Co-Authors: Doug Marcy, Gregory Dusek, John J. Marra, Matt Pendleton (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Center for Operational Oceanographic Products and Services1, NOAA Office of Coastal Management2, NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information3, The Baldwin Group, Inc.)

[ Full paper with charts and references is at the NOAA site in PDF. The following is an excerpt:]

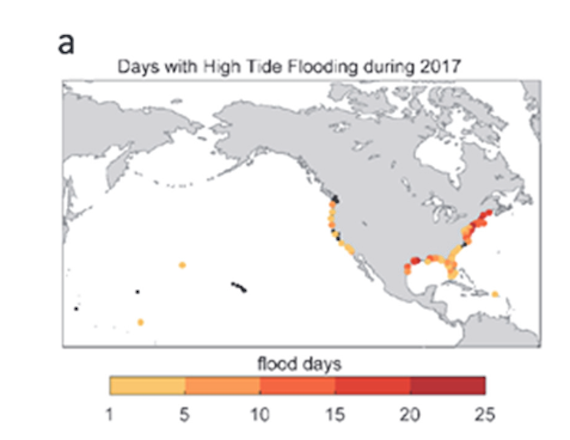

In 2017, the nation‐wide average annual frequency of high tide flooding as measured at 98 National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) tide gauge locations along U.S. coastlines hit an all‐time record of 6 flood days. More than a quarter (27) of the locations (Alaska sites were not included in this study) tied or broke their individual records for high tide flood days. Regionally, high tide flooding in 2017 was most prevalent along the Northeast Atlantic and Western Gulf of Mexico Coasts in response to active nor’easter and hurricane seasons.

Yearly records include 22 days in Boston, MA3 and Atlantic City, NJ4 and 23 days in Sabine Pass, TX and 18 days in Galveston, TX. Flood frequencies were also at record levels along parts of the Southeast Atlantic and Eastern Gulf, including 14 days at Bay Waveland, MS and 6 days each in Fort Myers, FL, Cedar Key, FL and Dauphin Island, AL. High tide flood frequencies were less in other U.S. regions, though San Diego, CA5 experienced a record‐breaking 13 days.

Mild El Niño conditions are predicted during late 2018 and into 2019, which may result in higher than expected flood frequencies (e.g., above trend values) at about half (48) of the locations, primarily along the West and East Coasts. As a whole, high tide flood frequencies during 2018 are predicted to be about 60% higher (median value) across U.S. coastlines as compared to trend values at the start of this century (i.e., year 2000).

Along the Northeast Atlantic and Northwest Pacific Coasts (where steeper topography often buffers the extent of impacts), 5‐6 days (median values) are predicted or a 100% and 10% increase since 2000, respectively. Along the flatter and more‐vulnerable Southeast Atlantic and Gulf Coasts, about 2‐3 flood days are predicted in 2018 or a 160% and 50% increase since 2000, respectively. Along the Southwest Pacific Coast about 2 days of high tide flooding are predicted (70% increase). Little or no tidal flooding is expected (as in all cases, not considering wave or rainfall effects) within the Caribbean, Hawaii or U.S. Pacific Islands (Kwajalein Island being an exception).

If high tide flooding in 2018 follows historical patterns, flooding will be most common during the winter (Dec‐Feb) along the West Coast and the northern section of Northeast Atlantic Coast in response to winter storms and more‐predictable monthly highest astronomical tides (predicted tides). Along the Gulf and along much of the Atlantic Coasts, flood patterns are less predictable and occur usually in response to weather effects.

Flooding is, however, most common during the fall (Sep‐Nov) when the mean sea level cycle peaks, and more often during monthly highest predicted tides in some Southeast Atlantic locations. Breaking of annual flood records is to be expected next year and for decades to come as sea levels rise, and likely at an accelerated rate (Sweet et al., 2017b).

Already, high tide flooding that occurs from a combination of high astronomical tides, typical winter storms and episodic tropical storms has entered a sustained period of rapidly increasing trends within about 2/3 of the coastal U.S. locations (Sweet et al., 2018). Though year‐to‐year and regional variability exist, the underlying trend is quite clear: due to sea level rise, the national average frequency of high tide flooding is double what it was 30 years ago . . .

3a

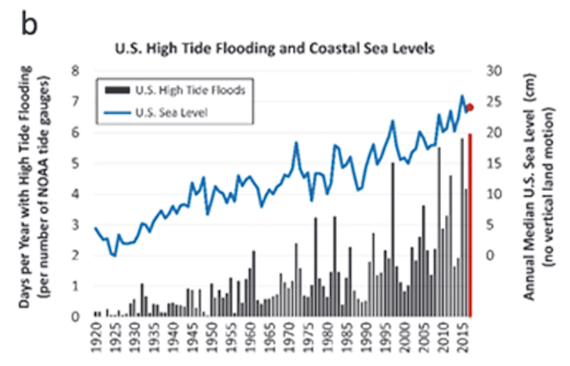

3a

3bJune 6, 2018 5 Figure 3: a) Number of days with high tide flooding using the nationally consistent flood severity thresholds (Figure 1a) at 98 NOAA tide gauges. Black dots are locations without a flood during 2017. b) Average high tide floods per year (black bars) through 2017 with 1920‐2016 data from Sweet et al. (2018) and the annual median coastal ocean level (blue line) through 2017 with local vertical land motion removed using estimates from Sweet et al. (2017b) for locations shown in a). 2017 sea level and flood frequency values in b) are shown in red. High (low) sea level and flood frequency years in b) such as during 1997 (1988) often correspond to El Niño (La Niña) conditions.

When high tide flood frequencies along the entire U.S. coastline are averaged (Figure 3b), the 2017 national average of 6 days . . . is record breaking. Rising ocean levels along the U.S. coastline (Figure 3b, blue line) of about 2 mm/year since 1920 are driving (along with local land subsidence) a rapid increase in U.S. high tide flood frequencies. The U.S. average high tide flood frequency is now 50% greater since 2000 and 100% greater than it was 30 years ago . . .

High tide flood frequencies continue to rapidly increase . . . in 2018, they are predicted to be about 60% higher (median value) across U.S. coastlines as compared to frequencies typical in 2000 under ENSO neutral conditions . . . Flood frequencies are rising the fastest along the Southeast Atlantic Coast (median value of 160%). Rapid increases are also occurring along the Northeast Atlantic (100%), the Eastern and Western Gulf Coasts (about 50%). The marked increase in high tide flooding along the Southeast Atlantic versus the Northeast Atlantic Coast, for example, is problematic as topography along the Southeast Atlantic is flatter and more low lying, which exposes more infrastructure and populations to flooding . . . Along the Southwestern Pacific Coast, flood frequencies are predicted to be about 70% higher in 2018 than in 2000 due to the predicted mild El Niño . . .

Acknowledgements The authors acknowledge the NOAA Center for Operational Oceanographic Products and Services Data Processing Team for verifying the hourly water level data for the stations presented in this report and the NOAA Office of Coastal Management for mapping of the nationally consistent flood thresholds.

Via NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information

Citation:

Citing the complete report: Sweet, W.V., D. Marcy, G. Dusek, J. J. Marra, M. Pendleton, 2018: 2017 State of U.S. High Tide Flooding with a 2018 Outlook. Supplement to State of the Climate: National Overview for May 2018, published online June 2018, retrieved on June 7, 2018, from https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/monitoring-content/sotc/national/2018/may/2017_State_of_US_High_Tide_Flooding.pdf

NB: Climate change and sea level rise are caused by humans burning fossil fuels to drive their cars, heat and cool their homes, power factories, and for certain agricultural and building techniques. – JC

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved