By David Shields | (Informed Comment) | – –

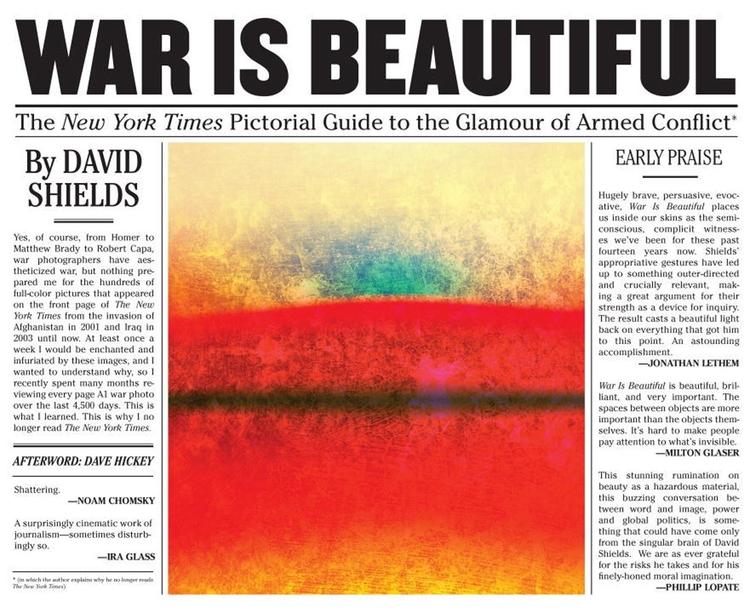

The following is an excerpt from War Is Beautiful by David Shields:

For decades, upon opening the New York Times every morning and contemplating the front page, I was entranced by the war photographs. My attraction to the photographs evolved into a mixture of rapture, bafflement, and repulsion. Over time I realized that these photos glorified war through an unrelenting parade of beautiful images whose function is to sanctify the accompanying descriptions of battle, death, destruction, and displacement. I didn’t completely trust my intuition, so over the last year I went back and reviewed New York Times front pages from the invasion of Afghanistan in 2001 until the present. When I gathered together hundreds and hundreds of images, I found my original take corroborated: the governing ethos was unmistakably one that glamorized war and the sacrifices made in the service of war.

The Times’s photographic aesthetic derives, in part, from the paper’s history. Patriarch and publisher Adolph Ochs bought the paper and transformed it into an institutional power. “All the news that’s fit to print.” “The paper of record.” Altough Ochs’s mother and father, who were German-Jewish, had each come to the United States in the 1840s to escape anti-Semitism, Adolph wold retain a sentimental attachment to Germany and the continuity of European civilization. Faced with a different form of anti-Semitism in the States, Ochs and the subsequent publisher, his son-in-law, Arthur Hays Sulzberger, made a conscious, self-protective decision to stave off any public perception that the Times was beholden to specifically Jewish interests.

In The Trust, Susan Tifft and Alex Jones explain the ramifications: “The Times’s reporting of Jewish persecution was remarkably thorough, and the paper often raised its voice forcefully in editorials, but crucial news stories were frequently buried inside the paper rather than highlighted on page one. . . . Like his late father-in-law [Adolph Ochs], he [Arthur Hays Sulzberger] did not want the Times to be viewed as a ‘Jewish Paper,’ but in his single-minded effort to achieve that end, he missed an opportunity to use the considerable power of the paper to focus a spotlight on one of the greatest crimes the world has ever known. The Times was hardly alone in downplaying news of the Final Solution. In the late 1930s and early 1940s, other major dailies . . . like the public at large, disbelieved reports of Jewish genocide in Europe or suspected that they were exaggerated in order to attract relief funds. But the Times was unique in one respect: as the preeminent newspaper in the country, with superior foreign reporting capabilities, it had much power to set the agenda for other journals, many of which took their cue from the Times’s front page. Had the Times highlighted Nazi atrocities against Jews, or simply not buried certain stories, the nation might have awakened to the horror far sooner than it did.”

Tifft and Jones’s evocation—of a quasi-government entity positioning itself so as not to antagonize the Roosevelt administration’s willful blindness to the situation of Jews in Europe—is predictive: even when taking an editorial position against particular government actions, the Times, though considered “liberal,” never strays far from a normative, centrist position. The center would never again not hold. The Times and the U.S. government use each other to instantiate their own authority. Throughout its history, the Times has produced exemplary war journalism, but it has done so by retaining a reciprocal relationship with the administration in power. The paper of record has become the paper of record by being so integrated with the highest levels of authority (James B. Reston simultaneously advising and editorializing in praise of JFK) that it knows precisely what truth the power wants told and then prints this truth as the first draft of history.

After U.S. troops left Iraq, former Times Baghdad bureau chief John F. Burns wrote in a Times war blog: “America, for all its mistakes—- including, as so many believe, the decision to invade in the first place—- will at least have the comfort of knowing that it did pretty much all it could do, within the limits of popular acceptance in blood and treasure, to open the way for a better Iraqi future.” President Lyndon Johnson said about Viet Nam, “I can’t fight this war without the support of the New York Times.” A Times war photograph is worth a thousand mirrors.

Art is an ordering of nature and artifact. The Times uses its front-page war photographs to convey that a chaotic world is ultimately under control, encased within amber. In so doing, the paper of record promotes its institutional power as protector of death-dealing democracy and curator of Western civilization. Who is culpable? We all are; our collective psyche and memory are inscribed in these photographs. Behind these sublime, destructive, illuminated images are hundreds of thousands of unobserved, anonymous war deaths; this book is witness to a graveyard of horrendous beauty.

David Shields’s most recent book is War is Beautiful (Powerhouse Books, Nov. 10, 2015). He is the internationally bestselling author of 20 books, including Reality Hunger (named one of the best books of 2010 by more than 30 publications), The Thing About Life Is That One Day You’ll Be Dead (New York Times bestseller), and Black Planet (finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award).

Book Credit: Text © David Shields from War Is Beautiful (PowerHouse Books, November 2015)

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved