By Richard Foltz | —

Having committed ourselves to military involvement in Iraq, we in North America should be asking ourselves exactly what goals we hope to achieve. Personally, after recently spending three weeks in the region, I am not convinced that “preserving the territorial integrity” of the present Iraqi state should be one of them.

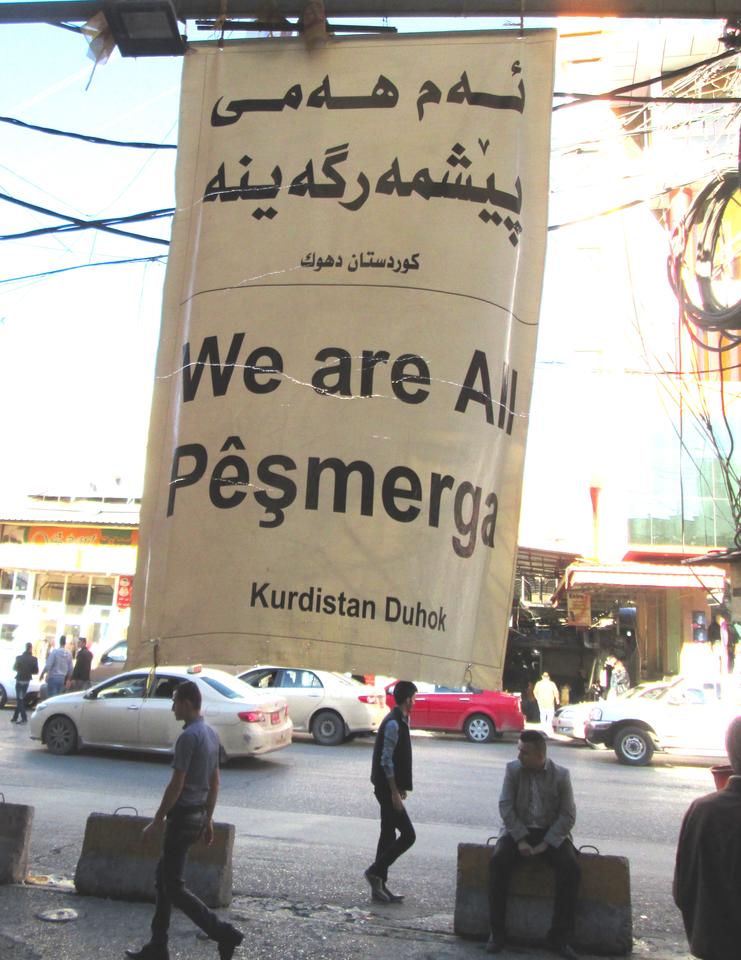

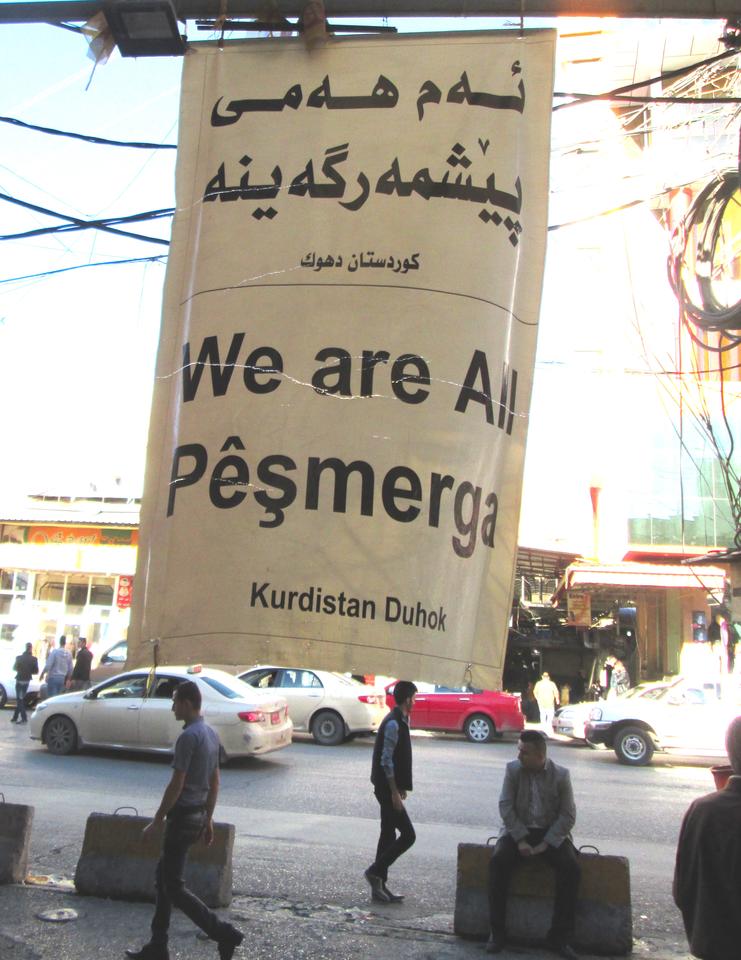

Since achieving semi-autonomous status in 1992, Iraq’s Kurds have succeeded in building a prosperous, largely peaceful quasi-independent state in the northeastern part of the country that is arguably the most stable, democratic, and tolerant entity in the entire Middle East. The Iraqi Kurds overwhelmingly desire full independence, and there is no compelling reason why they should not have it.

The three Iraqi provinces formally under control of the Kurdish Regional Government (KRG) have little in common with the rest of Iraq. The population is almost entirely Kurdish – the Kurds speak a language is closely related to Persian – and they have little affinity or affection for Iraq’s Arabs. Most of the younger generation speak little or no Arabic, preferring to learn English as their second language. Although most Kurds are Sunni, they do not identify with the Sunni Islam of their Arab neighbours which they associate with extremism. The official policy of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) is one of religious tolerance toward minority communities such as Christians, Jews, and Alevis. They accord even more respect to the much-persecuted Yezidi sect, considering that little-understood faith to be the original pre-Islamic religion of the Kurdish people. Most of the population of Iraq’s Kurdish provinces seems to share and support the regional government’s policy of protecting religious minorities and its aversion to religious extremism.

Kurdish society is conservative but moderate. Women are noticeably less present in the public sphere than in neighbouring Iran, for example, and while headscarves are not legally mandated, a large proportion of Kurdish women choose to wear them. Much-publicized images of female Kurdish fighters in Kobane and other battle zones are not mere propaganda aimed at the West, but neither are they an indication that Kurdish women are more “liberated” than others in the Middle East. Women have been active in Kurdish struggles for independence throughout the past century, and are fighting for the dream of a country, not on behalf of feminism per se.

Having enjoyed Western support for over two decades, Iraq’s Kurds are at once the Middle East’s most pro-Western people and its most faithful and reliable allies. The same cannot be said for our other supposed “friends” in the region, who have agendas that are often at odds with Western interests. Iraqi Kurds understand that they live in a rough neighbourhood, and that as a small state they cannot survive without powerful friends. They generally support the planned US initiative to build a military base near the northern city of Duhok, which is meant to reduce Western dependence on an increasingly unpredictable Turkey. Kurds are overwhelmingly friendly and welcoming to Westerners, whom they are clearly delighted to have witness their impressive achievements.

Experiencing Iraqi Kurdistan first hand, it is hard not to have a favourable impression. The region is noticeably more modern and prosperous than anywhere else in the Middle East except perhaps the Gulf states, which it resembles only in the proliferation of multi-storied shopping malls. Apart from the many refugees that have flooded Kurdistan from ISIS-controlled areas in recent months, there are no visible signs of the kind of poverty and dramatic socio-economic inequalities so prevalent throughout the Middle East. There are no slums to speak of, and most buildings are of recent construction; the pastel hues of freshly-painted homes give an air of cheeriness that contrasts markedly with the soulless grey concrete dominating other Middle Eastern cities. Iraqi Kurdistan’s prosperity is largely due to oil wealth, but this appears to be getting more broadly distributed than in the autocratic and highly hierarchical Gulf states.

The contrast between a secure Kurdish region and the miserable condition of the rest of Iraq is not accidental. (The car bombing in the Kurdistan capital of Erbil in mid-November was a warning sign, but no more an indication of general instability than was the attack on Canada’s parliament a few weeks ago.) Little unites Iraq today, other than a fossilized system imposed by the British during the 1920s after the fall of the Ottoman Empire when so many artificial states were created. The Kurds can hardly be blamed for wanting to shed the burden of a far less functional society than their own, with which they do not identify on any level. Their aspirations to full nationhood deserve our understanding and support.

Richard Foltz is Professor of Religion and Director of the Centre for Iranian Studies at Concordia University, Montréal. His recent book, Religions of Iran: From Prehistory to the Present (Oneworld Publications, 2013)

includes a chapter on the Kurdish Yezidi and Yaresan sects.

(N.B.: Guest columns do not necessarily reflect the editorial stance of Informed Comment ).

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved