By Moujan Mirdamadi | (The Conversation) | – –

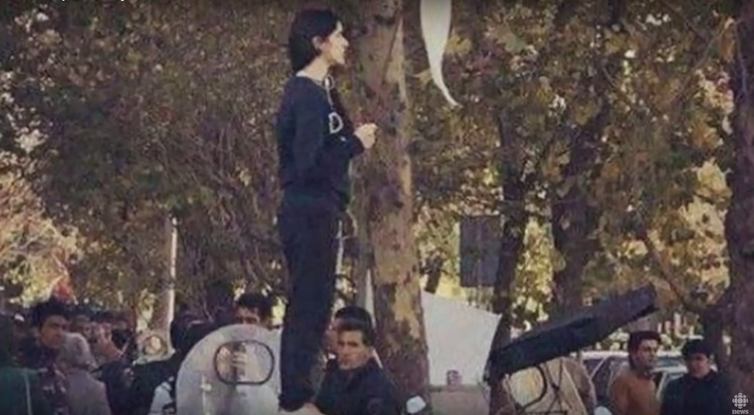

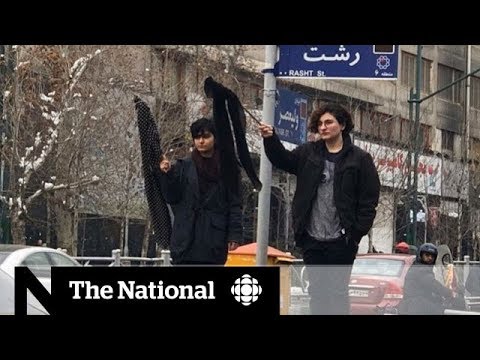

Protests against Iran’s mandatory hijab law – which requires all women to wear it in public – have sprung up across Iran in the first few weeks of 2018. Women, acting individually, stood on utility boxes in public places, taking off their headscarves and holding them up as flags. Some men also took part in the protests.

The National via YouTube

The government’s reaction so far has been to arrest 29 people connected to the campaign against the hijab.

But a newly released report by the Iranian government shows that 49% of the population are against the country’s compulsory hijab law, although the real number is likely to be higher.

The hijab has an important place in the power dynamic between society and the ruling Iranian regime. During the revolution in 1978-79, led by Ayatollah Khomeini, the hijab became a symbol of resistance and protest against the monarchy of Mohammad Reza Shah. The Pahlavi regime of the Shah and his predecessor had attempted to modernise the country, but its policies clashed with the religious values of a large part of the population.

Publicly wearing a hijab became a symbol of protest and solidarity against the monarchy, regardless of how religious a woman was. But wearing a veil was not compulsory for protesters, neither was making it so a demand driving the revolution.

Within a few years of the revolution, the Iran-Iraq war was used as an excuse to clamp down on domestic opposition forces and to introduce strict domestic laws. In 1985, it became mandatory for women to wear the hijab with a law that forced all women in Iran, regardless of their religious beliefs, to dress in accordance with Islamic teachings. The hijab became a tool for implementing the government’s strict religious ideology.

A symbol of oppression

The new law marked an ideological way of governing that continues today. The compulsory hijab law has been used to exclude women from various areas of public life, either by explicitly banning women from certain public spaces such as some sports stadiums, or by adding restrictions on their education and workplace etiquette. More generally, it is also used to exclude anyone who disagrees with the ideology of the regime, who are branded as having “bad-hijab”. Not adhering to hijab continues to be seen as a hallmark of opposition to the government.

The law is also used to justify the regime’s increasing involvement in citizens’ private lives. From an early age, girls are forced to wear headscarves in school and public places. Teenagers and young people in Iran are routinely stopped by the “morality police” responsible primarily for policing people’s appearances and adherence to wearing the hijab.

For women it is the way they wear their headscarves and the length of their overcoats. Men are prohibited from wearing shorts, having certain haircuts that could be seen as Western, and wearing tops with “Western” patterns or writings.

In recent years, it has become common practice for the police to raid private parties, arresting both girls and boys on the basis of not adhering to the hijab law. Punishments range from fines to two months in jail.

Going public

Such violations of citizens’ private lives add to a lack of happiness, satisfaction, and hope in Iranian society. This is something the government has acknowledged as one of the many social crises facing the nation.

The protests against the hijab followed widespread demonstrations in late 2017 that shook over 80 cities in Iran. Many of the social analyses of these recent protests, which were in large part fuelled by economic hardships, point to a strong mood of hopelessness.

The compulsory hijab law contributes to this mood, which is pushing opposition to the regime into the private sphere of people’s lives. It is this hidden opposition that fuels the scattered, yet strong public displays of unrest in Iran against the oppressive forces of the regime.

As the anniversary of the 1979 revolution approaches on February 11, some women are boldly bringing these protests back into the public arena. By protesting against the mandatory hijab law, Iranians are protesting against the very ideology of the regime.

The hijab has once again become a symbol, this time of the ideology and power of a regime over its people. By protesting this notion, Iranians are drawing a boundary for the government: individuals have the right to their body and their appearance and this is not a matter for the governing regime to enforce.

What Iranian society is most in need of is hope – not only as a driving force for active participation of citizens, but also as a unifying force bringing together different factions of the society. The protest against the hijab is symbolic. But it is also a protest with a clear demand, and with the potential to bring together Iranians, regardless of gender or religious beliefs. It could be just what Iranian society needs to restore hope for the future, and more importantly, for change.

Moujan Mirdamadi, PhD Candidate, Lancaster University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved