factors have led to the persistent sense, particularly in southern states, that individuals with prior criminal convictions are marked with a disgrace and contamination that is incompatible with full citizenship. Felon disfranchisement today preserves slavery’s racial legacy by producing a class of individuals who are excluded from suffrage, disproportionately impoverished, members of racial and ethnic minorities, and often subject to labor for below-market wages. In these six southern states, the ballot box is just as out of reach for former convicts as it was for enslaved African Americans two centuries ago.

Dr. Pippa Holloway is the author of Living in Infamy: Felon Disfranchisement and the History of American Citizenship, published Oxford University Press in December 2012. She is Professor of History at Middle Tennessee State University. Contemporary data comes from Christopher Uggen, Sara Shannon, Jeff Manza, “State-Level Estimates of Felon Disenfranchisement in the United States, 2010.”

Mirrored from The Oxford University Press Blog

—–

Related video added by Juan Cole:

ACLU of Wisconsin from last year: “Felon Refranchisement and Disparity ”

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved