By Adam H. Becker | (Informed Comment)

In their sanctimonious showboating ISIS has trashed the ruins of ancient Assyria and this is a loss for world cultural heritage and more so for Iraqis and whatever national culture will exist whenever the political situation finally becomes stable. However, Assyrian Christians, who themselves have suffered kidnapping and murder at the hands of ISIS criminals, may experience this as an even deeper cut. In fact, the ISIS assault on the archeological remains of northern Mesopotamia and the concomitant violence perpetrated against the region’s ethno-religious diversity merges in the suffering of the Assyrian Christians. For this community in particular identifies the sites disfigured by ISIS, such as the Nergal Gate in Nineveh, and the artifacts smashed in the Mosul Museum as the glorious remains of their eponymous forbearers.

The Assyrians are an ethnoreligious community who in the early twentieth century lived primarily in the region of what is now southeastern Turkey, northern Iraq, and northwestern Iran. They are part of a broader Syriac Christian tradition, which includes the Syrian Orthodox and the Maronites, as well as several other smaller churches. Syriac is a dialect of Aramaic attested first in the second century in Edessa (modern Urfa in Turkey). It came to function, as Latin did for the Catholic Church, as a language of liturgy and intellectual engagement, even while members of the Syriac churches increasingly became speakers of Arabic, Neo-Aramaic, and various other languages.

Historically the Assyrians belonged to the Church of the East, a separate ecclesiastical entity deriving from the Christological disputes of the fifth century, although Christianity itself arrived in northern Mesopotamia by the early third century. In Western sources even up to the present they are commonly referred to as Nestorians, after Nestorius the supposed founder of their “heresy.” By the time of the Arab conquest in the mid seventh century the church extended its hierarchy through central Iraq down into southern Iran and the Persian Gulf, and its successful proselytism had already begun east into Central Asia, where Christianity would most famously prove attractive to the Mongols centuries later (Kublai Khan’s mother was a “Nestorian” Christian).

“The cover of Yoshiya Amrikhas’s book of poetry, Tpaqta b-yema (“The Meeting with Mother”), published in Tehran in 1965.”

With the exception of communities in south India, by the nineteenth century the Church of the East had shrunk, and the majority of those members in northern Iraq, for example around Mosul, had joined the Uniate Catholic church, commonly known today as the Chaldeans. Old Church membership persisted mostly among two groups: inhabitants of villages on the plains west of Lake Urmia (today in Iran) and semi-nomadic pastoralists in the rugged mountains of Hakkari. The latter lived in a complex tribal system similar to that of neighboring Kurds. The patriarch of the church lived at Qudshannis (modern Hakkari city) as a kind of pan-tribal chief who received respect and support even from his flock across the frontier in Qajar Iran. The mountain tribes began to suffer violent onslaughts in the 1840s from Kurdish chiefs such as Badr Khan Bey, who attempted to create his own realm in his refractory relationship with the Ottoman authorities.

Violence in the broader region of eastern Anatolia and northern Mesopotamia east to Lake Urmia increased into the twentieth century. This was the time of the well known massacres of Armenians, culminating in the Armenian genocide, an event which included the murder and expulsion of a large number of Syriac Christians from what is now Turkey. The mountain tribes of Hakkari were expelled from Turkey finally in the 1920s, and many Assyrians settled in various cities and camps in Mandate Iraq. In 1933 some fled to Syria after the Simele massacre, which was the result of violence between Assyrians and Kurds in the fledgling state of Iraq. In recent weeks it is these same communities in Hassake, double exiles by descent – first from Turkey and then from Iraq – that have endured ISIS kidnappings, whereas it is the older Christian population north and east of Mosul who have often fled since the fall of the city and its environs to ISIS (The Monastery of Mar Behnam recently bombed by ISIS is a Syriac Catholic complex with a deep Medieval pedigree and is–or perhaps was–the location of a very rare thirteenth-century Old Turkic inscription).

After the violence and expulsion of WWI and the genocide Assyrians developed a staunch cultural nationalism, some even demanding a separate Assyrian state. Many of these national ideas had been developing since the nineteenth century, particularly under the influence of American and European missionaries. The very name Assyrian itself derives from a nationalist retrieval of the ancient Assyrian past. Whereas there is on occasion some interest in ancient Assyria in classical Syriac sources — this is no surprize because there was always an awareness that the area around Mosul was once the mighty empire known from the Bible — traditionally Assyrian Christians were known until the twentieth century primarily as “Syrians” or “Nestorians” or by whatever their tribe or village of origin was. In the context of their ongoing interactions with Western missionaries and orientalists — sometimes one in the same — these “Syrians” began to call themselves Assyrians. This identity then proliferated in the 1920s in diasporic settings around the world: Chicago, New York, Baghdad, South India, and Marseille, among other places. This cultural retrieval eventually resulted in the formal renaming of the church the Assyrian Church of the East and also in a new appreciation for ancient Assyrian cultural forms. Today it is common for Assyrian churches to borrow architectural motifs from classical Assyrian exemplars, such as the Nergal Gate of Nineveh, while for some time now certain ancient Assyrian names such as Sargon and Ashur have been revived. The winged bulls or lions with human faces recognizable to anyone who has visited the British Museum or the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York are reproduced in Assyrian media from children’s books to dating websites. It is the same creatures whose faces have been recently knocked off of the Nergal Gate by ISIS.

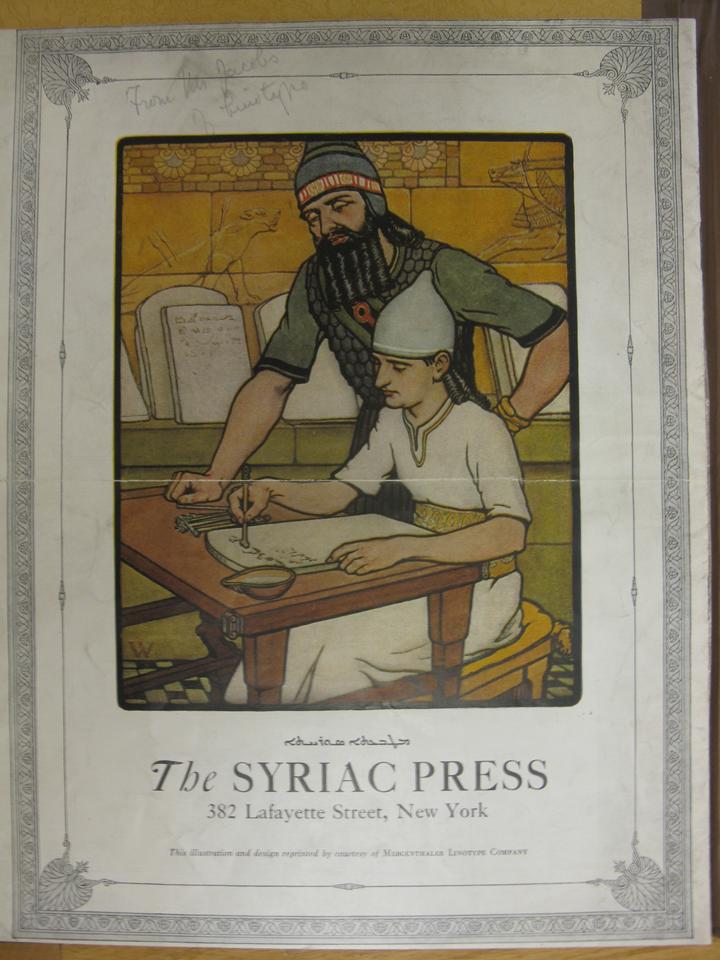

“An advertisement for the Syriac Press in New York founded in New York in 1920 by Assyrian Samuel A. Jacobs (not long before Jacobs became the personal typesetter of ee cummings).”

This identity has helped connect Assyrians as they have been dispersed further around the world, but it has also contributed to ongoing divisions within the Syriac communities. As a greater Assyrian identity developed so broader claims were made such that today some Assyrian nationalists will argue that all members of the Syriac churches are originally Assyrians even if they are not aware of it. There have also developed counter ethnicities (and corresponding counter histories): some Christians of the Syriac heritage identify themselves as Arameans, and in Sweden there are even competing soccer clubs with different ethnic associations (Syrianska and Assyriska). Attempts have been made repeatedly to overcome these divisions, most recently in autonomous Kurdistan among the inclusively hyphenated “Chaldo-Assyrian Syriacs.” Unfortunately the terrible adversities Syriac Christians have met in the modern history of the Middle East have not often served to bring them together for their own collective political benefit.

Adam H. Becker is Associate Professor in Religious Studies and Classics at New York University and author most recently of Revival and Awakening: American Evangelical Missionaries in Iran and the Origins of Assyrian Nationalism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015)

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved