By Hsain Ilahiane | (Informed Comment) | – –

Arabs and Muslims Made and Are Still Making America Great: One came on foot, one with camels, and one brought Apple products to us.

Arabs and Muslims have been under clouds of suspicion and scrutiny since recent mass shootings in Paris, France, and San Bernardino, California. Populist politicians such as Donald Trump, along with a chorus of fretful conservative radio talk show hosts and social media commentators, have declared open season on immigrants and have unleashed a relentless barrage of vitriolic attacks and scorn on Muslims, Syrian refugees, and Hispanics. In a series of chilling rants against all things Muslim, Donald Trump and his supporters have proposed halting Muslims and Syrian refugees from entering the U.S. ” The unsympathetic descriptions and images of Arabs and Muslims coupled with post-9/11 islamophobia and racism disingenuously exclude Muslims from belonging to the United States, purposefully dehumanize them, and misleadingly dismiss Arab and Muslim contributions to making America great. History tells us that Arabs and Muslims were and have been part and parcel of making America great since the arrival of European settlers to the shores of the Americas.

Accounts of three major figures who originate from Muslim North Africa and the Middle East are briefly profiled below; they embody the American experience, and changed America and the world. One came on foot with the Spanish conquistadores in the 16th century; one came with camels in the 19th century; and one co-founded Apple at the end of the 20th century. They are the Moroccan Estevan De Dorantes, explorer of the American Southwest; the Syrian Hadji Ali, the camel driver of the US Camel Corps in the American West; and the Syrian by descent Steven Jobs, the co-founder of Apple, respectively. The first two incarnated in some measure the beliefs of Manifest Destiny while the last one epitomized the tenets of the Californian Ideology.

Estevan De Dorantes: Moroccan-Spanish explorer and connector of the Old World and the Americas.

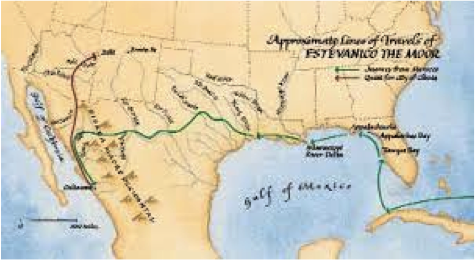

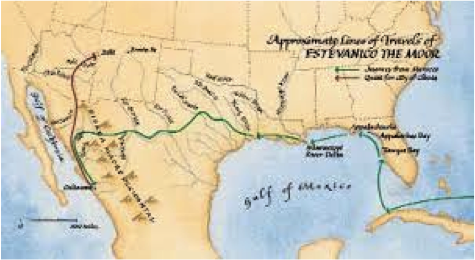

One of the most fascinating men in the history of the American Southwest was the Moroccan “slave” known as Estevan de Dorantes. Estevan was one of the four survivors of the Narváez Expedition, which sailed from Spain in 1527 with the objective of conquering Florida and the Gulf of Mexico. The survivors were stranded on the coast of the Gulf of Mexico and soon captured by Native Americans. After eight years of slavery, the expedition members escaped and traveled west, across western Texas, through the southwestern borderlands, and arrived in Cualiacán, Mexico, in the spring of 1536. Three years later, Estevan led the first Spanish expedition to Zuni lands and was the first Arab (or Berber or Black) Muslim and non-Native American to set foot in present day Arizona and New Mexico (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Map showing the approximate route of Estevan De Dorantes, 1527-1539. Source: http://www.princeton.edu/~bsu/images/Estevanico2.jpg

Despite Estevan’s role in Spain’s age of exploration and imperialism in the Americas, historical accounts are silent about him except to note that he was a slave who accompanied Fray Marcos De Niza on his travels through the American Southwest. Nevertheless, Estevan remains an important figure in the social history of Pueblo Indians, and indeed figures in a legend shared by the Zunis and Hopis. Dennis Slifer and Jim Duffield, in their book Kokopelli, suggest that a “connection between Zuni and Hopi is implied in the form that Kokopelli takes at the Hopi village of Hano. Here he appears as a big black man, known as Nepokwa’i, who carries a buckskin bag on his back. Even the kachina dolls of this figure are painted black. Nepokwa’i maybe based on the Moorish slave Estevan, who accompanied Fray Marcos De Niza’s expedition. Estevan was stoned to death at Zuni for molesting their women.” Additionally, Edmund Ladd, a Zuni anthropologist, wrote that Estevan “was one of the first to see the Mississippi River, the first to contact the pueblo people and the first to die at the hand of the native people—his place in history is as important as Viceroy Mendoza, Coronado, or Antonio Espejo.” (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Estevan Park, Tucson, Arizona. The park does not have a historic marker. Photograph by Hsain Ilahiane, 2016.

Hadji Ali, a.k.a. Hi Jolly and later as Philip Tedro: Syrian-American camel driver and connector of the American West.

The United States government experiment with establishing a camel corps began in 1855 when Jefferson Davis, then Secretary of War and later president of the Confederacy, commissioned seventy-five or so camels to be shipped from the Levant (Middle East) for military purposes and expansion in the American West. Hadji Ali arrived in the United States in 1856 as a camel driver in the Jefferson Davis’ Fort Tejon Camel Corps experiment. Hadji Ali, born in Syria in 1828 and a veteran of the French Army in Algeria, was the first camel driver to be hired by the US Army to train soldiers in the ways of the camel and to lead the US Camel Corps experiment in the deployment of camels for reconnaissance and transportation in the Southwest. Soldiers whom Hadji Ali was assigned to teach about camels could not pronounce “Hadji Ali,” and they changed it to “Hi Jolly.” The name of Hadji Ali is Arab. The title Hadji is an honorific title given to a devout Muslim who has successfully completed pilgrimage to Mecca, the Hajj. In other social contexts, it may also refer to an elder since it usually takes time to gather funds for travel to Mecca (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. A replica of Hi Jolly memorial and a display showing Hadji Ali in Arab dress and a herd of camels in the Municipal Center and Library, Quartzsite, Arizona. Photograph by Hsain Ilahiane, 2015.

In its early years of operation, the camel corps proved successful. It connected dispersed settlements, opened communications between Texas and California and transported military equipment and supplies throughout the new Western frontiers. However, with the eruption of the civil war and the lack of government funding the camel corps experiment ended. In 1864, some camels were sold in California and Texas; others escaped into the wild. In 1870, Hadji Ali was dismissed from the US Army and bought two camels and ran a freight route between the Colorado River and the mining towns of eastern Arizona. His freight service failed, and he released his camels into the desert. In 1880, he became a United States citizen and in 1885 he served in the US Army in the Arizona territory and worked with pack mules for Brigadier General George Crook during the Apache wars, particularly the Geronimo campaign.

After retirement from army service, Hadji Ali settled down in Quartzsite, Arizona, where he prospected in the area using a mule, and occasionally scouted for the U.S. government until his death in 1902. In 1935, the Arizona Highway Department dedicated a pyramid-shaped monument to Hadji Ali and the camel corps (see Figure 4). The monument dedication plaque reads:

The last camp of Hi Jolly, born somewhere in Syria about 1828 / Died at Quartzsite December 16, 1902 / Came to this country February 10, 1856 / Camel driver – packer – scout-over thirty years a faithful aid to the U.S. government. Arizona Highway Department, 1935.

In the course of time, camels and the legend of Hadji Ali entered the myth of the American West and have spawned several novels, movies, tales, songs, plays, and ghost stories. Today, the Hi Jolly cemetery is the most visited site in Quartzsite, and every January 10, the Quartzsite Chamber of Commerce hosts a festival in honor of the Syrian camel driver,“Camelmania: Hi Jolly Daze Parade.”

Figure 4. Hi Jolly tomb and memorial, Quartzsite, Arizona. Photograph by Hsain Ilahiane, 2015.

Steven Jobs: Syrian-German-American innovator and connector of the global village.

While Manifest Destiny provided America with a moral justification to control a continent and to create what Jefferson called “the empire of liberty,” the proponents of the Californian Ideology fused information technology with capitalism to create and connect a “global village” of liberty. The Californian Ideology, which emerged in the Silicon Valley, refers to a mélange of hopeful technological determinism with rugged individualism, libertarian politics, cultural bohemianism, and neoliberal markets. With the convergence of information and communications technologies in the 1990s, the proponents of the Californian Ideology celebrated the democratizing potentialities of information technologies and sought to establish a new “Jeffersonian democracy” as well as a “global village” where all will be empowered to express themselves freely and to extend the frontiers of freedom inside and outside cyberspace. While the Californian Ideology advocates harnessed the integrative powers of the Internet and mobile technologies such as the iPhone, they have qualitatively changed how people, corporations, and governments negotiate “the boundaries of freedom.”

Steven Jobs was born in San Francisco in 1955 into a Syrian-German family. He was adopted at birth and grew up in Mountain View, California, in what is today known as Silicon Valley. Jobs’ biological father, Abdulfattah Jandali, was born into a Muslim family in Syria. Jobs was a pioneer of the personal computer of the 1970s, a champion of the Californian Ideology, and a leading advocate of the emancipatory potentialities and effects of information technology (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Steven Jobs fused information technology with capitalism and counterculture to create life changing technologies. Source: http://eandt.theiet.org/magazine/2014/01/new-utopias-for-old.cfm

Jobs was the co-founder of Apple Inc. and several other creative industries. With the “Think different” advertising campaign in 1997, he collaborated with industrial designer Jonathan Ive and developed a line of products that have fundamentally transformed how often people use technology and how people work, play, and connect with each other. These products include the iMac, the MacBook, the iPod, the iPhone, the iPad, iTunes, the iTunes Store, the App Store, and Apple Stores. Walter Isaacson, Jobs’ official biographer, described him as the “creative entrepreneur whose passion for perfection and ferocious drive revolutionized six industries: personal computers, animated movies, music, phones, tablet computing, and digital publishing.” (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. Bansky’s painting of Steven Jobs, “Son of a Migrant from Syria” at the “Jungle” Migrant and Refugee Camp, Calais, France, shows Jobs with a bag of his belongings and carrying a Mac Classic. Source: http://www.nbcnews.com/tech/tech-news/banksy-paints-son-migrant-syria-steve-jobs-refugee-camp-n478611

In conclusion, contrary to popular and simplistic portrayals of Arabs and Muslims as belonging outside American history and culture, the short accounts above of Estevan De Dorantes, Hadji Ali, and Steven Jobs indicate the embeddedness of Arabs and Muslims in the American experience. These pacesetters and risk-takers, each in his own way and in a creative composite of American and Arab-Muslim cultures, contributed to linking up dispersed places and regions across distance and to connecting people who inhabit diverse cultures and histories. Whether these acts of bringing people together take the form of trails and passageways of past centuries or the present-day information highways and circuits of the Internet, these trailblazers succeeded in pushing forward the frontiers of freedom and in extending the area of opportunity and possibility inside and outside the United States—making the American Dream and way of seeing and being in the world reachable to all. Arabs and Muslims have had and continue to have profound influences on making America great from sea-to-shining-sea. Would America be the same if these three individuals had been denied entry due to their religion, ethnicity, or country of origin? The contributions of these three Arab and Muslim individuals represent only three select examples. How many are there and how many more could be?

Hsain Ilahiane, Anthropology, University of Kentucky

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved