By Shaun Randol

There is not one positive news story on the front page. The two news organizations might as well tack up a single headline—“Africa Implodes”—and call it a day. The negativity, by the way, is not limited to the Western media. A snapshot of headlines on the same day presented by AllAfrica.com reveals an identical sentiment:

In all, 34 headlines from three resources and not one of them is immediately apparent as being good news. (Gay Rights in DR Congo”?? Could go either way…) With all of this depressing and pessimistic news, it’s no wonder Americans have a skewed outlook of what’s happening on the African continent, where in more than 50 countries close to 2,000 languages are spoken.

Opinion polls on what Americans think of Africans in general, the continent as a whole, or even individual countries are so scarce I couldn’t find a single one. (There are studies on opinions of sub-groups, such as African-American or Arab-American opinions toward Africa or particular countries therein (and vice versa), and a few on opinions of U.S. foreign policy in places like Egypt, but even these are hard to come by.). Therefore, a few reports on U.S. citizens’ misconceptions of the continent can be used as an approximation of attitudes toward and knowledge of the diverse continent. For one, major news outlets like CNN have failed time and again to properly locate African countries on a map, mistaking, for example, Niger for Nigeria. Even NBC News anchor Brian Williams once mistook Kenya for Nigeria in speaking about Boko Haram kidnappings. And in an online quiz asking readers to locate African countries on a map, The Washington Post found that, “according to data from more than 40,000 respondents, the median country was identified correctly less than half of the time, with South Africa being the most recognized country, and Gambia the least.” (Never mind that a former vice presidential candidate thought the entire continent was a single country.)

Misunderstandings and ignorance of Africa are not limited to average citizens, politicians, and the news media. Earlier this year, the Africa Is a Country blog triggered a widespread discussion in literary circles about stereotypes when they published a collage of dozens of book covers of so-called African literature that feature the acacia tree. “In short, the covers of most novels ‘about Africa,’” wrote Africa Is a Country, “seem to have been designed by someone whose principal idea of the continent comes from The Lion King.”

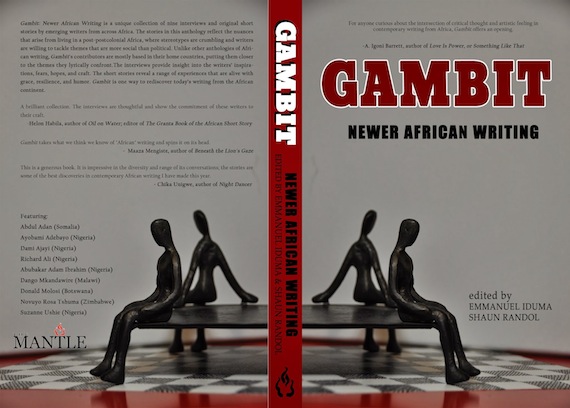

Which is why, when we published Gambit: Newer African Writing, we reached out to an artist from Burma to design the cover. As a result, the cover art depicts nothing stereotypical of “Africa” or what people would assume to be “African”—acacia trees, savannahs, impoverished children, or menacing warlords. The cover, featuring pensive silhouettes sitting above a checkerboard floor, directly reflects the mindsets of the authors within.

Despite what you might read online today or see on the evening broadcast, there is good news coming from Africa. Sometimes to find that news, however, you must look beyond the headlines. Literature can be that venue.

It was Czesław Miłosz and Milan Kundera to whom Americans turned when they sought news beyond the political spectacle put on by the elites in the U.S, Western Europe, and the U.S.S.R. during the Cold War. Today the same information-hungry audiences turn to the literary works of Liao Yiwu and Ilham Toti for insights into what life is really like in China.

That kind of intimate observation of day-to-day living… loving… working… playing… and yes, dying is exactly what you’ll find in our book, Gambit. But my co-editor—Emmanuel Iduma (from Nigeria)—and I take it a step further: each short story in the anthology is paired with an interview with the author. Readers are exposed to the inspirations, fears, dreams, and unique life philosophies of these individuals, ten in total from Botswana, Malawi, Nigeria, Somalia, and Zimbabwe. These three women and seven men represent a rich and diverse cross-section of continental experiences.

The countries featured in Gambit are as different from one another as Canada and Mexico, two very different states that happen to be on the same continent. And yet with an adjustment of a minor detail here or there, the stories could just as well take place in Toronto or Juarez. That’s because the themes are not “African;” they are human. Take, for example, Dami Ajayi’s (Nigeria) story about how smartphone technology interrupts a romantic relationship. Or Dango Mkandawire’s (Malawi) vignette on schoolyard bullying. Or the story by Donald Molosi (Botswana) featuring unrequited love between two men. Those stories do not take place under acacia trees—they take place in a 21st century globalized world.

When we begin to see the countless, vexing, and poetic layers that make up Malawi or Somalia or the whole darn continent, we begin to humanize “them,” the “other” to which bad news seems to be happening to all the time, somewhere else. For if we are to live together in peace, we must first understand who and what makes up our earthly neighborhood and to understand that “Africans are just like us!” Maybe then news editors will begin to promote an alternative narrative, one not of doom and gloom but rather of art and optimism.

Gambit is a humble gesture toward the betterment of our world made through informing and storytelling. Let us make an effort together to better understand each other, so that we’ll be more inclined toward cultural—not violent—engagement. Wouldn’t that be some good news?

Shaun Randol is editor-in-chief of The Mantle, a member of PEN American Center and the National Book Critics Circle and co-editor of the co-editor of Gambit: Newer African Writing

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved