By Parag Khanna | (Informed Comment) | – –

While embedded with U.S. Special Operations Forces in 2007, I witnessed firsthand America’s incredible ability to apply technology to the battlefield. The digital map layered on Iraq’s topography was rich with satellite feeds, drone surveillance, heat maps of local violence, real-time situation reports from troops on the ground, and other forms of human and signals intelligence. With about two hours’ notice, special ops teams could strike anywhere in the country. During the so-called surge, the “op tempo” was relentless, and yet the coalition’s ability to hold Iraq together was fleeting at best. One cool and cloudy night, while walking around Balad Air Base northwest of Baghdad with a senior commander, I asked him point- blank, “Are all these gizmos necessary because you can’t speak Arabic?”

Political goals imposed on a complex cultural geography from halfway around the world stand little chance of surviving even a year. And the post-colonial map of the Middle East has lasted not even a century, and in many cases not even half that. Now it is time for the Arab world to build a new map for itself, to evolve from Sykes Picot towards a Pax Arabia.

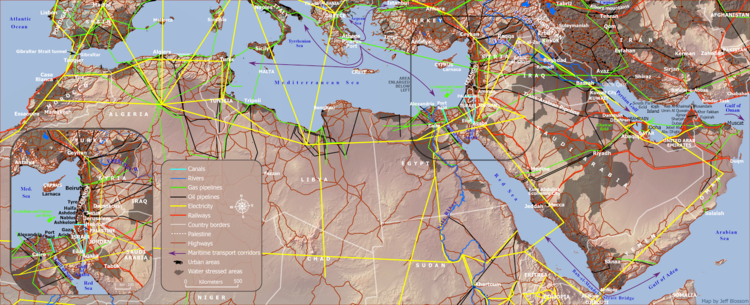

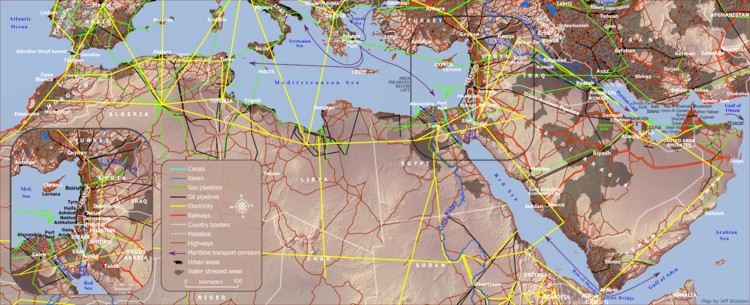

Credit: Jeff Blossom

The disintegration of major Arab states from Libya to Syria and Iraq is an invitation to rethink the principal lines that define the Middle East’s geography. With hundreds of thousands of casualties from the civil wars in Iraq and Syria, and neighboring states such as Lebanon and Jordan pulled into the vortex, the current Arab convulsions have been likened to Europe’s Thirty Years’ War. Arabs are now more concerned with their internal stability than external threats, and establishing their next map may take several decades. Indeed, Libya, Syria, and Iraq are still so chaotic that the future is hard to discern. But given the experience the Arab world already has with Islamic caliphates, foreign colonization, imperial suzerainty, insecure statehood, fitful pan-Arabism, tragic civil wars, and now widespread state collapse, it would be wise to learn from the past rather than repeat it.

The Arab world is ripe for reorganization. Rather than the futile pursuit of artificial national pillars under corrupt strongmen, the region must recover its historical cartography of internal connectivity. So dire is the decay of the region’s postcolonial system that even many Arabs-— not just Turks-— speak yearningly of the Ottoman Empire. A similar paradigm for the future would consciously build such fluid connectivity among urban oases to collectively enrich the region. Recall that it was Phoenician city-states such as Tyre in present-day Lebanon that sent forth merchants and explorers to settle colonies on Aegean and Mediterranean islands such as Sicily, in southern Spain, and at Carthage in North Africa. Indeed, from Tunis and Beirut to Damascus and Baghdad, some of history’s most successful trading centers have been Arab cities, a reminder that the Arab world is almost entirely urbanized. Its natural map is that of commercially oriented city centers with ties to the European, Turkic, and Persian realms—a legacy far richer than what the past century has produced.

ISIL demonstrated how borderless the Arab world is by rapidly conjoining Syria’s Deir al-Zor and Iraq’s Anbar provinces into a rump “Syriraq,” with further ambitions to capture all of the historically amorphous Al-Sham (Greater Syria). The map of ISIS-held areas looks not like a two-dimensional patch but like an octopus of tentacles extending along the “jihad highways” it controls extending outward from its strongholds in Anbar province. Intelligence Agencies’ real-time plotting of satellite feeds of oil trucks and financial data on black-market oil sales capture the shifting of ISIL’s supply lines. We cannot know today whether Anbar will remain an ISIL stronghold, return to Iraqi control, become an annex of Saudi Arabia’s Northern Borders province—or whether ISIL will succeed in partitioning Saudi Arabia as well.

The space in between the region’s civilizational anchors—- non-Arab Turkey and Iran, Arab powerhouses Saudi Arabia and Egypt-— is now up for grabs. Iraqi nationalism is meaningless, and Syria is an artificial failed state. Given its sectarian diversity and rugged topography, it is destined to devolve further, with Damascus and Aleppo remaining autonomous commercial hubs. The Middle East, it has long been argued, is but a collection of “tribes with flags.” Today tribes such as the Kurds that have no state have far more meaningful nationalism than Jordanians or Lebanese who do. Indeed, tribal states that hold their ground such as Kurdistan and Israel are the anchors of the region’s future map.

The Humpty Dumpty states of the Arab world will not be put back together again: The region is on course for more devolution, but aggregation is still far away. Getting from the current apocalypse to a higher stage of Arab self-organization will therefore be a marathon.

Arab nations’ geologic characteristics are more important than their political ones: They are either oil rich, oil poor, water rich, or water poor. With water scarcity threatening the very survival of countries like Yemen and Jordan, Arabs and their neighbors must build more water canals, pipelines, and railways rather than military checkpoints. For example, Israel, Jordan, and the Palestinians all favor a Red Sea–Dead Sea canal running along the Israel-Jordan border to provide potable water and irrigation. (A canal from the Mediterranean to the Dead Sea is also under study.)

In the 1940s, the Trans-Arabian Pipeline built by Standard Oil and Chevron was the world’s longest, stretching over twelve hundred kilometers from Abqaiq in eastern Saudi Arabia to Lebanon. Over the decades, it became a symbol of the Arab world’s own bickering and inability to cooperate as sovereign brothers, with Syria cut off over transit fee disagreements in the 1970s and Jordan in 1990 over its support for Iraq in the Gulf War. And yet today a new south-north pipeline from Saudi Arabia to a post-Assad Syria would be crucial to revive the northern Levant.

Turkey, meanwhile, could also become a far greater source of hydroelectric power and also infrastructure investment for Syria. Already Turkish construction companies have taken the lead in building up Kurdistan’s infrastructure and support Kurdish pipelines owing through Turkey to Ceyhan, from which oil is put on tankers and shipped to Europe as well as Israel’s port of Ashkelon despite Baghdad’s objections. Qatar, which on paper is the world’s richest country per capita, produces almost no food, while its three desalination plants provide only enough water reserves for a single day. As it buys up agricultural land across Jordan and Syria, it should also subsidize modern desalination plants and irrigation systems for them to boost food production. In all these ways, infrastructure connectivity creates the essential contiguity that political borders inhibit.

The space between the Mediterranean Sea and the Tigris River can still earn its place on the emerging Silk Roads between Europe and Asia. Arabs will need connectivity as a driver of long-term growth if for no other reason than that both the United States (already) and China (eventually) are diversifying away from Arab oil and gas supplies. They will have to become thriving urban hubs connecting and servicing all the continents on their periphery, including Africa. Westerners hesitate to draw any more maps (publicly, at least) for the region they so cravenly carved up last century, while the Arab regimes left standing are too busy manipulating local forces to put forth a collective long-term vision. But if Sykes-Picot has failed them and chaos is engulfing them, they must draw their own maps of Pax Arabia to have something to aspire to.

Parag Khanna is a CNN Global Contributor and the author of the new book CONNECTOGRAPHY: Mapping the Future of Global Civilization

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved