Joseph McQuade | (The Conversation) | – –

Recently an academic article, asserting the historical benefits of colonialism, created an outcry and a petition with over 10, 000 signatures calling for its removal.

The Case for Colonialism, published in Third World Quarterly by Bruce Gilley, argues Western colonialism was both “objectively beneficial and subjectively legitimate” in most places where it existed.

CC BY

Gilley, an associate professor of political science at Portland State University, claims the solution to poverty and economic underdevelopment in parts of the Global South is to reclaim “colonial modes of governance; by recolonizing some areas; and by creating new Western colonies from scratch.”

Understandably, the article faces widespread criticism for whitewashing a horrific history of human rights abuses. Current Affairs compared Gilley’s distortion of history to Holocaust denial.

Last week, after many on the journal’s editorial board resigned, the author issued a public apology for the “pain and anger” his article may have caused.

(Shutterstock)

Whether the article is ultimately retracted or not, its wide circulation necessitates that its claims be held up to careful historical scrutiny. As well, in light of current public debates on censorship and free speech versus hate speech, this is a discussion well worth having. Although this debate may seem as though it is merely academic, nothing could be further from the truth.

Although it may seem colonialist views are far behind us, a 2014 YouGov poll revealed 59 per cent of British people view the British Empire as “something to be proud of.” Those proud of their colonial history outnumber critics of the Empire three to one. Similarly, 49 per cent believe the Empire benefited its former colonies.

Such views, often tied to nostalgia for old imperial glory, can help shape the foreign and domestic policies of Western countries.

Gilley has helped to justify these views by getting his opinions published in a peer review journal. In his article, Gilley attempts to provide evidence which proves colonialism was objectively beneficial to the colonized. He says historians are simply too politically correct to admit colonialism’s benefits.

In fact, the opposite is true. In the overwhelming majority of cases, empirical research clearly provides the facts to prove colonialism inflicted grave political, psychological and economic harms on the colonized.

It takes a highly selective misreading of the evidence to claim that colonialism was anything other than a humanitarian disaster for most of the colonized. The publication of Gilley’s article — despite the evidence of facts — calls into question the peer review process and academic standards of The Third World Quarterly.

Colonialism in India

As the largest colony of the world’s largest imperial power, India is often cited by apologists for the British Empire as an example of “successful” colonialism. Actually, India provides a much more convincing case study for rebutting Gilley’s argument.

With a population of over 1.3 billion and an economy predicted to become the world’s third-largest by 2030, India is a modern day powerhouse. While many attribute this to British colonial rule, a look at the facts says otherwise.

From 1757 to 1947, the entire period of British rule, there was no increase in per capita income within the Indian subcontinent. This is a striking fact, given that, historically speaking, the Indian subcontinent was traditionally one of the wealthiest parts of the world.

As proven by the macroeconomic studies of experts such as K.N. Chaudhuri, India and China were central to an expansive world economy long before the first European traders managed to circumnavigate the African cape.

During the heyday of British rule, or the British Raj, from 1872 to 1921, Indian life expectancy dropped by a stunning 20 per cent. By contrast, during the 70 years since independence, Indian life expectancy has increased by approximately 66 per cent, or 27 years. A comparable increase of 65 per cent can also be observed in Pakistan, which was once part of British India.

Although many cite India’s extensive rail network as a positive legacy of British colonialism, it is important to note the railroad was built with the express purpose of transporting colonial troops inland to quell revolt. And to transport food out of productive regions for export, even in times of famine.

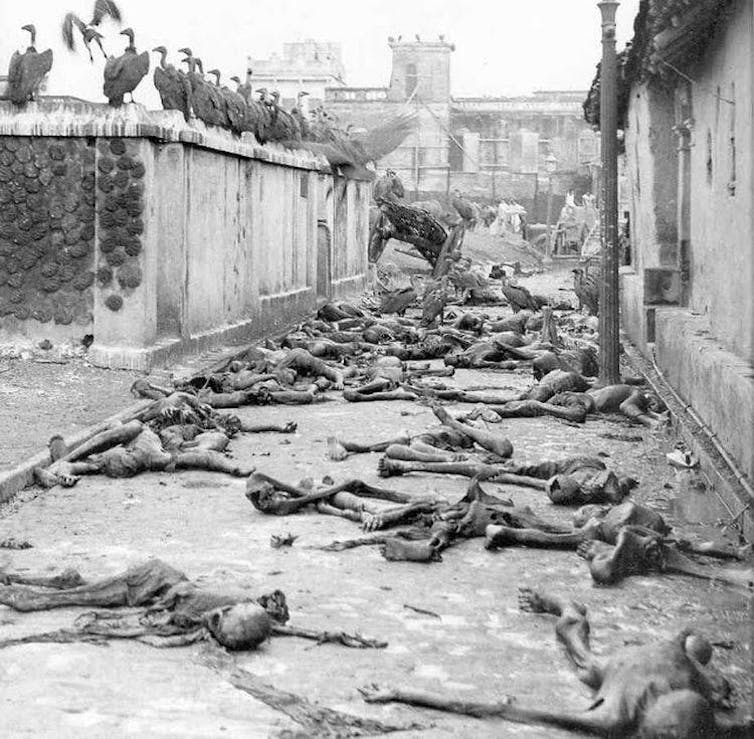

This explains the fact that during the devastating famines of 1876-1879 and 1896-1902 in which 12 to 30 million Indians starved to death, mortality rates were highest in areas serviced by British rail lines.

(Shutterstock), CC BY

Colonialism did not benefit the colonized

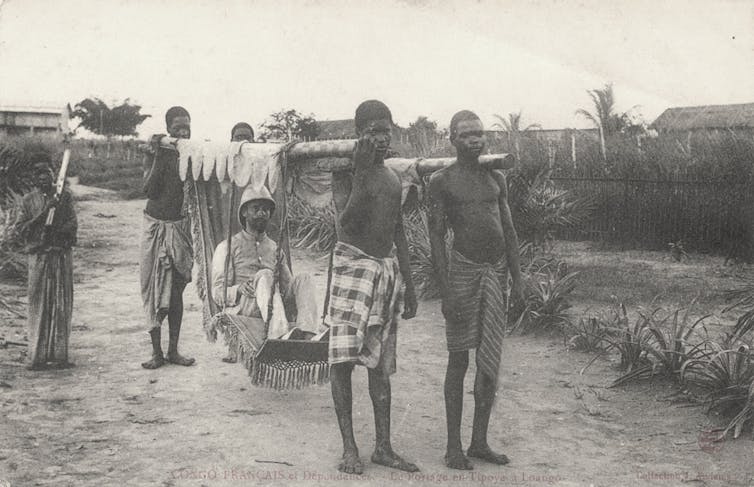

India’s experience is highly relevant for assessing the impact of colonialism, but it does not stand alone as the only example to refute Gilley’s assertions. Gilley argues current poverty and instability within the Democratic Republic of the Congo proves the Congolese were better off under Belgian rule. The evidence says otherwise.

Since independence in 1960, life expectancy in the Congo has climbed steadily, from around 41 years on the eve of independence to 59 in 2015. This figure remains low compared to most other countries in the world. Nonetheless, it is high compared to what it was under Belgian rule.

Under colonial rule, the Congolese population declined by estimates ranging from three million to 13 million between 1885 and 1908 due to widespread disease, a coercive labour regime and endemic brutality.

Gilley argues the benefits of colonialism can be observed by comparing former colonies to countries with no significant colonial history. Yet his examples of the latter erroneously include Haiti (a French colony from 1697 to 1804), Libya (a direct colony of the Ottoman Empire from 1835 and of Italy from 1911), and Guatemala (occupied by Spain from 1524 to 1821).

By contrast, he neglects to mention Japan, a country that legitimately was never colonized and now boasts the third largest GDP on the planet, as well as Turkey, which up until recently was widely viewed as the most successful secular country in the Muslim world.

These counter-examples disprove Gilley’s central thesis that non-Western countries are by definition incapable of reaching modernity without Western “guidance.”

In short, the facts are in, but they do not paint the picture that Gilley and other imperial apologists would like to claim. Colonialism left deep scars on the Global South and for those genuinely interested in the welfare of non-Western countries, the first step is acknowledging this.

Joseph McQuade, SSHRC Postdoctoral Fellow, Centre for South Asian Studies, Munk School of Global Affairs, University of Toronto

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Editor’s Note: The Conversation Canada is revealing its most viewed stories of 2017. This article is No. 4 on our list.

——-

Related video added by Juan Cole:

Al Jazeera English from 2011: “Kenyans allowed to sue UK for colonial abuse”

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved