By Nehal Amer

Over the past year Egypt has undergone harsh reforms in a narrowing sociopolitical environment. New legislation is rapidly being produced in the absence of an elected parliament—from the repressive protest law to the draft NGO law, and now to the draft labor law. This past August, the Ministry of Manpower and Migration finalized a draft of their proposed labor law. Labor reforms and the absence of trade union freedoms have been a point of contention under the various short-lived regimes in Egypt since the 2011 uprising. The ministry’s most recent draft law is viewed by labor activists as an attempt to further marginalize the rights of workers in favor of Egypt’s elites. This particular piece of anti-labor legislation is part of a coordinated effort to target recent gains for labor such as the new Investment Law , which prevents third parties from challenging contracts between the government and investors or entities—a move widely seen as an attempt to re-privatize businesses that were previously returned to the public sector.

The ministry’s proposed legislation was met with resistance by activists and trade unionists who gathered to form a grassroots campaign to mobilize for legislation that complies with fair labor standards. “The Campaign for a Just Labor Law”, according to unionist and campaign coordinator Fatma Ramadan, was organized in response to proposed reforms to the labor law in February 2014: “We decided we would establish a campaign for a fair labor law after alarming reforms were proposed under former Minister Kamal Abu Eita.” In March, the campaign released its founding statement in which it explained that “a number of representatives of labor unions, trade unions and labor leaders, as well as human rights organizations and political parties have come together to establish the ‘Campaign for a Just Labor Law.’”

Hoda Kamel, a coordinator of the campaign, explained that founding members decided to draft an alternative labor law to present to workers across Egypt’s governorates and to rework the draft according to suggestions made during workshops. Kamel explained, “We have had a number of workshops so far in Cairo, Sharqia, Mahalla, Alexandria, Suez, Zagazig, and Luxor in order to talk about the main differences between our law and the ministry’s law with workers.” A few of the main differences emphasized between the ministry’s draft and the campaign’s draft include the insurance of equity in minimum wage between private and public sector workers, unemployment benefits, and greater accountability for business owners. One of the campaign’s key differences with both current and proposed legislation is the creation of an entity comprised of representatives of the ministry, business owners, and workers. This council is tasked with formulating regulations and developing plans for employment in order to break the ministry’s monopoly on creating, implementing, and monitoring procedures.

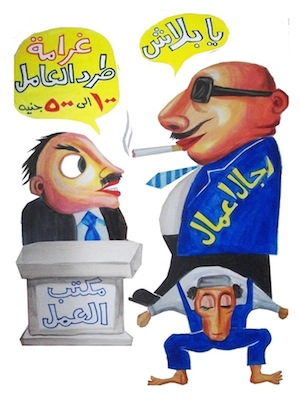

According to Ramadan, engaging with workers about the law has also resulted in raising awareness about workers’ rights in existing legislation. By encountering workers’ grievances on the ground and engaging with them through the law, many workers have been learning about the rights they already have—of which many were previously unaware. For example, in a press release published by the campaign on their Facebook page, references are made to workers who are routinely forced to sign resignation documents by employers upon hire. Additionally, campaign members are coming across cases of workers who have not been afforded breaks during the workday. Both of these practices are criminalized in current legislation. Kamel explained, “When we sat down with workers at Tawakol we discovered a worker had been working for the company for thirty-five years and was unaware of the fact that he legally had the right to a break during the work day.” Workers at the Tawakol Company for Metal Industries are on strike in response to a company decision to cut wages by 25 per cent. Kamel continued, “Efforts to raise awareness about workers’ rights have also been made by the campaign through visual art which has been incredibly important.” Campaign member and artist Nabil el-Sonbaaty has produced a number of posters delivering messages about trade union freedoms, the right to strike, and the impact of mass privatization and crony capitalism on Egypt’s poor. In a political cartoon by el-el-Sonbaaty, a man in a black suit sitting behind a desk at the Labor Office says to a businessman, “The fine for firing a worker is between 100 and 500 LE.” The plump businessman carried on the back of an emaciated worker—presumably the worker he seeks to fire—responds, “Might as well be for free!” The artist exposes the hypocrisy of a law which claims to regulate labor relations while in fact it privileges wealthy businessmen at the expense of a struggling working class. The meager expense of firing a worker is portrayed by el-Sonbaaty as nothing to a businessman who views his employees as disposable. Kamel explained, “This has been an incredibly important part of the campaign’s efforts to raise awareness because it gives people something to look at as opposed to the tedious task of reading technical texts and articles in the law.”

Campaign coordinators have focused their efforts on ensuring business owners are held accountable for arbitrary dismissals of workers, a tactic sometimes used by employers to target unionists in their factories while facing little to no consequence. According to Ramadan, the ministry’s draft law still allows for the arbitrary termination of service of workers as the fine for employers who arbitrarily dismiss workers ranges between LE100 and LE500 ($14.00 and $70.00 USD). The campaign’s draft law proposes that disputes between employers and workers be subject to the judiciary through a labor court and proposes potential jail time for employers who fail to comply with a judicial verdict or arbitrarily terminate the service of a unionist.

The ministry is expected to present the proposed legislation to parliament after elections are held in May 2015. Once workshops produce a final draft of the campaign’s proposed law, the campaign will seek to pressure lawmakers and the government into adopting just legislation that complies with international labor standards, whether it be through amending their own draft or adopting the campaign’s.

Upcoming labor legislation will substitute the current Labor Law of 12/2003, and in the absence of a Trade Union Freedoms bill, it will not only determine business relations between employers and workers but it will also determine the space afforded for workers to organize. The ministry’s draft labor law prohibits the collection of money or donations, the distribution of leaflets, collecting signatures, and organizing meetings without the consent of the employer. Additionally, Article 194 of the document bans sit-ins within the workplace that lead to a full or partial halt in work. Thus, in light of the government’s resistance to issuing a Trade Union Freedoms bill, the restriction of such activities creates an even more hostile environment for organized labor.Moreover, the ministry’s draft law does nothing to address concerns about the vast inequality between private and public sector workers in terms of wage and vacation as it continues to discriminate against the private sector by failing to establish minimum wage policies.

The campaign faces an uphill battle in Egypt’s current political environment. As Ramadan noted, “We are living in tough times, and anyone who speaks out is met with harsh consequences, but we must continue to speak out and demand the rights of workers…not only that, but we must present an alternative to what is being presented, and that’s what this campaign aims to do.”

Nehal Amer is an M.A student specializing in Modern Middle Eastern and North African Studies at the University of Michigan-Ann Arbor.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved