By: Anna Kokko | (Ma’an News Agency) | – –

ANATA (Ma’an) — In the northeastern corner of the Palestinian village of Anata, between the separation wall and Israel’s illegal settlement of Pisgat Ze’ev, a crowd of about a hundred people has gathered for a celebration.

On a small stage, a group of twenty foreign activists claps and sings about rebuilding and resistance. At the end of the song, a key is handed to a Palestinian man, Hajaj Fhadad.

Soon after, Fhadad’s extended family of 11 children and two other adults start carrying their furniture into a house that did not exist two weeks ago.

Outside the property, wind is humming through the newly planted orange and lemon trees, gifts from the volunteers of the Israeli Committee Against House Demolitions (ICAHD), who built the home with the help of Palestinian construction workers.

Just a couple of months before, the Fhadad family did not have much to celebrate. Their previous house, under a demolition order from the Israeli authorities, was destroyed twice.

In fact, it was the father of the family, Hajaj, who took the light hammer into his own hands each time the Israeli bulldozers came. By destroying the home himself, he could avoid paying for the Israeli municipal workers who were sent to do the job.

For Hajaj, it was also an attempt to trick the authorities; by destroying only parts of the house, his family could somehow continue living in other parts of it, albeit in harsh conditions.

Fighting ethnic cleansing

The Fhadad family are not the only Palestinians who have seen their home in ruins in the seam zone northeast of Jerusalem.

According to the Applied Research Institute in Jerusalem (ARIJ), at least 14 houses in the village of Anata have been demolished since 2004, including one kindergarten. As of 2007, the town had a population of close to 1,900 residents.

Jeff Halper from ICAHD estimates that about 60 of the village’s houses have been destroyed since the beginning of the Israeli occupation in 1967.

The total number of houses destroyed in the Palestinian territories during the same period is 46,000, the organization reports.

“It is a clear policy of ethnic cleansing, and of Judaizing the country,” Halper says.

Palestinian building and planning is highly restricted in Area C, around 60 percent of the West Bank under complete Israeli security and administrative control following the Oslo Accords.

Each year, Israel only approves a handful of Palestinian building permits in Area C, while the majority of Israel’s illegal settlements are located in same area.

Palestinian houses built without permission face the immediate threat of demolition.

Having emigrated from the United States to Israel in 1973, Halper co-founded ICAHD in 1997 to protest these systematic demolitions.

While the organization has rebuilt a total of 189 houses all over the West Bank and Israel, their annual reconstruction summer camp has always been held in Anata, now for the thirteenth time.

The division of labor is clear: The local committee in Anata decides which of the villagers’ houses needs to be rebuilt, while ICAHD gathers the participants as well as the funds for the materials and salaries of Palestinian construction specialists.

A large part of the funding comes from the campers, who pay $1,700 dollars for their participation.

“It isn’t Israelis helping poor Palestinians. Instead, we’re resisting together,” Halper says.

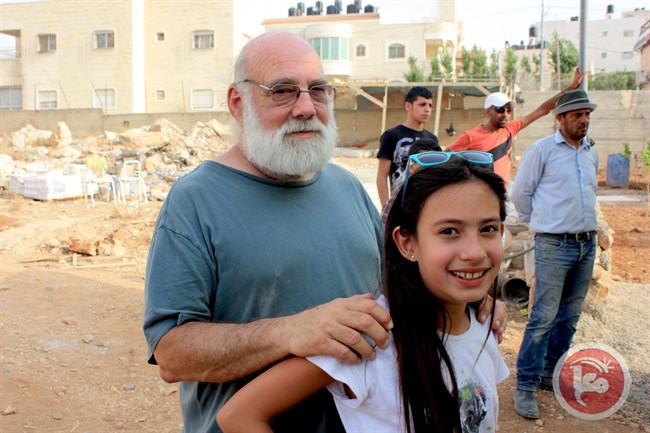

Jeff Halper, co-founder of ICAHD, at the dedication ceremony on Sunday. (MaanImages/Anna Kokko)

Demolition of a society

In practice, however, the camp participants are mostly foreign activists. Coming from countries such as Australia, Germany, and the United Kingdom, some are in their early twenties while others have already retired.

One of the elderly participants, 67-year-old Gordon Pedrow from the United States, says the camp was some of the hardest work he has ever done.

“We’re all office workers here,” he says. “The camp is real physical work in a hot environment.”

In addition to the reconstruction work, the campers made field visits to other Palestinian cities and had lectures from local human rights organizations and activists. Pedrow says that the two weeks were “a tremendous experience” but also emotionally draining.

“This opened my eyes to a systematic demolition of not only houses but of a whole society,” the former city manager says.

Fhadad family in front of their new house. (MaanImages/Anna Kokko)

Although there are newcomers as well, many of the participants have been to the camps more than once. All have a long-time interest in the Palestinian cause, but for some, the road to activism has not been smooth.

Such is the case of Miika Malinen, for example. Originally from Finland, Malinen lived in Bethlehem and West Jerusalem for 15 years of his childhood while his parents worked as Christian missionaries. At the dinner table, Israel was never criticized.

“We lived in a very nice, international bubble, not wanting to grasp what was happening around us,” he recalls.

After a long process of studying and reading reports, Malinen flew back to the occupied Palestinian territories to do field research. Participating in the rebuilding camp was a years-long dream.

“Meeting the (Palestinian) people here touches you in a different way than reading the reports,” he says.

Destruction in 15 minutes

A few kilometers away from the construction site, the campers have stayed for the two weeks at the house of one of the Palestinian organizers.

Next to the house, ICAHD has left the ruins of one demolished house on display.

“I was rebuilding this house two or three times,” says Bruno Jantti, head of the Finnish branch of ICAHD.

He thinks that facing the rubble every day is a good reminder of the reality of the occupation.

“The result of our work can be destroyed in 15 minutes,” Jantti says. “The Palestinians here are living under constant uncertainty, never knowing when a demolition can happen.”

As one of the participants puts it, the newly built house is just “one small step towards ending the occupation.” But Jeff Halper, the head of ICAHD, sees an increase rather than an end of the Israeli practice of house demolitions.

“We see demolitions almost every day now. There is a lot of pressure especially in the Jordan Valley,” he says.

The director believes that large-scale destruction is awaiting also the Palestinian village of Susiya, which has gained international attention after the Israeli authorities ordered its demolition after the Islamic holy month of Ramadan.

“Israel feels that it has won, while the Palestinians are too fragmented to resist. Nobody is going to stop them,” Halper says.

Whether the Fhadad family can stay in their house long enough to see the citrus trees grow remains open, too. But at least on Sunday night, they had a new roof on top of their heads.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved