College Park, Md. (Qantara.de) – Some are suggesting that Muslims are bringing anti-Semitism to Europe. However, it was in fact Europeans who took anti-Semitism to the Arab world in the first place. Diplomats in particular played an contemptible role.

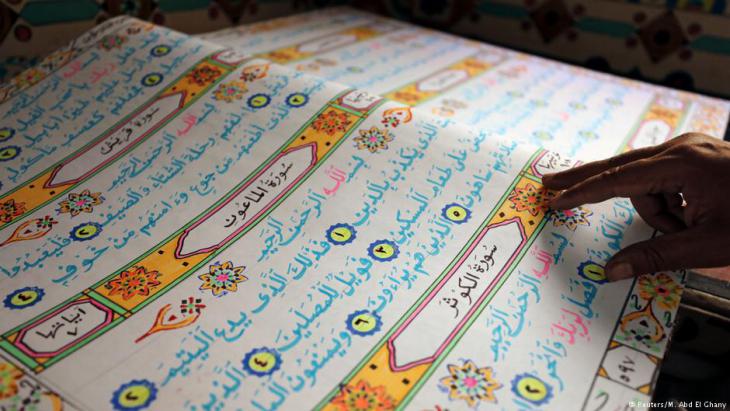

Holy books are what people make of them: after all, even the word of God needs to be understood and interpreted. The same applies to anti-Jewish statements in the Koran. Today, it isn’t just so-called critics of Islam who describe them as anti-Semitic; Muslim hate-preachers too like to quote them. In the field of traditional Koranic exegesis, this is a new kind of misuse.

For over a thousand years, Muslims have worked hard to make their word of God applicable as a moral and legal doctrine. Scholars claimed the exclusive right to interpret it. While this process wasn’t democratic, it guaranteed that extreme, isolated interpretations stood little chance.

Verses calling for violence against Jews, for example, are embedded in reports about historical events. When the Prophet emigrated from Mecca to Medina in 622, he formed an alliance with the local population, which included some Jewish tribes. It is said that when these tribes broke the contract, Mohammed and his followers took revenge. Hatred of Jews in the early Islamic tradition sprang from the precarious position of the Muslim community, which was in competition with social adversaries. When seen this way, it was clearly associated with a specific situation.

Islamic scholars have always seen it more or less like this. Over the centuries, Jewish life, culture, economy and scholarship thrived under Islamic rule. Historians are agreed that Jews had a much better life under Islam than under European Christianity. While there was, of course, violence against people of other faiths in the Islamic world too, Islamic scholars had more problems with Christians and the doctrine of the Holy Trinity, which to them smacked of polytheism.

No anti-Semitism founded on race or religion

The current debate in Germany about anti-Semitism among Muslim migrants must be viewed against this historical backdrop. There is no tradition of anti-Semitism in Islam founded either on race or religion. And yet these days, it is widespread in majority-Muslim countries.

Neither racism nor the violence that results from it can be justified. However, the acceptance of anti-Semitic prejudices among Muslims should be attributed to political and social rather than religious factors. Without the colonial subjugation of the Arab world in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the spread of anti-Semitic thought, both there and in other Islamic countries, is almost unthinkable.

The first truly anti-Semitic incident in the Middle East occurred in Damascus in 1840 among Catholic missionaries. An Italian-born monk had disappeared, and several statements extracted under torture ascribed his disappearance to the Jews, who allegedly wanted the victim’s blood to bake matzos – an anti-Semitic trope familiar from the Middle Ages in Europe, which the French consul brought into play.

Most European citizens were legally under diplomatic protection, which is why the French consul was able to have a direct influence on the investigations. A few Christians played along, hoping for economic advantages over Jewish competitors. The Islamic governor of Syria, on the other hand, refused to agree to the death penalty being applied.

The affair attracted much attention in Europe and resulted in a campaign by international Jewish dignitaries. This may have succeeded in securing the release of the convicts, but it also damaged relations between the two religious groups.

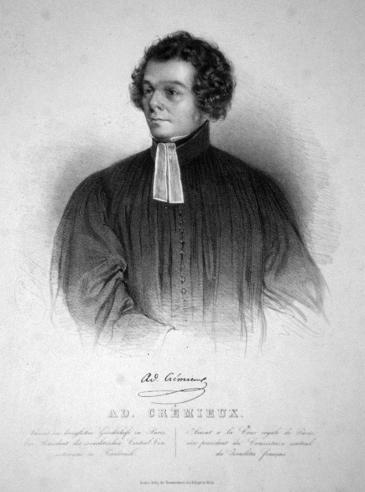

In North Africa too, the Jews had more to fear from European settlers under French colonisation than they did from their Muslim neighbours. A decree issued by the French justice minister, Adolphe Crémieux, drove a wedge between the religious groups from 1870 onwards. With the stroke of a pen, Crémieux made all Algerian Jews French citizens, without them having asked for this. By contrast, it was almost impossible for Muslims to obtain full citizenship, even though Algeria was French territory. Crémieux also helped to found the Alliance Israélite Universelle, an influential organisation headquartered in Paris, which ran schools first in North Africa and then in the Ottoman Empire, to “civilise” the Jewish population, whom they regarded as backward, to European standards. In so doing, the Jews were alienated from their neighbours in terms of language, habits and qualifications.

Adolphe Crémieux was the son of a Jewish silk merchant from Nîmes. He qualified as a lawyer and was later made France’s minister of justice. According to Peter Wien, a decree he issued in 1780 drove a wedge between Muslims and Jews in Algeria: “With the stroke of a pen, Crémieux made all Algerian Jews French citizens, without them having asked for this. By contrast, it was almost impossible for Muslims to obtain full citizenship, even though Algeria was French territory”

Loyal patriots

Until the fall of the empire, most Ottoman Jews remained loyal patriots. In the fields of economics, politics and culture, Jews, Christians and Muslims were closely linked, living side by side in modern residential areas and meeting in schools, chambers of commerce and freemasons’ lodges. After the First World War, the younger generation fought in political parties for a socialist order without religious barriers or for the liberation of the Arab nation from imperialism.

The number of anti-Jewish attacks in Arab countries increased during the 1930s with resistance to Zionism in Palestine. The idea of having to cede to Jews land that had been under Muslim rule for more than a thousand years seemed absurd. What’s more, the Zionist project was also under the protection of the hated British colonisers.

When Lord Balfour made his famous declaration in 1917, expressing the British government’s support for the establishment of a “Jewish homeland” in Palestine, the British foreign minister himself probably didn’t believe it was something that could be achieved.

However, it took the Zionists only two decades to develop a complex and powerful organisation in Palestine. The growth in population size as a result of immigration raised the pressure from the Jewish community on Palestinians until the outbreak of the Palestinian Revolt in 1936, which made the Palestine question a pan-Arab issue.

By the time British soldiers had put down the uprising shortly before the Second World War, Palestinian society was shattered and its ruling elite broken, imprisoned or in exile. The Palestinians have never recovered from the failure of the revolt.

One of the exiles was the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Amin al-Husseini. Even though it was the British who put him in this influential office in 1921, he still became one of their fiercest opponents. It was his propaganda in the 1930s that made the Temple Mount, with the Dome of the Rock and the al-Aqsa mosque, into a symbol of the Zionist threat to Islam’s holy sites for Muslims worldwide.

For its part, Zionism stood for the West’s neo-imperialistic aspirations for power over the Islamic world – a message that could be used by religious militants, secular radicals and nationalists alike. While still in Palestine, Amin al-Husseini was already in contact with German diplomats. In 1941, they finally brought him to Berlin, where he offered his services to the Nazis until the end of the war. And although his radio speeches were broadcast in Arabic to the Middle East and attracted much attention, they didn’t trigger the anti-British uprisings that the Germans were hoping for.

The openly anti-Semitic speeches and Nazi propaganda texts contained the same readings of the Koran that Islamic fundamentalists use today. Isolated anti-Jewish verses were taken out of context and combined with European anti-Semitic slogans to provocative effect.

It is questionable, however, whether the mufti actually wrote his radio speeches himself. German specialists, some of whom were Orientalists and were familiar with the Koran, manufactured the anti-Semitic connections themselves. This anti-Semitic interpretation of certain Koranic verses taken out of context was still unknown in the Middle East at that time.

Grand Mufti of Jerusalem Amin al-Husseini. A fierce opponent of the British in Palestine, al-Husseini arrived in Berlin in 1941. From there, he broadcast openly anti-Semitic radio speeches in Arabic to the Middle East with the support of the Nazis until the end of the war. Although they attracted much attention, the speeches didn’t trigger the anti-British uprisings that the Germans were hoping for

Most Arab thinkers were opponents of the Nazis

There is every indication that the mufti became an unscrupulous anti-Semite during his time in Berlin. He used his connections with Himmler to try to prevent Jewish children from Bulgaria, Romania and Hungary emigrating to Palestine. He knew about Auschwitz, even if there is no proof that he ever went there himself. After the war, he was used in Egypt as a figurehead for the Palestinian national movement, but he had little influence. He never set foot in his homeland again.

Most of the Arab world’s intellectuals remained opposed to the Nazis until the end of the Second World War. Although Germany was fighting the detested colonial powers of Great Britain and France, few people were under the illusion that a victory of the Axis powers would bring advantages for the Arabs in the Middle East.

The only outbreak of extensive anti-Jewish violence by Arabs occurred in Baghdad in 1941. After the defeat of a pro-German coup in a short war, a mob used the power vacuum left by the British occupation and ran amok in the streets of the deprived Jewish quarter, murdering, raping and looting. Members of a youth organisation influenced by the Mufti and German propaganda were involved. Up to 200 Jews died.

Many Muslims opened their doors to their Jewish compatriots. In places where Muslims and Jews knew each other, help was given. It was strangers who looted and committed the murders.

From the end of the Second World War onwards, however, when the conflict in Palestine began to intensify, things began to change. The Arab public began to accept Western anti-Semitic agitation indiscriminately.

The wars between Jews and Palestinians, and later between Jews and other Arabs, brought the trauma of expulsion to a majority of the new Israeli state’s Palestinian population. This trauma became a symbol of two hundred years of Western hegemony over the Islamic world – and not just for Arabs. These things do not excuse anti-Semitism or justify violence against Jews, but nor do they originate in the history of Islam.

© Süddeutsche Zeitung 2018

Translated from the German by Ruth Martin

Reprinted with author’s permission from Qantara.de

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved