By Philip J Cunningham

Everyday hundreds, if not thousands of Chinese and Japanese kill one another on Chinese television. Hundreds of Anti-Japan war dramas were churned out last year and the genre dominates China’s airwaves round the clock like never before, even though eight decades have gone by since Japan’s war of invasion.

What’s more, the 2014 fall television season is packed with more patriotic drama than usual, reflecting unresolved tensions with Japan and a series of war anniversaries ranging from the September 18 date marking the invasion of Manchuria to the December 13 commemoration of the Nanjing massacre.

Scene from a recent Chinese TV drama showing pain and perfidy of Japan’s invasion

In recent years Chinese authorities have used television, indignant news reports and patriotic drama alike to bash Japan, but the waves of anti-Japanism rise and fall even though anniversaries are static, which begs the question, why now? Why in such volume, and why so much of it all at once?

Seen from the ground in China, from the pained point of view of a victim nation, the story of how Japan raped and pillaged can’t be told often enough, or in indignant enough a fashion. China’s contemporary cultural czars exploit this to crank out a wide range of propaganda product that helps keep the historic indignities alive, but it’s not history for history’s sake, as the same czars are adept at burying history when it serves political purpose.

The anti-Japan campaigns are not conjured out of thin air either, but often are launched in response to words and actions by Japan that insult China’s sense of itself. Often provoked by specific incidents, Beijing’s changing anti-Japan line is part and parcel of a broader policy to shore up contemporary Chinese identity while simultaneously pressuring Japan to own up to its own history. But there are grassroots pressures as well. Japan invaded China through treachery and force and wreaked great havoc on the lives of tens of millions, so it’s not something easily forgiven or forgotten. Each time a national politician in Japan denies, dismisses or whitewashes the miserable and horrific decade of warfare in which China was battered and millions of civilian lives were lost, the authorities rush to speak out in indignation lest they fall behind the curve of popular opinion.

Chinese actors ham it up playing the Japanese villain

Although anti-Japan media campaigns are an exercise in power in their own right, the mechanical summoning up of past misdeeds to arouse passions in the present, the historic roots of the anguish are secure. Sometimes the anti-Japanism is just an excuse, shamelessly exploited for other purposes. The rise of such media campaigns, almost non-existent in the days of Mao and Deng, is no doubt in part a reaction to the rise of revisionism in Japan. But it is also a useful way to whip up solidarity and unity in the vacuum created by the collapse of communism as a guiding ideology. The Japan issue is so emotional for most Chinese that it can be harnessed and then whipped to distract a restive populace from domestic problems. The story of communist China is inseparable from the anti-Japan struggle ñMao once jokingly thanked Japan for creating the conditions for successful revolution- and to this day it can be used to stoke nationalism, especially among the young.

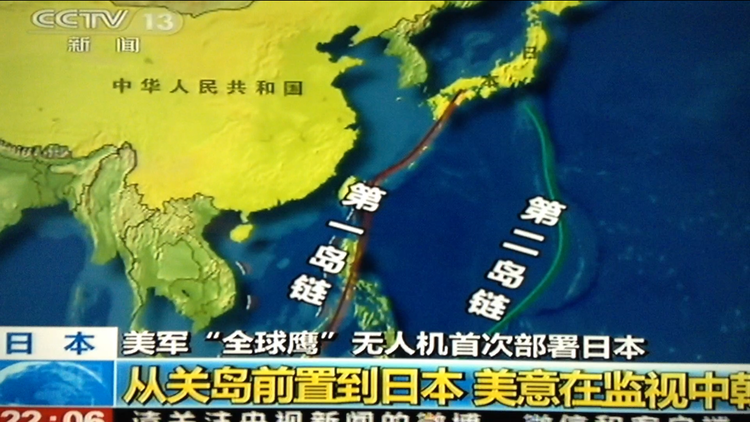

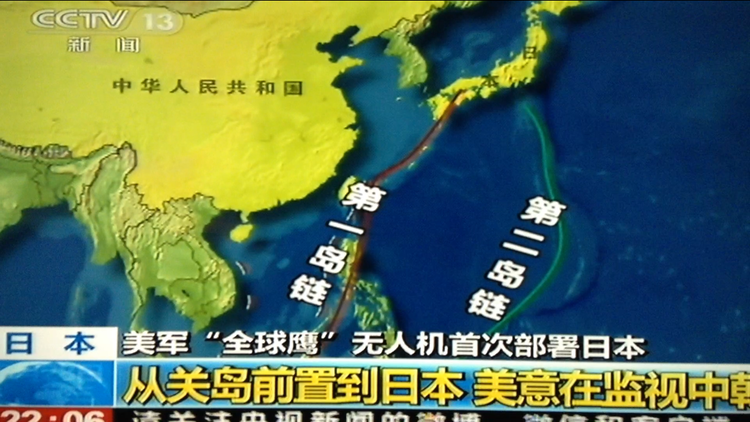

The timing by which China decides to launch it’s patently undiplomatic anti-Japan campaigns bears a relationship to perceived provocations, and is in this sense born of reaction, but it is not so much a matter of reacting to provocations as it is a matter of what provocations China’s leadership elects to react to. Textbooks? That problem has been around for a while, a backburner issue. Comfort women? It’s an irritant, but South Korea has stepped forward to guard the front line on that one. Territorial disputes? The most dangerous of all, and tightly-controlled from the center, although there is some evidence of local commanders making aggressive moves on their own initiative and the ever-present danger that an accidental collision might start a small war. Military discipline and control are paramount when it comes to guarding territory and trump the seasonal needs for anti-Japan campaigns. For the media machine to mess unduly with the territorial issue is to play with fire, not just in terms of triggering armed conflict, but populist passions. For the control-minded apparatchik, Diaoyu/Senkaku and other island disputes are too hot to play around with for ulterior purposes.

Which leaves Yasukuni, the most innocuous and unnecessary source of conflict, but in some ways the most heated source of contention. In practice, it’s just a walk in the park. Innocuous is not to say innocent, symbolic actions can inflict great hurt, and those engaged in the Yasukuni shuffle are well-aware of the hurt it causes. Their ritual steps salute the memory of Japan’s war-makers, including convicted war criminals, while ignoring their many victims. It’s a picturesque stroll in a shady, leafy setting, but it tramples on the feelings of millions.

The gate to Yasukuni Shrine on an ordinary day last May

Shrine visits tend to follow a seasonal calendar, a useful consideration when launching a coordinated campaign. Preparations can be made in advance and rolled out on cue, but can be called off on short notice too. In the same way that sports events get excellent coverage because they take place in a set arena within known parameters, the dramatics of Yasukuni are perfect for newspaper and television coverage.

China Daily, the leading English language state newspaper in China, has run some 3000 articles about Yasukuni since it digitized its archives in 2001. Looking at China Daily archives for December 2013, the month Japan’s Prime Minister Abe last visited Yasukuni Shrine reveals some interesting patterns. The headlines preceding the unannounced visit are breathlessly expectant. Will he visit or not? Has diplomacy at last won the day? If he does visit, does he realize the consequences?

Then on December 26, 2013, during a quiet news period in the lull of the impending New Year’s holiday, Abe strode into Yasukuni Shrine and performed a brisk ritual in honor the spirit of Japan’s war heroes. The response from China was immediate and indignant.

The state-controlled China Daily headlines excerpted below reveal a rage that erupts on day one and grows by the day. It is barely containable by week’s end, with devilish images being invoked, even though things usually get quiet journalistically over the New Year’s holiday.

“Abe’s shrine visit grave provocation”

“China scathing on Abe’s Yasukuni visit”

“Abe’s Yasukuni Shrine visit is a dangerous step”

ìAbe’s shrine visit affronts worldî

“Abe shows his cloven hoof”

All told, China Daily racked up 46 articles (news, editorials and op-eds) on the topic for the month of December and by the end of January over 150 pieces dealing with Yasukuni had been published.

In the weeks to come, in January 2014, China’s state-controlled press continued to seethe with anger, running stories tagged with expressions such as “fury mounts” “media frowns” and “a flagrant denial of justice.” Japan is said to be suffering “world condemnation” so it “must correct mistakes” lest “outrage still fester.”

The tone begins to quiet a month or two after the event and then Yasukuni recedes to a back-burner issue, By March it is merely invoked as background to other problems and other tensions. While there’s not a month when Yasukuni is not in the news, the peaks and troughs of anti-Yasukuni invective are directly related to the visit of the Prime Minister and members of his cabinet.

In short, if Japan’s prime minister does the Yasukuni shuffle, expect a media blowout from China. A short, sharp campaign of vilification follows, restricted mainly to state media. An amping up the vitriol and the use of bombastic language is evident in the nightly news. PM Abe’s December pilgrimage to the most controversial shrine in Japan was followed by the broadcast of ìBlue Wolfî and other anti-Japan drama series in January,

For the Communist Party, the periodic venting of anti-Japanism triggered by Yasukuni visits is an easy-to-manage, playable option. The visits may annoy ordinary citizens, but don’t make the blood boil like a military clash would. The Communist Party is keenly aware that keeping things under control is necessary to its survival, so fires are not stoked unless the leadership is confident of being able to contain them.

Yasukuni Shrine attracts both the curious and the devout

Ironically enough, the much-ridiculed, detested and deplorable acting out of unrepentant state Shinto at Yasukuni Shrine is not only useful, but even somewhat desirable for China’s media mavens. It provides a safe arena in which to joust with Japan. It’s the ground for a war by other means, as manageable as a giant sports match.

The periodicity of Yasukuni is important in this respect, if there’s a blowout, it soon blows over, there’s always the next match. Looking at headlines, the focal point shifts from ìWill he go?î to ìWill he dare go again?î

Yasukuni Shrine-embracing leaders such as former Prime Minister Koizumi and the incumbent Abe Shinzo have for their part played a Yasukuni game of their own, exploiting the limited focus of the Shrine in a way that puts them in control, choosing when to go and when not to, fine-tuning the details of the ceremony, and exploiting the periodicity of it. One merely has not to go to give the impression that an important diplomatic concession has been made. A sudden visit is play to their base, knowing full well China will take offense. A non-visit is to play the diplomatic card, eschewing predictable tension in order repair tattered relations.

Abe’s December 2013 visit shows signs of such orchestration; it was played down and unannounced, tucked away in a quiet corner of the calendar, leaving a stain on the year 2013, perhaps, but allowing 2014 to get off to a fresh start. Both countries value the New Year as an auspicious time, a time for fresh beginnings, and even though the visit fell short of the New Year by just a handful of days, it put itself in the past, essentially becoming last year’s news only a week later.

The pattern of breathless speculation and trepidation in the face of possible spring and summer visits to Yasukuni by Abe can be traced in the China Daily headlines of the period, and ultimately he did not visit. But with so many journalists ready and waiting, even his non-visit was news of a sort. Had Abe turned over a new leaf? Was he offering an olive branch? Perhaps not.

In the absence of a real visit, there’s a virtual alternative, and Abe took advantage of that. As if to apologize for non-attendance, there’s a Shinto style protocol of sending a ritual gift, such as a masakaki tree, along with writing ritual words of support. When Abe attends it’s news, when he doesn’t attend it’s news too,but news of uncertain nuance. This past April Abe’s formulaic ìregretsî at not being able to show got picked up upon by a waiting and expectant press. So Abe hadn’t really had a change of heart after all. It was as Abe found a way to have his cake and eat it too, typical old Abe being sneaky again. The Chinese press understands ceremonial ritual well and had no illusions about Abe’s signal of solidarity with Japan’s neo-nationalist right, but this revelation aired to no great social effect. Over the summer, another tension-filled juncture centering on will-he-go-or-not came and went. The flashpoints didn’t flash, but it wasn’t quite business as usual, either. Still sore about the previous year’s visit, island tensions and renewed exchanges in the war of words by intemperate politicians, China made a declaration of cultural vigilance.

On August 15, 2014, the day marking Japan’s surrender in WWII, China decided to jack up the volume, announcing a new, obligatory season of ìpatrioticî and ìanti-fascistî drama on television.

China’s cultural czars, perhaps tired of passively waiting to react to each and every periodic pinprick of a provocation, decided to go on the offensive, drawing from a deep war chest of anti-Japan cultural product to launch the ìpatrioticî season of anti-Japan drama. The Fall 2014 offensive does not appear to be in reaction to any particular act on Japan’s part, but rather more as generalized response to what it might be regarded in Beijing as months, if not decades, of accumulated indignity.

As a point of comparison, the language on the Diaoyu/Senkaku conflict, which is far more fraught with danger and has immediate real-world military ramifications, is generally more measured than the very public argument over Yasukuni. Diaoyu/Senkaku-related headlines, while not without a note of indignation, do not scream and shout as much.

China calls on Asia-Pacific countries to contribute to peace and prosperity

China seeks to resolve disputes though peaceful talks

Obama criticized for Diaoyu Islands remarks

China notes Japanese military activity near Diaoyu Islands.

Might does not make right

News reports and anti-Japan dramas draw attention to Japan’s flag, unchanged from war years.

Political posturing at Yasukuni is appealing because it is essentially a cultural production, a concoction of new militancy and ancient symbols, a kind of political kabuki, that typically erupts four times a year in reflection of its seasonal character, and disrupts whatever else might be going on to the detriment of diplomacy, trade and military matters.

Thus China jacks up and tamps down the volume on its anti-Japan rants in ways designed to show vigilance and shore up patriotism, if not the high moral ground. Neither side can let go until both sides let go, and that eventually still seems a long way off. In the meantime, the proliferation of period TV dramas, in which Japan abuses China but then loses both the battle and the war, helps keep the Yasukuni demons at bay. It’s as if every Japanese denial has to be answered with dramatizations showing precisely the sort of ungentlemanly behavior that Japan claims never happened or doesn’t want to acknowledge. If ìnever forget!î is the universal refrain of oppressed peoples and victims of injustice, then China’s TV dramas, sometimes edifying and entertaining, sometimes neither, manage to serve, nonetheless, as memory aids for those too busy or too young to remember.

With regards to past disputes, it’s not so much about history, as the handling of history. With regards to current conflict, keeping things manageable is at least as important as addressing points of conflict.

Philip J. Cunningham

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved