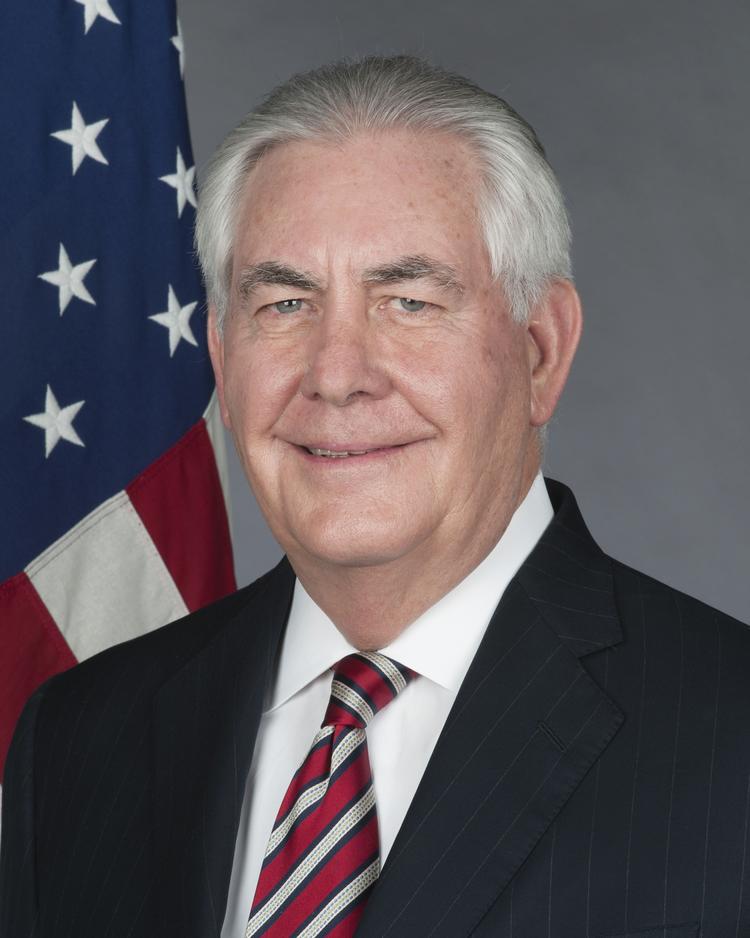

Alex Emmons at The Intercept interviewed two former State Department officials and one intelligence official who confirmed to him that in early June, 2017, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates had been on the cusp of invading Qatar, but were stopped by Rex Tillerson. Emmons suggests that Tillerson lost his job over his intervention, given the sway evil genius Yousef al-Otaiba (UAE ambassador in Washington, DC) has over Trump son-in-law Jared Kushner.

As I noted in a Nation article last February, high Qatari officials had repeatedly alleged that their intelligence told them of an impending Saudi invasion in June of last year.

Emmons speculates that a primary motive for the planned invasion was that Crown Prince Mohamed Bin Salman wanted Qatar’s $300 bn sovereign wealth fund and future revenues from the sale of Qatari natural gas. Saudi Arabia itself is blowing through its own dollar reserves and faces a bleak future if it does not repair its spendthrift ways or find a new source of income other than the failing oil business.

It is a plausible speculation. Otherwise, it is difficult to see what Saudi Arabia and the UAE could possibly get from this move, which has hurt them in world opinion. Mohamed Bin Salman has acted so erratically and recklessly that he has scared off foreign investors almost entirely. His plan for an Aramco Saudi IPO appears to be in severe trouble.

Of course, the cover story is that Qatar supports the Muslim Brotherhood and “terrorism” and its freewheeling Al Jazeera television channel provokes critical thinking in the Arab publics. In essence, the Saudi and United Arab Emirate absolute monarchies were afraid of the democratization that began during the 2011 Arab Spring youth movement, and have used their oil billions to crush it. Qatar was on the other side of that struggle, supporting moves toward electoral democracy and the inclusion of the Muslim religious right in politics, and crushing it would be the final nail in the coffin of any sort of popular liberties in the Arab world.

On the other hand, Emmons’ fine piece does unduly discount some other actors. Secretary of Defense James Mattis surely acted behind the scenes to protect the US-leased al-Udeid air base, from which 80% of US sorties against extremists in the region are flow. Mattis is said by some Qataris to have a special connection to al-Udeid Base and a special affection for Emir Sheikh Tamim Al Thani. In fact, a Mattis intervention with King Salman surely would have carried much more weight than one from Tillerson.

Then, many Qataris to whom I spoke when I was there the first half of this year were convinced that a Turkish parliament vote to allow sending troops to Qatar was what deterred the Saudis. (A couple hundred Turkish troops subsequently turned up in Qatar, putting some teeth into the threat).

In the end, I think the article is a little US State Department-centric. Tillerson no doubt played a role (and Exxon-Mobil will likely do well out of Qatar’s expansion of its natural gas exports).

But Mattis also likely swung into action, and he wasn’t thereafter sacked. And Turkey was enormously important.

The plot has failed, leaving the old Gulf Cooperation Council in permanent limbo, it seems to me. The Qatari stock market and the economy have completely recovered from the momentary wobble in confidence of summer 2017, and prognostications for the future are bright. Qatar has become a Singapore (which was cast out of Malaysia in 1965), though I think it will take time for the Qataris to adjust to that status. It isn’t a bad fate, if managed properly. I’ve been to Singapore several times, and it is nice.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved