By JOSEPH RICHARD PREVILLE and JULIE POUCHER HARBIN for ISLAMiCommentary :

Carla Power

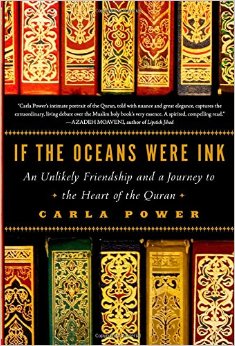

Great journalists invite us to be companions with them on their journeys to extraordinary places. Carla Power offers such an invitation in her new book, If the Oceans Were Ink: An Unlikely Friendship and a Journey to the Heart of the Quran (Holt Paperbacks, 2015).

The daughter of professors, Carla Power grew up in the Midwest and the Middle East & Asia, and later went back overseas to work as a foreign correspondent for Newsweek. Living in Iran, Afghanistan, India and Egypt shaped her global outlook and openness to the diversity of cultures and religions around the world.

Educated at Yale, Columbia, and Oxford, Power currently writes for Time and other publications. Her essays have appeared in a range of newspapers and magazines including The New York Times Magazine, The Guardian, Foreign Policy, O: The Oprah Magazine, Vogue and Glamour.

“As a journalist,” she writes, “I’d spent years framing Muslims as people who did things – built revolutions, founded political parties, fought, migrated, lobbied. I craved a better understanding of the faith driving these actions. I’d reported on how Muslim identity shapes a woman’s dress or a man’s career path, a village economy or a city skyline. Now I wanted to explore the beliefs behind that identity and to see how closely they matched my own.”

If the Oceans Were Ink is a beautiful story about how the sacred words of the Quran can bring two people together in study, understanding, and joyful friendship. Carla Power discusses her new book in this interview.

How did you choose the title of your book? Does it hold special meaning for you?

It’s from the Quran: “If all the trees in the earth were pens, and the ocean, with seven more seas to help it, were ink.” Allah’s words would not be exhausted. I chose it not just for its beauty, but because I like its message of limitless words — fitting, I thought, for a book about a year-long conversation between friends!

How did you come to meet Sheikh Mohammed Akram Nadwi? Was he the first person to teach you the Quran? How did his teachings inspire you?

The Sheikh and I were colleagues at a think-tank in Oxford more than twenty years ago, when we were both in our mid-twenties. We worked together on an atlas on the spread of Islam in South Asia. I had read bits of the Quran in college and grad school, but it was only with the Sheikh that I was able to bore down into parsing crucial verses.

I wanted to try to understand how he read it, as both a believer, and as a classically-trained Islamic scholar. My real interest was not in doing an exegesis, but in watching how the text shaped his life and worldview on issues, whether gender or migration, or sex or the Islamic State.

Your book description says you engaged in debates with the Sheikh “at cafes, family gatherings, and packed lecture halls, conversations filled with both good humor and powerful insights.” Was your Quranic education with the Sheikh mostly outside the classroom? Did you travel – “go on tour” – with the Sheikh and where did you go? What were some of the highlights?

The Sheikh and I are sitting outside the Oxford Kebab House, the Persian-owned café in North Oxford where we often met for lessons. (photo courtesy Carla Power)

Writing the book, I was a bit like the Sheikh’s groupie: In addition to meeting him for one-on-one discussions of the Quran at Oxford cafes and kebab houses, I trailed him around the United Kingdom for his lectures and classes. On weekends, he teaches 8 hours a day, Saturday and Sunday. It was fascinating seeing the wide range of people that gathered at his lectures. One time a fiercely political and slightly menacing crowd came to hear him speak on jihad and sharia in East London.

When he lectured on jurisprudence related to women, the teenage girls were desperate to ask him about whether they could wear nail polish and pluck their eyebrows. His regular Quran classes in Cambridge were full of young professionals and families, who posed questions on everything from hellfire to the Arab Spring.

Part of the book’s aim — combatting flattened stereotypes of Islam — meant portraying him as a rounded human being. So I’d shadow him doing other things, too — heading for the gym, going to buy sewing supplies with his wife, letting his daughter go shopping in the Oxford mall…

My favorite trip was following him back to his village in Uttar Pradesh, India, where I stayed in his parents’ home, and I gave a lecture to an all-male crowd at a madrasa he’d built there. We also spent a few days in his beloved Lucknow, visiting his alma mater, the famous madrasa Nadwat-al-Ulama, and taking a roadtrip to see his old friends, and his old haunts – including where he used to go shooting quail on Friday mornings. Seeing the Sheikh’s highly conservative familial home, was a reminder of just how far he had come, from a tiny village to being a world-class scholar, and champion of Muslim women’s rights.

Perhaps my favorite outing in Britain was a day at Heathrow Airport, seeing him and a group of students off to Mecca and Medina on pilgrimage. Standing at Heathrow, it was amazing to witness mix of the sacred and logistical — of the students discussing whether their baggage allowances would allow for bringing back water from the famous Zamzam well in Mecca, or watching the Sheikh recite a poem about pilgrimage amid the bustle of Terminal 5.

As a non-Muslim, I couldn’t get a visa to go with them, but just by being there, and by trying to recreate their trip through interviews, I got to witness how a pilgrimage to Mecca, while at its heart is a spiritual journey, is also a matter of making sure the Ramada Inn has your reservations!

Some say the Quran preaches violence, not peace, and oppression of women, not respect. How would you respond to these “experts” and the people that believe them?

I think there’s great confusion in the Western media between what some Muslims do — or in the case of the oppression of women, how many Muslim-majority societies function — and what the Quran and hadith say. I would refer them to what Sheikh Akram always stressed: context! context! context!

In his view, the verses that jihadis and Islamophobes alike love to cite about killing infidels refer to very specific moments in early Islamic history. They are to be read through the prism of the moment they came down to the Prophet Muhammad, according to the Sheikh, and are not blanket injunctions.

In the case of Islam’s treatment of women, the Sheikh believes many modern Muslims have forgotten the basic rights Islam gives them. When societies feel scared and weak — whether because of political or economic enfeeblement — they don’t give women and minorities justice.

Why is the Quran so controversial? Is it more controversial than say the Bible or the Torah?

Both the Old Testament — and Christian history itself — contain explicit examples of religiously sanctioned violence. But the Quran is uniquely controversial today because of the way it’s being used by a tiny minority of the world’s 1.6 billion Muslims — as providing a religious justification for violence. Extremist readings of Islamic tradition — along with scores of other reasons, including the scars of imperial meddling in the region, both past and present — are helping fuel the conflicts shaping the world today.

How much were non-Muslims’ perceptions of the Quran informed by 9/11, terrorism, and the “clash of

civilizations” rhetoric that followed?

The loudest voices, both from within Islam and outside of it, tend to be the extremist ones. The men dropping bombs or beheading make news, so it goes that their interpretations of the Quran gain traction. The Californian mystic poet,the Iranian quietist, the French human rights activist — we don’t hear their interpretations of the Quran.

While ultra-conservatives have occasionally frowned on the Sheikh taking one-on-one questions from women students at breaks in his lectures, he makes himself readily accessible to all his students. (Photo credit: Cambridge Islamic College)

While ultra-conservatives have occasionally frowned on the Sheikh taking one-on-one questions from women students at breaks in his lectures, he makes himself readily accessible to all his students. (Photo credit: Cambridge Islamic College)

What did you learn from Sheikh Akram about the hadith?

As blueprints for the Prophet’s Sunna, or morals and habits, the hadith are central to Sheikh Akram’s life. It was fascinating to see someone try to live in the way of the prophet from a row-house in Oxford — taking his cues from hadith on everything from how to eat to how to greet guests, treat his wife, or raise his six daughters.

With a wife and six daughters he must have learned a lot about women. What is the Sheikh’s view of the role of women within Islam? Do his views derive from his interpretation of the Quran or his interpretation of the hadith? Or, are his views cultural?

He tries as much as possible to adhere to textual, rather than cultural interpretations. Indeed, when he’s pointed out that practices like the niqab or, for men, skull-caps worn for prayer, are cultural rather than textual, he’s ruffled feathers in various Muslim congregations! That said, I’m aware that the Sheikh’s adab, or gentle etiquette, means that he’s very sensitive to trying to force change on a community, just because he knows many of their practices aren’t Islamic, but cultural.

I saw that first-hand when I followed him to his home village, Jamdahan. Though he’s been seen as the Muslim community’s great religious authority there since he was a teenager, he still is careful not to disturb the status quo. Here’s a man who’s literally written the book on women’s freedom to attend worship and study in mosques and madrasas, and yet, when I spoke in his madrasa, I was the only woman there! All the women of the village remained in purdah! (‘Purdah’ is the custom of Muslim and Hindu women being screened from men who aren’t close relations, either by a veil, or by keeping separate, all-female quarters in a household.)

How much are religious scholars’ views on social issues and law informed by the Quran, the hadith, and the culture in which they preach?

That’s very hard to answer: it varies from scholar to scholar and culture to culture! What I can say is that more and more Muslims, with better literacy and education than their grandparents often had, are going back to the basic texts, and working to strip away the cultural layers that have accumulated around them. That process of challenging the old authorities has produced a whole range of new voices, from violent extremists to feminists. It’s a time of ferment, as a new generation of Muslims seek to interpret classical texts.

What is the importance of Sheikh Akram’s book, Al-Muhaddithat: The Women Scholars in Islam (2013)? Is it influential outside of scholarly circles?

Al-Muhaddithat is the first volume of a 40-volume biographical dictionary of Muslim women scholars. When the Sheikh began work on it, he figured it would be a slim pamphlet — a matter of 30 or 40 women since the 7th century. Now, his findings number more than 9,000 women. But it’s not just about numbers: he’s found women were riding camelback on lecture tours throughout Arabia, who were issuing their own fatwas, who taught caliphs and male scholars. His work — most of which, sadly, remains in his computer hard-drive to this day — not only suggests the rights and freedoms earlier generations of women enjoyed. It also sheds new light on how much more inclusive Islamic scholarship was than it often is today.

On both counts, it’s crucial, and needs wide dissemination! Currently, his students are trying to come up with the money to have it published or to persuade him to publish it online. It is known outside academic circles. Increasingly, the Sheikh is being asked to speak by Muslim women’s groups around the world.

How has your book been received and what’s your next project?

I’ve been delighted by the reception, particularly from book clubs and on university campuses. It came out at around the same time as some headline-grabbing treatments of Islam — ones whose takes were polar opposites to my own. It’s a quieter book, but one with, I hope, some staying power. I’m still deciding on what my next project will be. It will either be Islam-related, or a biography of an amazing New Yorker who championed migrant rights.

One of my favorite childhood games involved guessing the thoughts of the veiled women I saw in busy streets in Muslim cities. Here I’m standing in a crowded bazaar in Kabul, Afghanistan, and a curious burqaed lady turns toward the camera as she passes by. Later, as a journalist, I had returned to Kabul and wore a burqa in order to remain undetected as a foreigner, and I reported on life under Taliban rule. (photo courtesy Carla Power)

What was it like to grow up partly overseas and how did it affect your career decisions ?

A childhood spent shuttling between St. Louis and Muslim countries put both American and foreign cultures in relief. I keep thinking of the old quote from Kipling, which goes something like: “What do they know of England, if only England know?”

I’m also conscious that being in Afghanistan, Egypt and Iran in the 1970s was to witness the region at a crucial time. Even as educated Americans, interested in the cultures we found ourselves, and indignant at the despotic repressions we witnessed in places like Iran, my parents were clueless of the magnitude of the tensions roiling beneath the surfaces of society.

We knew something was wrong with the Shah’s go-go modernization drive, but vastly underestimated that Islam, harnessed to public anger, could tow a revolution.

In Kabul in 1978, we rolled out of a Little League game into a line of tanks — which proved to be the leftist coup that toppled Afghanistan’s king, paving the way for Soviet invasion. That invasion, like the Iranian Revolution, changed the West’s relationship to Islam.

Where the Islamic societies of my father’s generation had been relatively distant and self- contained, various events — the Iranian Revolution, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, and mass Muslim migration — mean that the Islamic world is no longer ‘out there.’ It’s us; we’re them.

Ever since I studied Edward Said’s Orientalism as an undergrad, I’ve been eager to investigate the forces that go into how the Western world defines the Islamic one.

How has your Quranic journey changed your life? Would you recommend this journey to other people?

Aside from motherhood, it was the most profound journey I’ve been on. It was not the text itself that I responded to — I found the Quran itself a real challenge. The best thing about the journey was getting the chance to have an extended conversation with someone so different from myself.

Here I was, an American feminist, the daughter of a lapsed Jew and a non-practicing Quaker, with carte blanche to ask a conservative madrasa trained Indian male Muslim any question under the sun.

Joseph Richard Preville is Assistant Professor of English at Alfaisal University in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. His work has appeared in The Christian Science Monitor, San Francisco Chronicle, Harvard Divinity Bulletin, Tikkun, The Jerusalem Post, Muscat Daily, Saudi Gazette, and Turkey Agenda. He is also a regular contributor to ISLAMiCommentary.

Julie Poucher Harbin is Editor of ISLAMiCommentary.

—

Via IslamiCommentary

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved