By Kevin Trenberth | National Center for Atmospheric Research | (The Conversation)

As first glance, asking whether global warming results in more snow may seem like a silly question because obviously, if it gets warm enough, there is no snow. Consequently, deniers of climate change have used recent snow dumps to cast doubt on a warming climate from human influences. Yet they could not be more wrong.

To understand the connection, we need to look at what conditions make for the heaviest snowfalls. Then, we can look at how climate change is affecting those conditions, especially temperatures in the atmosphere and oceans, during winters. Studying these factors reveals that there is a higher chance of heavy snow storms in North America but the length of the snow season is already shrinking due to global warming.

Goldilocks temperatures

There is a saying that it can be “too cold to snow”! Of course, this is a myth but it has a basis in fact because the atmosphere gets freeze dried when it is very cold. That’s because the amount of moisture the atmosphere can hold depends very strongly on temperature. Under cold conditions, the snow is likely to consist of very small crystals and sometimes is very light and fluffy and like “diamond dust”.

By contrast, the heaviest snowfalls occur with surface temperatures from about 28°F to 32°F – just below the freezing point. Of course, once it gets much above freezing point, the snow turns to rain. So there is a “Goldilocks” set of conditions that are just right to result in a super snow storm. And these conditions are becoming more likely in mid-winter because of human-induced climate change.

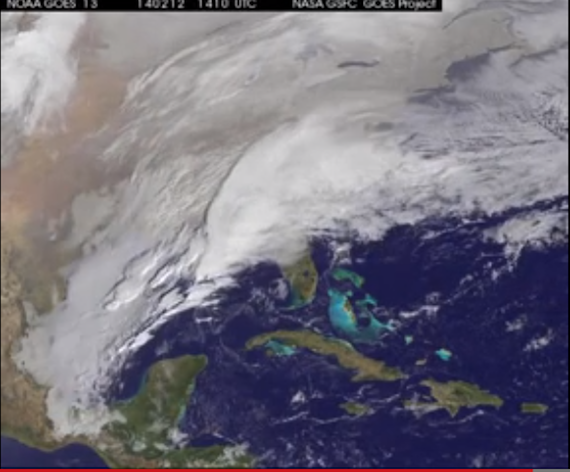

NASA Animation of GOES Satellite view of Feb. 2014 Snowstorm over USA

The physics behind this phenomenon is governed by a basic law that tells us the maximum amount of moisture in the atmosphere increases exponentially with temperature – that is, the warmer the atmosphere, the more moisture the air can hold and thus, the more potential for precipitation.

For most conditions at sea level, there’s a rule of thumb that says the atmosphere can hold 4% more moisture per one degree Fahrenheit increase in temperature. Some complications come in as the ice phase enters, but we set those aside for now. That translates into a big difference in moisture across temperature differences: At 50°F (10°C) the water-holding capacity of air is double that at 32°F (0°C) and at 14°F (-10°C) the value is only 24% that at 50°F.

More moisture

In fact, this relationship is fundamental to why it rains (or snows).

When a parcel of air containing water vapor is lifted, it moves into lower pressure, expands and cools. At some point, it can no longer hold as much moisture and so the moisture condenses into a cloud and ultimately forms rain or snow. The lifting of air comes mostly from storms, especially in warm fronts, as warm air moves over cooler air, or cold fronts, as cold air pushes under warmer air.

In all storms, the main source of precipitation is the moisture already in the atmosphere at the start of the storm. This moisture, as water vapor, is gathered by the storm winds, brought into the storm, concentrated and precipitated out. Accordingly, if there is more moisture in the environment, it rains (or snows) harder.

How does this play out when temperatures are below freezing? Temperatures in the Goldilocks range of between about 28°F and 32°F, accompanied by moisture, mean more snow: indeed, the amount of snowfall at 32°F would be at least double that at 14°F. It could be much more because the warm moist buoyant air may also contribute to intensification of the storm itself.

Recent winter storms and climate change

Extra-tropical storms in winter form and develop on differences in temperature, which are greatest between continents and adjacent oceans.

In winter, the cold dry air over North America forms a sharp contrast with the relatively warm moist air over the Gulf Stream and the North Atlantic. A cold front leads the southern outbreak of cold air while a warm front leads the warm moist air heading northwards as it rises upwards and produces precipitation within the storm.

The environment in which all storms form is now different than it was just 30 or 40 years ago because of global warming. Changes in atmospheric composition from human activities have increased carbon dioxide and other heat-trapping greenhouse gases, with carbon dioxide level increasing by over 40% since about 1900 mainly from burning fossil fuels.

The resulting energy imbalance warms our planet. And over 90% of the heat has gone into the oceans. In addition to higher sea levels – by over 2.5 inches since 1993 – global sea surface temperatures (SSTs) have risen by 1°F since about 1970.

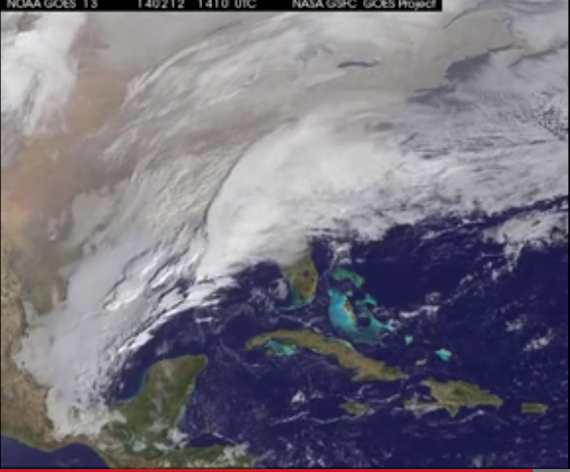

NOAA

So the memory of global warming is mainly in the oceans. On average the air above the oceans is warmer by more than 1°F and moister by 5% since the 1970s from global warming. In the North Atlantic, there has been additional warming and surface sea temperatures are over 2°F above a 1981-2010 average (which includes a global warming component) over a huge expanse extending more than 1000 miles from the coast of North America. (see graphic, above). Some of this extra warmth may have arisen from the absence of much hurricane activity in the Atlantic this past summer.

In February 5-6, 2010 a snow “bomb” occurred and led to what was referred to at the time as “Snowmaggedon,” which was used by several conservative Senators to mock global warming and Al Gore. Yet it was winter and there was plenty of cold continental air. There was a storm in the right place. And there were unusually high surface sea temperatures in the subtropical Atlantic Ocean – up to 3°F (1.5°C) above normal – which led to extraordinary amounts of moisture being fed into the storm. And it resulted in exceptional snow amounts in the Washington DC area.

NASA/NOAA

Earlier this week, between January 26-28, 2015, the area targeted by the latest winter storm, called Juno by some, was a bit further north. The developing storm was in just the right position to tap into the high moisture over the ocean and develop as it experienced the sharp contrast between the continent and the relatively warm ocean.

Over three feet of snow fell in some areas, blizzard conditions were experienced in New England, and heavy seas and erosion occurred in coastal regions in association with the higher sea levels associated with global warming.

Going forward, in mid winter, climate change means that snowfalls will increase because the atmosphere can hold 4% more moisture for every 1°F increase in temperature. So as long as it does not warm above freezing, the result is a greater dump of snow.

In contrast, at the beginning and end of winter, it warms enough that it is more likely to rain, so the total winter snowfall does not increase. Observations of snow cover for the northern hemisphere indeed show slight increases in mid-winter (December-February) but huge losses in the spring (see snow cover figure above.) This is all part of a trend to much heavier precipitation in the United States (see figure below), especially in the northeast.

US National Climate Assessment

Put another way: whether warming causes more or less precipitation varies by region, but it changes the balance between snow and rain. As long as it stays below freezing, the snow dumps are bigger, but the snow season shrinks at both ends of winter. So more time is spent raining: skiers in some regions benefit in mid-winter but with a shorter ski season.

Because the increased moisture in the storm can also feedback and amplify the storm itself, the extra snow can easily be order 10% or more from the climate change component.

See also:

Kevin Trenberth

Trenberth, K. E., 2011: Changes in precipitation with climate change. Climate Research, 47, 123-138, doi:10.3354/cr00953. [PDF]There is a sharp increase in one-day precipitation extremes during the October to March cold season.

National Climate Assessment data say the same thing.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Read the original article.

Kevin Trenberth is Distinguished Senior Scientist at National Center for Atmospheric Research

Via The Conversation

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved