By Simon Mabon | (The Conversation) | – –

With a simple 67-word letter sent on November 2, 1917, the British foreign secretary, Lord Arthur Balfour, irrevocably changed the political and geographic landscape of the Middle East. Outlining British support for the establishment of a Jewish state, it set in motion a series of events that culminated in the declaration of the State of Israel in 1948 in what had previously been Palestinian land – and by extension, the eventual occupation of the West Bank and Gaza strip.

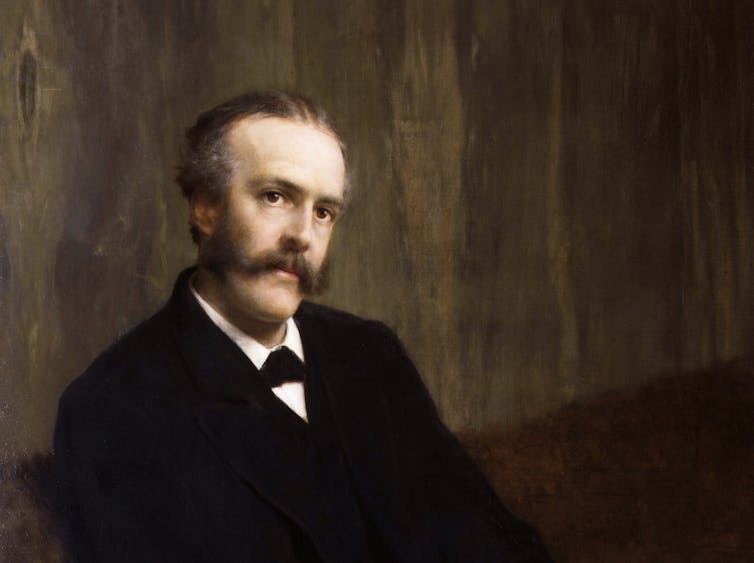

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema via Wikimedia Commons

Balfour’s letter was sent in a climate of secret diplomatic wrangling between British, French and Arab leaders over how best to divide Ottoman territory after World War I. The McMahon-Hussein Agreement of 1915, which promised independence to Arabs, was followed by the Sykes-Picot Agreement, which divided the Middle East into British and French zones a year later. Colonialism was at its apex, and the Balfour Declaration showed the zeal with which the British elite sought to influence and dominate people and territory the world over.

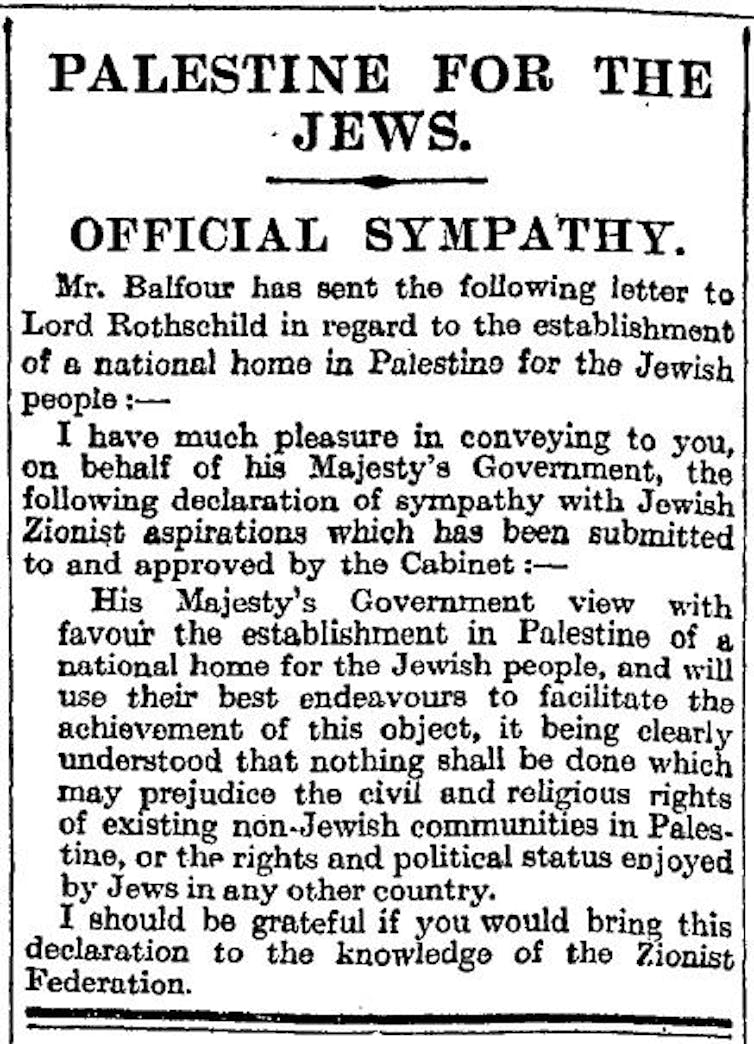

The letter from Balfour to Lord Walter Rothschild, a leading member of the British Jewish community, read as follows:

His Majesty’s government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.

Ultimately, the declaration promised a state to the Jews despite Palestinian natives comprising some 90% of the population. In the words of Palestinian scholar Edward Said, this was a declaration “made by a European power … about a non-European territory … in a flat disregard of both the presence and wishes of the native majority resident in that territory”. Its ramifications are still felt today.

Demolition and displacement

In 1948, an estimated 750,000 native Palestinians were forced from their homes in what is now known as the Nakba, or the catastrophe. The methods Israeli forces such as the Irgun used to drive them out had their roots in the British counter-insurgency methods that had been used against the Irgun themselves in the previous decade.

Moreover, prominent leaders of the burgeoning Israeli state, among them Moshe Dayan and Yigal Allon, had been trained by the British during previous collusion against the 1936 Arab revolt, where they ran special squads to regulate life in the mandate, with the support of the British.

Jewish migration to the mandate – regulated by the British – was increasing, rising from 9% to 27% of the local population between 1922 and 1935. And while space was not an issue, the transformation of urban areas was a key part of the British counter-insurgency operation.

Under the guise of urban regeneration, the British made 6,000 of Jaffa’s Palestinians homeless, with military personnel directing the demolitions. Similar practices are employed by the Israeli defence forces today in the West Bank, notably in Jenin and Nablus.

Wikimedia Commons

One of the new Israeli state’s main tools to facilitate urban change was the demolition of houses. Immediately after it seized the Old City of Jerusalem from Jordan in 1967, the government erased the city’s Maghriba Quarter, found in front of the Western Wall. In an attempt to facilitate cohesion between the newly seized territories and the rest of Israel, planning committees referred to British legislation that required the use of Jerusalem stone on all buildings. This urban transformation is a key part of political life in Jerusalem today where Stars of David are used to signify Israeli ownership; similar strategies are also found across the West Bank as settlers lay claim to land.

Although the declaration stressed that civil and religious rights should not be prejudiced, it was clear that the British were complicit in the development of infrastructure that was key to the formation of the Israeli state. Such developments may not have been always by design; after all, the British experienced a brutal terrorist campaign at the hands of Zionist extremist groups such as the Irgun and the Stern Gang.

Then and now

In the aftermath of the Nakba, Israeli leaders set about building a new state for Jews, transforming Palestinian land and urban environments into something that would unite the Jews already in Palestine and create a shared national identity. A key part of this state-building project was the establishment of planning committees to oversee the transformation of Tel Aviv and Jaffa. To this day, Tel Aviv’s streets bear names such as King George, Allenby and Balfour. Reflecting colonial dominance, signs were often topped with the streets’ English names rather than Hebrew ones.

In the early years of statehood, amid unrest in East Jerusalem and in the West Bank and Gaza, the Israeli state deployed a range of strategies to keep control. Homes were demolished, everyday life regulated through security measures, and a security barrier was built to separate Israel from the West Bank. From the off, these moves were justified through recourse to British Emergency Laws. First implemented in 1945 to prevent further violence by the Stern Gang and the Irgun, they still are routinely used to justify violence against Palestinians.

In 2010, after demonstating against the demolition of Palestinian homes, Adnan Geith was banished from his home through use of the Defence (Emergency) Regulations from 1945. The use of emergency powers goes much further; it played a central role in the occupation of Palestinian lands, resulting in the establishment of the regime that today helps Israel assert sovereignty over Palestine and control daily life.

The Balfour Declaration may be a century old, but its effects are as firmly entrenched as ever. In the corridors of Whitehall, Britain’s colonial legacy is a ghost – but for Palestinians, it remains a fact of life.

Simon Mabon, Lecturer in International Relations, Lancaster University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved