By Linda Kiernan | (The Conversation) | – –

The power of laughter is something of a theme in Donald Trump’s presidency. Trump’s humourless response to Barack Obama’s jibes at the White House correspondents’ dinner in 2011 allegedly steeled his reserve to run for president in the first place; the New York Times recently asked why Trump himself seemingly never laughs at all.

And in October, it was reported that a US woman would stand a second trial for simply laughing at Trump’s attorney general, Jeff Sessions, at a congressional hearing. Desiree Fairooz had already been tried for this “contempt” – or as Stephen Colbert termed it, “first-degree chuckling with intent to titter”.

The prosecuting attorney stated that Fairooz “wasn’t just merely responding, she was voicing an opinion”. The argument that laughter alone was enough to convict was thrown out by the first judge; Ms Fairooz’s “brief reflexive burst of noise” has just been dismissed by the Department of Justice.

In the US’s rough political climate, laughter is having a hard time, too. Many questions on its worth have been posed: is laughter muffling potentially more effective forms of criticism? Is satire defusing political commentary by humanising its targets? Alec Baldwin has expressed concern that his impression of Trump on Saturday Night Live has disarmed real incisive commentary, reducing the presidency and its incumbent to a crass approximation of the more troublesome reality.

Weapons of the weak

What these qualms reflect is that as a political gesture, laughter has a considerable range. It can be used to defuse a situation, or to inflame. It can serve as a conciliatory gesture, and equally as a means of defiance. It can single out a target while also uniting a crowd. Laughter is used by many politicians; when they laugh along they can diffuse tension, and relax the public gaze. They become relatable, approachable, and at least acknowledge that they are meant to be the their audience’s equal, not their better.

But laughter can also carry a potentially revolutionary force. It’s a way for a group to recognise their common view of a figure, an issue, or a political standpoint. To quote George Orwell: “Every joke is a tiny revolution.”

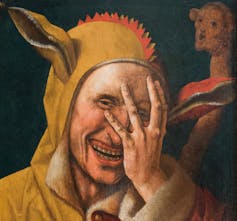

Wikimedia Commons

Laughter was for much of history considered the mark of a fool, an uncontrolled reaction of the body and mind that betrayed an absence of reason. Many, including Plato and Hobbes, viewed laughter as a base expression, an animalistic response, devoid of reason. But in the 20th century, many scholars, including Henri Bergson and Mikhail Bakhtin, came up with more nuanced analyses of laughter and its political clout.

It was true that in what Bakhtin called carnivalesque culture, laughter became synonymous with the grotesque and the obscene, but it still serves an important social purpose: a means for those who had no other recourse to protest to register their views of the status quo.

Rumour, gossip, and laughter have been termed weapons of the weak, opportunities to defy authority in unofficial and often indefinable ways. Traditionally, this has made them harder for oppressive regimes to clearly identify and possibly prosecute. To this day, laughter remains a means of political expression for those who are otherwise disenfranchised: it subjects the powerful to both ridicule and scrutiny.

Get it?

In the early modern period, laughter played a significant role as a political language. The celebrations of the Feast of Fools and the Feast of the Ass allowed people of all levels of society to both display their places in the social order and to ridicule them. It was at once an assertion of authority and a challenge to it.

During the 18th century, political satire gained much ground. Enlightenment authors across Europe took aim at institutions of authority, often in underhand and opaque ways to circumvent censorship. Oftentimes “getting the joke” affirmed one’s membership of a political creed or club. Indeed, when political upheaval took hold in France, the need to laugh “appropriately” emerged as a measure of one’s loyalty to the revolution. The “rire sardonique”, the aristocratic snigger, was replaced with the good-natured belly-laugh of the “sansculotte” – the honest, genuine expression of mirth of the ordinary man, rather than the contrived, artificial ridicule of the polished courtier.

This idea of laughing the right laugh, of laughter as an indication of identity and mentality, is echoed in Sergei Eisenstein’s 1935 essay, Bolsheviks Do Laugh. The laughter of the Bolshevik, Eisenstein wrote, was loaded with the weight of revolution, of striving for the proletarian order. Unlike the laughter of others, Bolshevik laughter was not idle, nor frivolous. It was invested with the irony of Chekhov, the bitterness of Gogol; it was not for mere amusement, it had a higher purpose. For Eisenstein, laughter represented ways of seeing and understanding the world.

Politicians and those in positions of authority who actively resist or deny the right of those who have elected them to deride, ridicule, and laugh at them are also denying the idea that they are their citizens’ equal, that they are subject to scrutiny and indeed that they are accountable. While standards of comedy and perceptions of laughter have changed over time, one thing has remained immutable: laughter has always provided a means of dialogue between those in power and those they rule.

![]() When that dialogue is suspended – or rather, when the powerful lose their sense of humour – it’s time to worry.

When that dialogue is suspended – or rather, when the powerful lose their sense of humour – it’s time to worry.

Linda Kiernan, Lecturer in French History, Trinity College Dublin

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

—–

Related video added by Juan Cole:

Paul Manafort’s House Cold Open – SNL

© 2026 All Rights Reserved

© 2026 All Rights Reserved