Baghdad (Niqash.org) – There are anti-government protests in Iraq every summer. But the recent batch are different, and in ways that could hinder any resolution.

The protests that have been rocking the Iraqi political establishment for almost a month now began when dozens of unemployed young men from the village of Bahila, on the outskirts of the southern city of Basra, gathered outside an oil company premises demanding jobs. The protests then spread to the city centre and widened their scope, with participants demanding better state services and regular water and power supplies.

Protests in Najaf.

Protests are expected in Iraq in summer. It’s so hot that a lack of potable water and power to cool things down, or keep food, is enough to drive people onto the streets in anger. But these protests – which spread from Basra to other provinces, including the capital Baghdad – are different from past ones in several ways. For one thing, they appear to be spontaneous and leaderless, their demands are many, often non-specific and in some cases, unrealistic. And if the protestors have one thing in common, it is their distrust of, and lack of confidence in, the whole of the Iraqi political establishment. They are not targeting any one party or sector; basically, they don’t like anyone.

If we were asked to choose between taking power or supporting their demands, we would choose protests.

All of these factors make it unlikely that the protestors will be able to achieve what they want. In fact, it may hamper them in the long run.

The lack of leadership makes it hard to find anyone to negotiate with. Some of the demonstrators said they were heading to Baghdad, having organised delegations to meet with the current prime minister, Haider al-Abadi. But as soon as they said this, other demonstrators were quick to announce that the delegations going to Baghdad did not represent them.

In this case it’s hard to negotiate a solution, let alone following up on any plans.

The absence of any leadership could see the protests fade away. There is also the danger that other less well-intentioned parties could exploit the protests.

During last year’s anti-government demonstrations, the leaders tended to be members of civil society groups and secular movements. They created a culture of protest going back to 2010. The other leader of that movement was the influential Shiite Muslim cleric Muqtada al-Sadr and a large number of his followers.

But all of those former organisers are now somehow tainted by their recent win in the federal elections, held in May this year. They are now seen as part of the political process and therefore, unable to participate in this round of anti-government anger.

Al-Sadr, whose alliance won the most seats in the next parliament, had proposed postponing government formation negotiations in order to respond to the demonstrators. But when al-Sadr tried to send a delegation of his supporters to speak with the Basra demonstrators, the Basra locals refused to receive the group. It was an unexpected rejection.

“Winning has its downsides,” says an MP for al-Sadr’s alliance, who is likely to be awarded a seat in Baghdad’s parliament; he could only speak anonymously as he was not supposed to comment on the situation. “The protestors believe we have become powerful in the country’s politics before the government has even been formed, or the parliament chosen. We do support the demonstrators and if we were asked to choose between taking power or supporting their demands, we would choose protests rather than becoming part of a government that is unable to provide the necessary services,” he told NIQASH.

Another unusual thing about the current protests, and a sign that the demonstrators are opposed to all kinds of elites in Iraq: They were even criticizing the country’s highest Shiite Muslim religious authority, Ali al-Sistani, who is usually not an acceptable target. Protestors had banners criticizing al-Sistani and asking why he had not spoken in support of the protests during the first week they happened.

They are lying to us. This promise is worth nothing.

Al-Sistani finally spoke out about the protests during last Friday’s sermons. He called upon demonstrators to keep up the pressure on the country’s politicians and demanded that the new government be finalized as quickly as possible, and that it be headed by a “strong and brave” prime minister. Al-Sistani also called on the politicians to think carefully about what they did in the past.

By talking about the past, al-Sistani was thought to be referring to the Sunni-Muslim-majority anti-government protests of 2013. The government did not respond to the protestors’ demands, or it clamped down violently – all of which enabled extremists to weaponize the protests. This can be seen as part of the reason for the rise of the extremist Islamic State group in Sunni Muslim areas.

Angry protestors also attacked and set alight the headquarters of Shiite Muslim political parties in southern Iraq. They did not appear to care which offices they damaged and even attacked the headquarters of the Shiite Muslim militias. Until just a few months ago the latter had been revered – and in many cases, considered above criticism within their own communities – for fighting the extremist group known as the Islamic State, and sacrificing their lives to do so.

Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi is a more obvious target for the protestors and is often criticised. But over the past three weeks, his acting government – in power until the formation of the next one – has tried rapprochement. Al-Abadi travelled to Basra but was unable to get very far as he was besieged by angry locals. He later decided to receive delegations in Baghdad instead.

Protests in Dhi Qar

To appease the protestors, al-Abadi has fired his minister of electricity and also promised the creation of thousands of new jobs. The government has also tried to engage influential local personalities – including community and tribal leaders and local politicians – to help restore peace.

Unfortunately nobody believes the government. “They are lying to us,” Abdul Ridha al-Rubaie, a community leader in Basra, told NIQASH. “Months ago, when the budget was being discussed, the government announced that it would not be able to create jobs because of the financial crisis in Iraq. Now it is suddenly offering thousands of jobs. But if it is really unable to create jobs – as they said previously – then this promise is worth nothing.”

All this pressure from the demonstrations, as well as al-Sistani’s reproach, has meant that Shiite Muslim political parties are renewing attempts to try and form a government. The political elites of Iraq are currently riven by infighting.

Nonetheless they also remain confused. They’ve been having to try and negotiate with angry mobs and deal with al-Sistani’s call to form a government of technocrats that can change the country for the better, rather than one based on Iraq’s controversial quota system. Some political parties have even stopped saying that one of their members should get the job of prime minister because they know it angers those on the street.

And now they must deal with the even more difficult part: Iraq has never formed a government that ignores the quota system before. To take a new untried route to power, makes things more difficult. And despite ongoing calls to hurry the process of government formation up, it is quite possible that doing so according to al-Sistani’s call, will delay it even further.

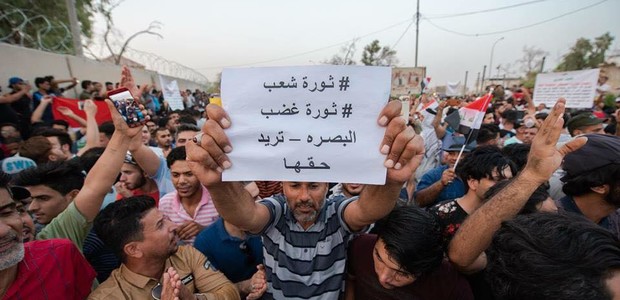

Featured Photo: A demonstration in Basra. The sign says: “The people’s revolution. A revolution of anger. Basra demands its rights.”

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved