By Pamela Abbott & Andrea Teti | (The Conversation) | – –

Egyptians are voting in presidential elections on March 26-28. Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, who grabbed power in 2013, is set to win another term by a landslide. Yet this is far from a sign of strength: opposition candidates have been silenced, and even pro-government media are being purged of the slightest undertone of dissent.

Al-Sisi’s grip on power may appear firm, but his country’s problems can’t be thrown into jail like his opponents. His predecessors Hosni Mubarak and Anwar Sadat learned this the hard way.

Yet don’t expect much hand-wringing from the West about Egypt’s stability in the coming days – despite its having been through a revolution and a coup already this decade. Governments and other strategists only appear to worry about countries in this region once discontent turns “hot” – like in Syria, Yemen, Libya or Iraq.

Our research shows that this may be a serious and costly mistake. The whole region is suffering from exactly the same deep-seated problems as before the Arab Spring of 2010-11. In Egypt and various other apparently stable countries, there are very high levels of discontent that could easily boil over.

Then and now

The uprisings earlier in the decade were not simply demands for Western-style democracy. Protesters may have been disillusioned by all the election rhetoric from these authoritarian regimes in democratic clothing, but they were primarily disgusted by corruption, abuse of power and economic inequality. They wanted governments that would address these concerns rather than lining their own pockets and those of their cronies.

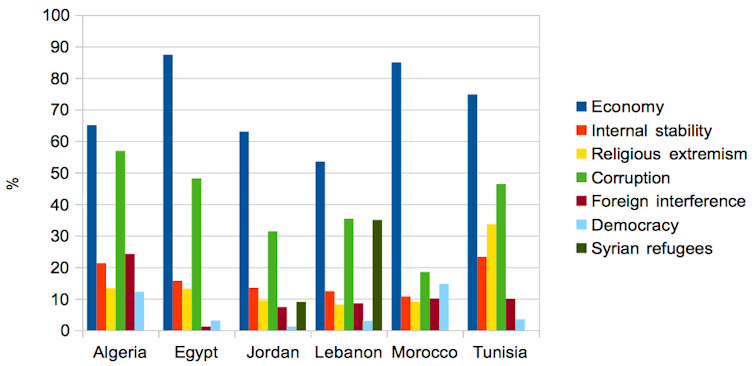

Unfortunately little has changed, as newly released opinion polls show for Morocco, Algeria, Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon and Tunisia – with upwards of 1,000 people surveyed in each country. While citizens worry about issues their governments prioritise, such as security, terrorism and religious extremism, their main concerns are the same as in 2010 – decent jobs, inflation, inequality and corruption.

Top two challenges by country

Arab Barometer, 2016.

People don’t believe their governments are responsive to their priorities. Fewer than one third of Egyptians think so, while in Morocco, Tunisia, Algeria and Jordan that figure drops to a quarter or less. In Lebanon it is a mere 7%.

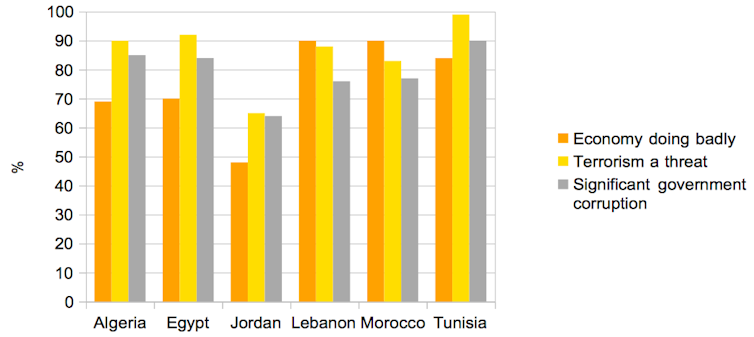

Across all six countries an astonishing 85% or more think their governments are not making a serious effort to tackle corruption. Meanwhile, 75% or more are not satisfied with their governments’ efforts to create jobs or fight inflation.

Views on economy, corruption and terrorism

Arab Barometer, 2016.

The discontent is worst in Lebanon, where fewer than 5% of people approve of the government’s work. Even the performance on internal security – the one area where citizens in the other five countries are relatively satisfied – was considered adequate by only a quarter of Lebanese respondents.

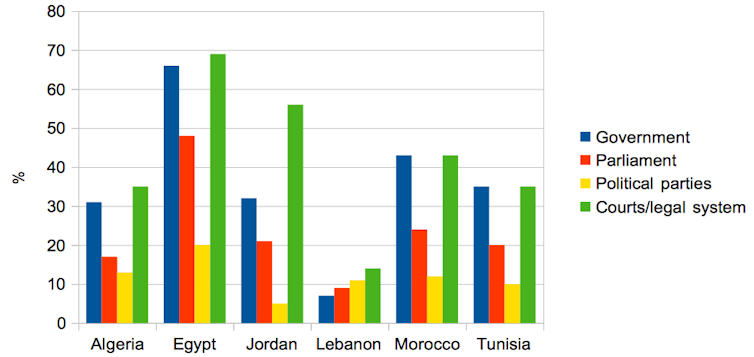

This region-wide disenchantment translates into low confidence in parliaments and political parties, the key institutions which ought to be representing citizens’ interests. Confidence varies from country to country: Lebanon again scores poorly. Egypt fares better than others, but this owes more to intense government propaganda than any real effectiveness.

Trust in state institutions

Arab Barometer, 2016.

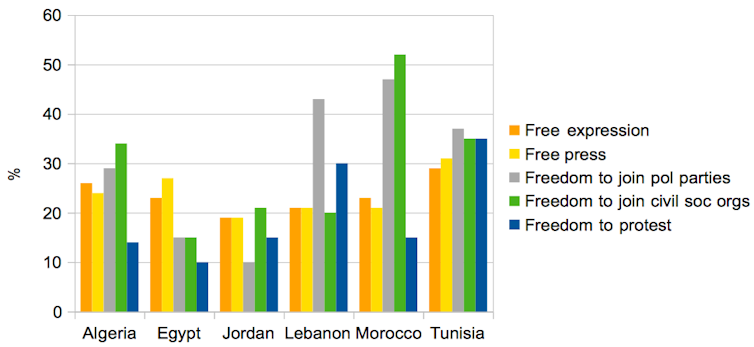

Citizens also don’t feel they have the civil and political rights necessary to legitimately express their grievances and push their governments for reforms. When people are unable to adequately express their unhappiness, it inevitably increases the potential for radicalisation.

Views on civil rights

Arab Barometer, 2016.

Little changed

As a result of the Arab uprisings, governments fell in Tunisia, Egypt, Yemen and eventually Libya, while there were more limited political changes in Jordan and Kuwait. Governments in other countries announced political concessions, including Morocco, Algeria, Oman and Saudi Arabia.

Yet since the issues which drove many of these protesters to the streets have not been addressed, their governments remain vulnerable both to mass mobilisation and to less obvious forms of radicalisation – as recent protests in Tunisia show.

Western policymakers and academics concerned with security are at risk of missing this. They do not seem to have learned the lessons of the Arab uprisings. Absent armed conflict, they still tend to dismiss the importance to stability of social cohesion, inequality and poor political representation.

Wikimedia

We must therefore reassess the stability of countries like Egypt. We must stop assuming their leaders will forever be able to simply repress dissent, and stop assuming that such repression doesn’t come with costs and risks, both human and political.

These countries are in fact security “sinkholes”: regimes whose foundations erode while apparently seeming stable, often to the point of collapse. Far from being a sign of strength or stability, remaining deaf to the needs of the people make things worse in the long run.

![]() As al-Sisi makes his inevitable victory speech, we would be wise not to ignore these warning signs. Until we learn that conflict must be dealt with at its roots, history is liable to just keep repeating itself.

As al-Sisi makes his inevitable victory speech, we would be wise not to ignore these warning signs. Until we learn that conflict must be dealt with at its roots, history is liable to just keep repeating itself.

Pamela Abbott, Director of the Centre for Global Development and Professor in the School of Education, University of Aberdeen and Andrea Teti, Senior Lecturer in International Relations, University of Aberdeen

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

—-

Bonus video added by Informed Comment:

AFP: “Egypt heads to polls to choose between Sisi and ‘rival'”

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved