By Russell Frank | (The Conversation)

Longtime New Yorker magazine staff writer Lillian Ross once admonished aspiring reporters not to write about themselves.

“As a reporter, serve your subject,” she wrote, “do not serve yourself. Do not, in effect, say, ‘Look at me. See what a great reporter I am!’”

Sounds quaint in the age of the selfie, doesn’t it?

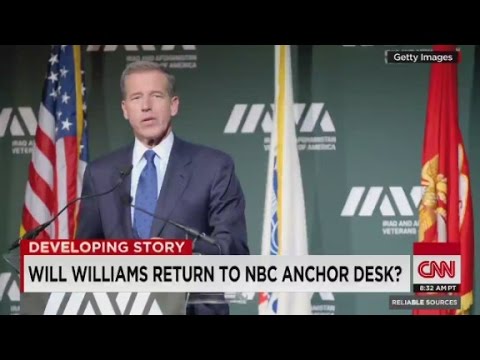

NBC News anchor Brian Williams got everyone to look at him when he told his dramatic tale of being in a helicopter that got hit by rocket fire in Iraq in 2003. Now he’s probably wishing he had stuck to serving his subject.

The irony, of course, is that by falsely inserting himself into the helicopter story, Williams is now at the center of a far bigger journalism ethics story, where he surely would rather not be.

One way to understand how one of the most respected broadcast journalists around could be on the verge of losing his anchorman’s chair is to see it as a logical outcome of tendencies that have been developing in broadcast news for decades.

Our man on the scene

TV news is predicated on the “stand-up” – the videographic version of the byline in print journalism. It’s a way for reporters to show viewers that they are on the scene, getting the news first-hand.

Such footage becomes more impressive when we see the reporter in a helmet and combat fatigues. Message: Our man in Vietnam or Iraq or Afghanistan or whatever the current hotspot is not just bearing witness to the dangers of war; he is facing those dangers himself and he’s doing it for our sake, so that we may be informed. We are supposed to be suitably impressed by his bravery and grateful for it.

From there, it is but a short step to reporters taking an active role in the events they’re covering, as CNN’s Anderson Cooper did when he whisked an injured boy to safety and as Dr. Sanjay Gupta did when he treated survivors after the 2010 earthquake in Haiti.

When I see such spectacles, I picture sports reporters racing from press box to locker room, suiting up and running out onto the field. But while traditionalists like me grumble about this kind of grandstanding, audiences apparently approve. Detached coverage of human suffering can come across as unfeeling, even exploitive. Fans want Cooper et al. to share and articulate their horror or their sorrow and, if needed, become Good Samaritans.

As often as practicable, therefore, today’s managing editors send their reporters out of the studio and into the field, preferably with bombs bursting in air or victims desperate for help. Thus have suited desk jockeys morphed into action heroes, preferably ones with well-toned muscles bulging out of tight T-shirts.

Almost famous

In such an environment, one can see where Williams was desperate to have a dramatic moment of his own. Alas, being in a helicopter that arrived on the scene after another helicopter had been crippled by rocket fire was the closest he’d come. And so his story changed from reporting on the wounded aircraft, as he did in 2003, to claiming he’d been on board when he talked about it 10 years later.

Perfectly understandable, right? Think of how much better my stories would be if I pretended I had witnessed historic events that I almost witnessed. I was going to go to Woodstock in 1969, but my parents wouldn’t let me. I was in Northern California at the time of the 1989 earthquake, but I was 120 miles east of the Bay Area and heard about the quake from sportscasters Al Michaels and Tim McCarver. I was in Ukraine in 2013, but I left before the revolution.

The soldiers who were on that mission in Iraq weren’t so forgiving. When they called his bluff, Williams said he “made a mistake.” His defenders note that memory plays tricks on us all. His far more numerous detractors find it hard to see how one could “conflate” – Williams’ word – a life-and-death situation with a non-life-threatening experience. In a time when journalists are increasingly a part of the story they’re covering, are the likes of Williams tempted to aggrandize in order to enhance their image?

Ethical lapses

At this writing, more than 1,200 readers have posted comments on the New York Times’ latest dispatch on the scandal. Some are cynics who can’t understand why anyone expects integrity from journalists. Some can’t understand why such a fuss is being made over a journalist when our politicians lie all the time. And some, still looking for the next Uncle Walter (Cronkite, that is), are heartbroken that a trusted journalist has proved himself untrustworthy. They’re through with Williams and they’re through with television news.

Williams’ apology, meanwhile, is taking its place among so many others we have heard from public figures who always seem to stop well short of admitting that their lapse was an ethical one rather than an honest “gaffe.”

Clearly, the public has had its fill of “misspeaking” and “conflating” and “misremembering.” If Williams were to acknowledge that he lied and to explain why he lied, it might go far better for him.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Read the original article.

Russell Frank is Associate Professor at Pennsylvania State University

—–

Related video added by Juan Cole:

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved