By Charles Recknagel

| RFE/RL

Daniel Koehler is among a handful of people in the West who work with Islamist militants returning from Syria in an effort to reintegrate them into normal life.

A native of Germany, he works with such former fighters and their families in countries across Europe and in North America and has become intimately familiar with the power of jihadist ideologies to attract new recruits.

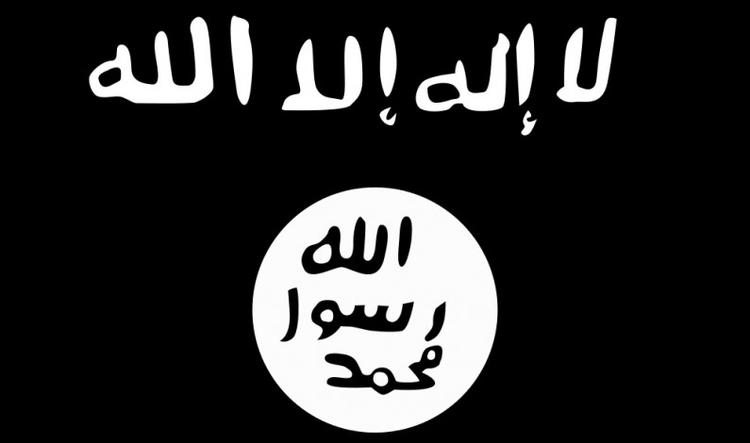

As the radical [so-called] Islamic State (IS) has become the world’s most notorious Islamist militant group, he and others in his field have watched it go far beyond what other such groups, including Al-Qaeda, were able to do in gaining followers worldwide.

Koehler notes that all such self-styled jihadist groups recruit new members by arguing that Islam is under attack by evil forces, that the faithful must fight back, and that, by joining the group, recruits will help build a new home for true Muslims.

“But Islamic State is actually fulfilling a lot of this narrative with deeds on the ground,” Koehler says. “They control a vast geographic territory, they really try to appear as a full-functioning, full-fledged state; and that, combined with the core narrative, shows to many who are attracted to Islamic State that they are actually the ones fulfilling all the promises that Al-Qaeda and other Islamist jihadist organizations have never been able to do in the past.”

It is a message that can appeal to individuals irrespective of their social or economic status because it gives them both a cause to believe in and a physical destination to go to. Or, in the case of radicalized individuals who choose to wage attacks in their home countries, it gives them something resembling a state to which they can declare their allegiance.

As head of the German Institute on Radicalization and De-radicalization Studies (GIRDS), Koehler has spoken with dozens of fighters returning from Syria and Iraq and found their individual motives are a mix of factors. They may be angry and frustrated with dysfunctional home situations and alienated by perceived racism and exclusion in their societies. At the same time, they may have a desire for adventure and want to help others they perceive to be in danger.

IS has proved particularly successful in reaching out to such people in part because it has adopted the same storytelling techniques for its narrative that Hollywood uses in creating epic films that appeal to mass audiences.

IS tells its story “in a way that mimics Western pop culture, Hollywood movies and video games, so that it is offering audio-visually what adolescents are very used to,” he says. The group has produced its own version of a video game, a feature-length documentary, short video clips for Twitter, and posted battlefield footage from Syria and Iraq, using social media as its distribution channel.

High Expectations

Some observers say that IS could ultimately discredit itself if it fails to live up to the high expectations its recruitment campaign creates.

IS spokesman Abu Mohammad al-Adnani declared in 2013 that the group’s goal was to establish an Islamic state that doesn’t recognize borders,” following the example of Islam’s founding conquerors.

But writing earlier this year in The Atlantic, journalist Graeme Wood noted that “with every month that it fails to expand, it resembles less the conquering state of the Prophet Muhammad than yet another Middle Eastern government failing to bring prosperity to its people.”

Still, the group’s narrative could prove resilient to battlefield defeats because it envisions that there will be reverses along the way to what it promises will be final victory.

The story line goes like this: IS fighters will win a resounding victory over unspecified forces in the north of Syria and the group, in fact, has already gone to some trouble to capture the town of Dabiq, the site where that battle is to take place. IS has even named its official magazine “Dabiq,” in honor of the anticipated battle.

But, the narrative continues, IS will later suffer a stunning defeat by forces coming from Khorasan — a historical region comprising parts of modern-day Iran, Afghanistan, and Central Asia. Afterward, just a few hundred surviving fighters will make a last stand in Jerusalem. And there, Jesus Christ, whom Islam regards as a prophet second only to Muhammad in importance, will come to lead them to the final triumph of Islam worldwide.

Fighting Back

By preparing its followers for both victories and setbacks, IS makes it hard for even a resounding defeat on the battlefield to dent its ideological appeal. But some observers believe the ideology can be defeated if Western and other societies make a greater effort to expose the reality of the organization to potential recruits.

Koehler believes that fighters returning from Iraq and Syria to their home countries could be essential to that effort. He says that most of those returning today are people who are traumatized by their experiences and disillusioned with IS, particularly its extreme brutality.

“Many foreign fighters who return are immensely disillusioned,” he says. “You just can imagine for yourself that if you would have joined [IS] and gone to Syria and Iraq, and you had liked it and found what you were looking for, there would be no reason to come back unless you were sent; and [IS] is currently not in a position to send back fighters on planned missions, they need fighters on the ground.”

He argues that the returning fighters can be the most effective voices in their community for discouraging others from following in their footsteps. Particularly, he adds, if their home countries offer the returnees a second chance and try to reintegrate them in society rather than jail them for having joined a militant group.

Such an approach is being tried in some northern European countries. City authorities in Aarhus, Denmark, have attracted global attention with a reintegration effort begun in 2013 that they credit with dramatically reducing the number of new IS recruits from the city.

Britain’s Guardian newspaper reported in November 2014 that 31 young men left the city for Syria during late 2012 and 2013. But in 2014, just one person did so.

The program in Aarhus has been criticized by some conservative political parties, including the anti-immigration Danish People’s Party, as “naïve” because of the risk city officials might not be able to identify returnees who remain radicalized. But proponents of the program, including the police, say intensive monitoring of the returnees minimizes that danger.

Via RFE/RL<

Copyright (c) 2015. RFE/RL, Inc. Reprinted with the permission of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, 1201 Connecticut Ave NW, Ste 400, Washington DC 20036.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved