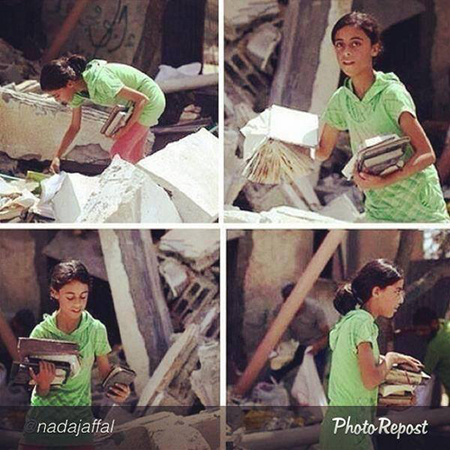

Girl in Gaza. (origin of photos unknown)

by ROBIN KIRK for ISLAMiCommentary

Of all of the images of the destruction being visited upon Gaza and Israel, why did the picture of a girl retrieving her books from the rubble stop me cold?

The image was originally posted, as far as I can tell, by the Palestinian Information Center soon after Israel’s bombing began. As the world knows, Hamas has also been sending rockets into Israel, allegedly using civilian buildings as cover.

So much for the obligatory provisos. That’s not really what I want to write about.

A friend posted the girl’s image on Facebook. It might be propaganda. I don’t care. There is nothing staged or fake about her expression as she locates her belongings.

As she rescues her books.

To find the photo’s origin, I went through hundreds of ghastly images. Fathers screaming at the cameras. Mothers collapsed. On the Internet, people shout and shout and shout some more. The grief is unbearable – I mean I cannot bear it – and so I continue my search for that simple photograph of that bookish girl.

The image seems quiet for such a raging fight. Hushed. A teen, caught unawares, shakes the dust off what could be school textbooks or even a picture book or two. If my mother’s eyes don’t deceive, she also manages to rescue her pencil case.

In her influential book on war imagery, Susan Sontag demolishes the assumption that gory images prompt action. The “quintessential modern experience” of viewing savagery, she wrote in Regarding the Pain of Others, does many things, but rarely does it lead to coherent and effective action to halt atrocities.

Images objectify. They inadvertently beautify. Too often, they are so horrible and heart-wrenching – the images of the broken bodies of the little boys on the beach, a parent cradling a limp infant – that we metaphorically turn the page or (to use more contemporary parlance) click away.

But Sontag doesn’t allow us to elude that pain with easy cynicism. “Let the atrocious images haunt us,” she writes. “Even if they are only tokens, and cannot possibly encompass most of the reality to which they refer; they still perform a vital function. The images say: This is what human beings are capable of doing – may volunteer to do, enthusiastically, self-righteously. Don’t forget.”

What struck me about this particular image of the girl was not gore. There is none. Gore alone does not arouse compassion or even understanding. To the contrary, graphic violence usually pushes people away. People don’t take an interest in human rights abuses because of gore, but rather through an emotional connection with the human beings who suffer.

As I stared at the photo, I heard a familiar voice from one of my favorite books.

“First the colors,” the voice says (the girl’s green top, the white of the rubble). “Then the humans.” (Her beautiful eyes, doing something so unremarkable that it is completely remarkable).

“That’s usually how I see things,” Death explains on the first page of Marcus Zusak’s The Book Thief. “Or at least, how I try.”

The Gazan girl is unmistakably Liesel, Zusak’s heroine, orphaned in World War II Germany. An illiterate, she steals her first book, The Gravedigger’s Handbook, from the boy who dropped it after burying her little brother. Under the tutelage of her beloved adoptive parents, Liesel learns to read as Germany crumbles under sustained Allied bombing. For a time, their little family shelters a Jewish man and he survives the Holocaust.

Liesel saves a life she didn’t mean to. She acted honorably, though that was never planned. Others made the war and fought it. All she wanted to do was grow up.

What connection could a work of literature set in 1940s Germany possibly have with an unrelated photo about a contemporary tragedy set in the Middle East?

Everything, as it turns out.

At its core, The Book Thief is not about World War II. The setting could be Syria. It could be the Congo. It could be Chicago’s South Side, where children are killed because they step into the paths of bullets that are only sometimes meant for them. The picture of the Gazan girl tells a story that lifts beyond accusations of Hamas’ deliberate sacrifice of civilians and denunciations of Israel’s terrifying brutality.

Because of The Book Thief, this girl in Gaza is as real to me as any of my child neighbors. Fiction may seem like an escape from such terrible times, but it’s what brought me to the edge of that rubble, so close I can feel the grit on my fingertips.

I want to know the girl’s name. I want to know she’s OK. I want to know what was so important about those books, those specific books, and why she searched the rubble for them.

I want to sit next to her and watch her turn the pages, and tell me that what’s on them is funny or interesting or completely boring or silly.

I want to know that she’s OK, but I already said that. I am the kind of reader that skips to the end, to know that my time is worth it. I want to know she’ll survive, like Liesel. I want her to survive, like Liesel.

And if he needs to, I want Zusak to lift her from that rubble and tuck her safely between the pages of his book, so that she’ll be safe.

Above all, I want her to be safe. I want all of the Liesels, the thousands of them in Gaza and Israel, to be safe.

I would say we are in a dialogue of the deaf, but that’s not true. The deaf speak with elegant movements, a dance of words. Tragically, this place is familiar. Writing after the end of World War II, the author of Charlotte’s Web despaired over the fate of the world. According to one biographer, he worried that his tales were trivial and even futile.

But what is a tale after all but a shard of humanity in the rubble? The author and the reader conspire to make a story about what it is to be human, any human, not just yourself but always, of course, everyone. Whether this photographer meant to or not, he or she did the same.

I can’t recommend that you retreat to fiction to escape this nightmare. It just may be that Liesel waits for you in the words, her hand on a book.

“Countries are ransacked, valleys drenched with blood,” White wrote. “Though it seems untimely I still publish my belief in the egg, the warm coal, and the necessity for pursuing whatever fire delights and sustains you.”

Every one of the dead is Liesel.

Robin Kirk

Robin Kirk teaches human rights at Duke University. A writer, she has published widely on human rights. She is currently completing a novel that includes human rights themes.

Mirrored from ISLAMICommentary

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved