By Hsain Ilahiane | (Informed Comment) | – –

The Founding Fathers wrote the electoral college in the United States Constitution.

In late summer 2004, I became a naturalized United States citizen in Des Moines, Iowa. The following November election day, with my voting card in hand, sure-footed and full of excitement, I walked over to my precinct polling station, sited in one of the neighborhood’s churches, and performed my newly minted constitutional right to vote in the presidential elections. Upon the completion of my civic duty, the polling station monitors rewarded me with cookies and an I-Voted-sticker which I proudly placed over the left pocket of my fleece-lined flannel shirt for all to see. I still keep the I-Voted-sticker, now decorating my cassette and CD player and in prominent display in my living room. As a first-time voter, the I-Voted-sticker still reminds me not only of my initiation into the rituals of American politics but also of my encounter with participatory democracy. The sticker, and the relic that it has become and in a tangible way, still represents my transition from being a subject in a Third World and tribal context I left behind, a context saturated with technicalities of elections and little or no democracy, to being a citizen in a First World participatory democracy where I have gained agency and my vote counts, and for that matter, everyone’s vote counts and makes a difference in the outcome of who wins and who loses in the presidential elections.

Later on that night of November 2004 while watching the election results come in, television reporters, pundits, and commentators kept stressing the necessity of the magic number of 270 electors for George W. Bush to win the election. The magic number of 270 electors was also cloaked in a fast-paced discussion of the legal context behind the electoral college and the popular vote modalities, and keyed into this discussion, was the fact that the winner of the presidential election is not picked by the direct popular vote (one man, one woman, one vote) but appointed by the indirect electoral college– a political body made of 538 party leaders and members or electors. Today, of course, citizens vote directly for electors or representatives but the electors are not legally bound to vote for any particular candidate and could act as faithless electors if they choose to do so. It is worth remembering that the 2004 presidential elections came on the heels of a spirited election results contest between Al Gore and George W. Bush in 2000. Al Gore won the popular vote but lost the presidency. In 2016, Donald Trump lost the popular vote and won the presidency. Unlike 2000, where the election race results were tight, Hillary Clinton beat Donald Trump by

Despite the fact that I took a course on American Government in undergraduate school, the genealogy and historical context of the electoral college concept remained nebulous and its analytical prominence gained importance only in the presidential election season. As I was refreshing my encounter with the political and historical setup of the American election system and learning about the legal bricolage it took to stitch it together, I found myself going back and forth between the American legal scene that gave birth to the electoral college and my familiar Berber upbringing and ethnographic research I carried out in the multi-ethnic communities of southern Morocco. The more I learned about the founding era of the electoral college, the more I found myself engaged in a comparative exploration of the differences and similarities between Berber and American political institutions. I kept thinking that both systems, despite that one is federal and the other tribal, have actually more in common in terms of their political formation and complexity. While American institutions were constructed in historical settings shaped by slavery, the Berber structures were defined by social and ethnic stratification in southern Morocco. Both societies developed political structures in which they applied the notions and tools of racism and discrimination to deny direct political representation to non-white men and women. Is it then possible that the electoral college is essentially a tribal institution too? Could it be that the electoral college is the American version of the Berber jama`a?

With respect to the electoral college,

The compromise of the electoral college framework, which is written in the Constitution, has remained unchanged since the Civil War and despite the abolition of slavery that conferred citizenship and voting rights to black people. It also caused five candidates to lose the race to the White House after they won the popular vote — most recently in 2016, when Hillary Clinton lost to Donald Trump. While there are many criticisms of the value and utility of the electoral college in 21st century politics, one criticism that is seldom brought out into the light is its embeddedness in and connection with slavery and ways in which southern slave states used it to protect slavery and its oppressive racist infrastructure, remnants of which still inform and maintain the political architecture of large disenfranchised populations. To the point, the electoral college included a three-fifths clause, where black men and women were counted as three-fifths of a white person. This clause, some legal scholars argue, not only was used to give slave states more electoral votes but it also provided them with political power to establish a dominant white class. Additionally, it allowed states to enact discriminatory voting laws and regulations despite the 1965 Voting Rights Act that was passed to fight the compression and suppression of civil rights and other measures (Perea 2012; Finkelman 2002).

Today the electoral college, an institution which dates back to the late 18th and early 19th century, gives smaller and/or swing states with white majority voters a disproportionate power in deciding the outcome of presidential elections, pushing millions of voters to the sidelines. A recent statistical analysis of the electoral college results by Gelman and Kremp (2016) found that “The probability of one person’s vote being decisive… ranged from roughly one in a million for a resident of New Hampshire — a swing state with a relatively small population — to less than one in one billion in states that are reliably “red” or “blue,” such as New York, California, Kansas, and Oklahoma… and particularly within swing states, the Electoral College amplifies the power of white voters by a substantial amount.”

This is remarkable for three critical reasons. The first reason deals with the obvious principle of fair and direct representation (one man, one woman, one vote) which is connected with the urgent need to answer the questions that are on almost everyone’s mind: why vote at all if one’s constitutional right to vote is put aside by overrepresented white voters in battleground states? How is it that 2.8 million more people voted democratic in 2016 yet political power stayed in Republican control? Could it be that the wider issues of gerrymandering and injections of big money into politics are exacerbating the undemocratic leftovers of the electoral college? The second reason is the incoherence and contradiction that are part and parcel of claims made of and for democracy in Western democratic societies. The social drama of elections and their constitutive elements (political parties, campaigns, super political action committees, conventions, and nominations) are put together to authenticate and intensify the democratic narrative, feeling, and practice at the same time they are made to throw in barriers against full and meaningful political participation of their subjects and/or citizens. Simply, the contradictions in the claims of the electoral college allowed the dominant political class not only to define who is a subject, who is a citizen, but also the modalities that subjects have to go through on their path to be counted and transformed into citizens. The third reason this is remarkable is that the electoral college, a relic of slavery and racism of the founding era, bears family resemblance to the Berber tribal institution of jama`a.

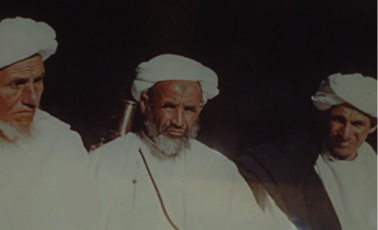

Berber notables and electors, southern Morocco, circa 1933.

The Arabic term jama`a refers to the assembly of notables of a tribe, or a tribal section, which in Berber society, acts as a legislative, executive, and judicial entity. In some places it goes by the name of taqbilt, the term being the Tamazight (Berber) form of the Arabic word, qabila: tribe and/or confederation referring to a political unit based usually on a segmentary lineage framework. It applies the abrid or qanun which are embodied in the corpus of customary law, called azerf. This legal coded is oral as well as written. A select group of elders who retain the legal code in memory are known as aït al-haqq (men of truth), and serve as final arbiters in determining the rules of the code. The practice of community consensus through jama`a indicates that Berber society is relatively democratic, though only elder men generally participated. Women, young men, slave-descendants, and Haratine (black people) were excluded until the recent past.

Customary laws, called azerf and ta`qqit in Berber, are documented in local legal treatises. Some of these legal documentsdate back to the late 18th and early 19th century, and deal with the ethno-political life of communities, management of the palm grove and irrigation, law and order, and sharecropping arrangements. These documents still inform much of the power relationships among ethnic groups in most present day communities and illustrate how discrimination and religious ideology were put to work in a stratified society with white Berbers and holy Arabs on top and Haratine and slave-descendants at the bottom and denied access to land ownership and political participation in the tribal council.

The internal and political affairs of Berber communities were (some are still) administered by the local agnatic lineage based council called taqbilt or jama`a. The jama`a was composed of id-bab n-imuran or lineage representatives headed by amghar n-tamazirt, the country or land chief. The amghar was elected every year from a different lineage. The id-bab n-imuren, meaning the people who own land and shares of protection of the non-Berber groups, were nominated to the council by the amghar but not appointed by the members of their own lineages. For instance, in old town village, one Berber sub-tribe was divided into six lineages and these six lineages make the taqbilt or jama`a of the community. Each year, after the wheat harvest, they gathered to elect the annual amghar or chief of the community. The office of the chief rotated among the lineages. Once all the lineage representatives, as well as a the fqih (imam)of the local mosque to bless the gathering with benediction, were assembled in the jama`a meeting room, the elections started. The candidates from the incoming lineage sat on a red carpet and waited while the electors from the other lineages went outside to discuss their choice of the individual to be elected. Once the electors made their decisions, they came back, walked in a circle around the candidates, reported their decision to the fqih, and finally the fqih put his finger on the head of the person who was about to assume leadership.

The annual elections of the amghar n-usgguas (annual leader) by the lineage constituency is what Gellner (1969) calls “rotation and complementarity.” This process safeguarded the political system, Gellner argues, in two critical ways: the electors could never elect themselves and its annual rotation acted as a check against any abuse of power and corruption. Neither candidates for the office of the chief nor the members of their lineages had the right to vote. Thus, through this process of complementarity, delegation of authority and representation, and exclusion of women and non-white populations such as slave-descendants and Haratine, the political system paradoxically remained immune to any temptations of hegemony of one group over another. However, post-colonial reforms coupled with the social mobility of the Haratine and former-slave descendants have to a large extent undermined the traditional workings of the jama`a. The social mobility of these former low-status groups was made possible by migration financial flows which allowed them to purchase land, which in turn, gave them the opportunity to have a voice and a place in the tribal council. While a few communities have grudgingly adjusted to these social and ethnic changes, most communities still resist the incorporation of Haratine and other former-slave descendants into decision making institutions.

In light of this brief comparative account, the institutions of the electoral college and the Berber jama`a appear to be cut from the same cloth and constitute remnants of a disquieting ethno-political era shaped by slavery, racism, and ethnic stratification. Both the electoral college and the jama`a privilege the idea and act of voting via the agency of delegation, and in the process, they both negate, or at best, short change direct participatory democracy. They devalue modern and progressive principles of fairness, equality, and dignity, and rob people of their capacity to make their history as they please. Both institutions are outdated and are out of step with peoples’ aspirations, and dare I say tribal. The question now facing us, anthropologists, is what is it that we must do to banish these tribal institutions from the vocabulary and practices of 21st century politics?

[1] I would like to thank Thomas Park (University of Arizona) and George Baca (Dong-A University, South Korea) for their valuable comments.

Hsain Ilahiane teaches at the University of Kentucky

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved