Among the anecdotes told in the early biographies of the Prophet Muhammad is one about him being harassed by his immediate neighbors in Mecca, in roughly the period 614-622. One way they bothered him was to throw sheep offal through the window of his home in Mecca where he lived with his first wife, Khadija. `Abd al-Malik Ibn Hisham (d. 7 May 833) edited the earlier biography of Muhammad ibn Ishaq (died sometime in the 760s). In his translation of Ibn Hisham, Alfred Guillaume gives this passage to set the scene (Life of Muhammad, p. 191; Ar. 276-77):

- “Those of his neighbors who ill treated the apostle in his house were Abu Lahab [and others…]

“I have been told that one of them used to throw a sheep’s uterus at him while he was praying; and one of them used to throw it into his cooking-pot when it had been placed ready for him. Thus the apostle was forced to retire to a wall when he prayed.”

Then Ibn Hisham gives an anecdote for how the Prophet Muhammad responded to this petty harassment:

- “`Umar ibn `Abdu’llah ibn `Urwa ibn Zubayr told me on the authority of his father that when they threw this objectionable thing at him the apostle took it out on a stick, and standing at the door of his house, he would say, ‘O Banu `Abdu Manaf, what sort of protection is this?” Then he would throw it in the street.”

I tell this story in my book on Muhammad:

Muhammad: Prophet of Peace amid the Clash of Empires,

Available at Barnes and Noble

And Nicola’s Books in Ann Arbor

And Hachette

And Amazon

The biographers maintain that Muhammad’s own immediate relatives, including the Muttalib and Banu Hashim of the `Abd Manaf clan of Quraysh, decided to give him their protection even though they were pagans. It was more important to them that he was a kinsman than that he had what Mecca pagans considered strange religious ideas. Other clans of the Quraysh tribe in the city are alleged to have been militant pagans and to have objected to Muhammad’s denial of the reality of the gods. To a polytheist, a monotheist is a kind of atheist.

But, while the pagan clans gave protection to Muhammad and his followers, they couldn’t be everywhere all the time, and this anecdote represents the long-suffering Prophet as observing that they sometimes did not seem to be keeping him very safe from the mischief of enemies.

The Revisionist academic historians of early Islam, at least in their heyday of the 1970s through recent years, cast severe doubt on these anecdotes about the life of the Prophet, on the grounds that Ibn Hisham, for instance, was writing in the early 800s but Muhammad died in 632. Even if some of his material came from Ibn Ishaq, who was presumably collecting these anecdotes from roughly 100 to 130 years after the Prophet’s death, that still doesn’t get us very close.

Since all the evidence we had was literary, how did we really know that the Prophet lived in Mecca or that any of the people mentioned in the early sources really existed?

Skepticism is useful in academic study up to a point, since people who hold a particular view of what happened are pressed to clarify how exactly they know what they think they know, and what their sources are, and how primary they are. But there is a difference between healthy skepticism and denialism.

I agree that much in the later Muslim biographies of Muhammad is essentially folk stories and later elaborations and tall tales. My own rule of thumb is that if the story isn’t like anything in the Qur’an, then I reject it, or at least see no reason to accept it.

But this particular anecdote isn’t implausible on the surface, and the Qur’an does speak of the Meccan pagans insulting, taunting and harassing the Prophet and the early Believers. The Qur’an advises them to meet this behavior with good wishes and prayers of peace for their foes. So a sigh by the Prophet that his clan protection was imperfect would not contradict these passages of the Qur’an.

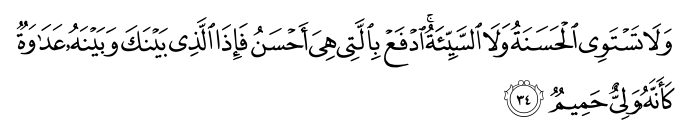

For instance, Qur’an 41:34 (Explanation/ Fussilat)

“Good deeds and wicked ones are not equal. Repel evil with a higher good, and your enemy will become your devoted patron.”

Arabic names of this period, as with Norse ones, are more a genealogy than a name. The anecdote about Muhammad’s reaction to being bothered in this way came from a man named “`Umar” (i.e. Omar). His father was `Abdu’llah, and his grandfather was the historian and jurist of Medina, `Urwa (d. 712 or 713). His great-grandfather, Zubayr ibn al-`Awwam (d. 656), had been a companion of the prophet.

Gregor Schoeler and Andreas Gorke have identified eight anecdotes about the life of Muhammad which were very widely related by early Muslims, and which they attributed to `Urwa ibn al-Zubayr, the grandfather of the `Umar who told the story about the sheep’s uterus. I compared these eight accounts to the Qur’an’s own narratives in my book, Muhammad: Prophet of Peace amid the Clash of Empires

And now for the big reveal. The Saudi scholar Mohammed Abdullah Alruthaya Almaghthawi (on twitter as @mohammed93athar) has been publishing on Twitter Arabic inscriptions found on rock faces around Medina, the Prophet’s adopted city from 622.

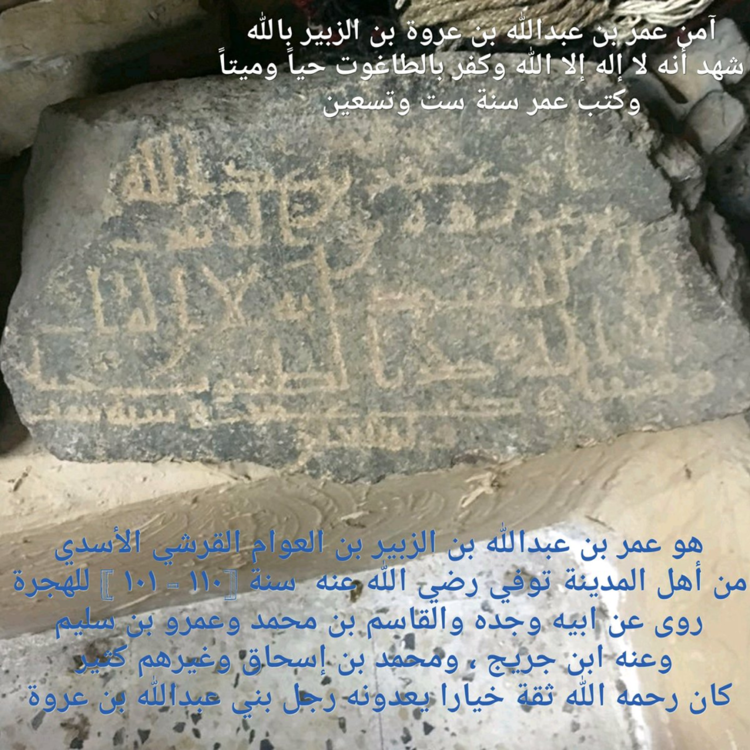

One of these inscriptions goes this way:

- “`Umar ibn `Abdu’llah ibn `Urwa ibn al-Zubayr has believed in God and bears witness that there is no God but God, and has denied [the idol] Taghut, both in this life and after death. `Umar has written this in the year 96.”

آمن عمر بن عبد الله بن عروة بن الزبير بالله شهد إنه لا إله إلا الله وكفر بالطاغوت حياً وميتاً وكتب عمر سنة ست وتسعين

96 AH, the Muslim calendar ran from mid-September of 714 to early September of 715. That is, this inscription claims to be from only 82 solar years after the death of Muhammad in 632. Some scholars think the Gospel of John was composed about 80 years after the death of Jesus.

The original tweet is here:

#نقوش_إسلامية لآل الزبير بن العوام رضي الله عنه #المدينة_المنورة

١ – نقش لعبدالله بن عباد بن حمزة بن عبدالله بن الزبير القرشي ثم الأسدي .

٢ – ثلاثة نقوش لسالم بن عبدالله بن الزبير رضي الله عنه .

٣ – نقش لعمر بن عبدالله بن عروة بن الزبير .

من متحف تركي الربيلي .#الخط_المدني pic.twitter.com/LUoRziTnkU— نوادر الآثار والنقوش (@mohammed93athar) May 24, 2018

This is the photograph of the inscription:

Mohammed Abdullah Alruthaya Almaghthawi, the Saudi scholar posting these inscriptions, gives `Umar’s date of death somewhere in the years 100 and 110 AH, i.e. 718-728 AD.

Ibn Ishaq was born in 704 and would have been 24 in 728. So it is entirely possible that he met `Umar and heard this anecdote from him in his youth in Medina.

Of course, this simple inscription does not prove that the anecdote of the Prophet being bothered with having sheep’s offal tossed at him has any truth to it, only that the alleged relater of the anecdote actually existed and was a Muslim.

The biographer Ibn Sa`d confirms that `Urwa ibn al-Zubayr’s eldest son was named `Abdu’llah, so that was the father of our `Umar.

`Umar is said to have heard stories of the prophet from his grandfather, the historian `Urwa, when he was young. He did not leave behind any children.

This inscription seems to be held in a regional museum in Saudi Arabia, named the Turki al-Rubayli Museum, which suggests that Saudi archeologists have looked carefully at it. I obviously cannot attest its authenticity, but do not see a strong reason to doubt it.

Al-Zubayr and his descendants are alleged by later historians to have played an important role in very early Islamic history. Al-Zubayr led a rebellion in 656 against the fourth Commander of the Faithful, Ali. His son `Abdullah (`Urwa’s brother, d. 692–not to be confused with `Urwa’s eldest son) rebelled against the Umayyad ruler Yazid, ironically at first in conjunction with Ali’s son Husayn (the grandson of the prophet). Both Abdullah and Husayn were killed by the Umayyads. `Urwa wasn’t political but must have sympathized with his brother. He burned many of his writings during that rebellion, which he is said later to have regretted.

The inscription by `Umar, `Urwa’s grandson, tells us nothing about politics but does say something about early Muslim piety in the first century of the faith:

- “`Umar ibn `Abdu’llah ibn `Urwa ibn al-Zubayr has believed in God and bears witness that there is no God but God, and has denied [the idol] Taghut, both in this life and after death. `Umar has written this in the year 96.”

It is interesting to me that the author of the inscription made a point of denying the existence of gods. Taghut seems to be an Ethiopian word for graven idols that was adopted into the Arabic of West Arabia (the Hejaz).

Maybe I am reaching and the inscription is formulaic. But I suspect that it indicates that North Arabian paganism continued to be practiced in rural areas of Arabia, Transjordan and Syria well into the Umayyad period. Hence, pious Muslims still found it important to distinguish themselves from polytheists and henotheists, who were around them.

The monk of northern Iraq writing in the 680s, John bar Penkaye had observed of Umayyad rule,

- “From every man they required only the tribute, and left him free to hold any belief, and there were even some Christians among them: some belonged to the heretics and others to us. While Mu`awiya reigned there was such a great peace in the world as was never heard of, according to our fathers and our fathers’ fathers.”

Elsewhere, he complained that under early Muslim rule, Near Eastern Christians were making friendships with Jews and engaging in commerce with infidels (pagans/Hellenes?).

See also for the survival of religions other than Islam in the Hejaz, Henry Munt, “No two religions”: Non-Muslims in the early Islamic Ḥijāz,” 2 Jun 2015, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies.

——

Advertisement

© 2026 All Rights Reserved

© 2026 All Rights Reserved