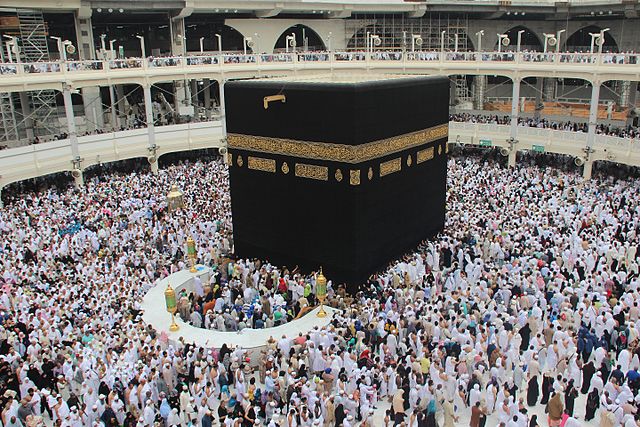

During the Muslim pilgrimage to Mecca, believers circumambulate the square ‘House of God’ called the Kaaba. It is said to have predated Islam, and to have been cleansed of idols by the Prophet Muhammad in January of 630, when the town of Mecca swung to his leadership by acclamation.

There is some new archeological evidence for the Kaaba in the form of Arabic rock inscriptions in Western Arabia, photographs of which have been published on Twitter. I should underline that this evidence was put up on Twitter by Abdallah Muslih Al-Thumali and Mohammed Almaghthawi, respectively. All I’m doing is reading my Twitter feed and am grateful to these intrepid rock climbers who are bringing us this new evidence.

The inscriptions have also been published: Sa’d bin Rashid, al-Suwaydirah : al-taraf qadiman, atharuha wa-nuqushuha al-Islamiyah, Riyadh, 2009.

Belief in sacred sites like the Kaaba was widespread in that part of the world from ancient times.

In the Hejaz and Transjordan, a sacred site was called in Arabic a ḥaram.

h/t Researchgate

In the Nabataean culture of roughly 300 BC through the Christianization of the 300s AD (after Constantine’s conversion of 312), such a sacred place or temple was called mḥrmt’ (mahramat?– we don’t have their vowels) in their sometimes Arabized Aramaic.

Thus we have the inscription:

d’ mhrmt dy bnh cnmw

which means “This is the consecrated place which PN built”

(M. O’Connor, “The Arabic Loanwords in Nabatean Aramaic,” Journal of Near Eastern Studies, Vol. 45, No. 3 (Jul., 1986), pp. 213-229, this phrase on p. 223).

ḥrm also meant sacred in the sense of inviolable. So tomb raiders were warned by Nabataean inscriptions that a grave and its inscriptions are sacrosanct (ḥrm) and not to be disturbed.

There was a Roman Greek witness to Arab sacred spaces from the 500s AD. I have written,

- ‘A Roman ambassador to the Arabs, Nonnosos, observed a few decades before Muhammad’s birth that they “have a sacred meeting-place consecrated to one of the gods, where they assemble twice a year. One of these meetings lasts a whole month….[T]he other lasts two months.” He added, “During these meetings complete peace prevails, not only amongst themselves, but also with all the natives; even the animals are at peace both with themselves and human beings.”’

Emperor Justinian and his Court, h/t Metropolitan Museum, NYC.

I discuss this issue in my new book,

Muhammad: Prophet of Peace amid the Clash of Empires (2018)

Available at Barnes and Noble

And Nicola’s Books in Ann Arbor

And Hachette

And Amazon

The Qur’an (Stories 28:57) says that people in Mecca have been provided with a “safe sanctuary” or “secure consecrated place” (ḥaraman āminan), which has been taken to refer to the Kaaba. As Nonnosos said, such places were “secure” because feuding and fighting were forbidden in their precincts. In my recent book, I argue that Muhammad, as a member of the Banu Hashim clan, was part of the kinship group charged with servicing pilgrims to the Kaaba and making sure violence did not touch it. They would thus mediate feuds and make peace. That was the background out of which Muhammad came.

The Qur’an also on numerous occasions uses for it the phrase al-masjid al-harām (e.g. 5:2), probably meaning “the sacred temple.” The Qur’an uses “masjid” for any place of worship, including synagogues and churches, which confused later commentators, since it is the origin of the word “mosque” and came to mean a Muslim place of worship. The Arabic masjid in the time of the Qur’an, however, had a wide signification. The cognate msgd in Aramaic means altar.

In the Jordanian city of Petra north of the west Arabian area called “the Hejaz” from which Muhammad hailed, archeologists in the 1990s found Greek papyrus rolls in the basement of a church. Ahmad al-Jallad has found that in the Petra Papyri, produced in the 500s AD in Greek, the Arabic word masjida is mentioned, with the ‘a’ at the end showing it was a loan word from Aramaic.

1/ #Spanish mezquita ‘mosque’ supposedly comes from Andalusian Arabic ‘masgid’, but why does it end in /a/? And why does it lack the article ‘al-‘ that characterizes Arabic loans in Spanish? Here is an interesting story involving the #Aramaic of the #Nabataeans! pic.twitter.com/jEwkXqJ9TX

— Ahmad Al-Jallad (@Safaitic) November 17, 2018

So here’s what’s new:

A recently discovered rock inscription from near Ta’if dated 78 AH (began March 30, 697), published by Abdallah Muslih Al-Thumali, mentions “al-masjid al-ḥarām,” likely a reference to the Kaaba.

نقش نادر مؤرخ عام 78 ، في حمى النمور بالطائف، وثقه الدكتور ناصر الحارثي رحمه الله ، ودلني على الموضع عبدالله النمري. وكاتبه الريان بن عبدالله ، وفي نهاية النص : كُتِب هذا الكتاب عام بني المسجد الحرام ، لسنة ثمان وسبعين .

ولعله يقصد بناء الكعبة زمن خلافة عبدالملك بن مروان . pic.twitter.com/vX5senXOwW— أ.د .عبدالله مصلح الثمالي (@thoomaly11) March 12, 2018

It says at the end, “this inscription was written in the year when construction work was done on the sacred shrine (al-masjid al-ḥarām) in the year 78 [697-8].”

The publisher of this photograph says that he may be referring to the refurbishing of the Kaaba carried out by the sixth Umayyad caliph, `Abd al-Malik b. Marwan (r. 685-705).

Note that this inscription is only 65 solar years after the death of Muhammad. It is as close to him as we are, in 2019, to 1954, when Elvis Presley’s career began.

Given the lateness of our manuscript sources on early Islam– with Ibn Ishaq’s biography of the Prophet allegedly being from the 760s, some 130 years after Muhammad’s death in 632, and existing only in early ninth-century redactions, this inscription may be our first mention of the Kaaba outside of the Qur’an (which Muslim tradition dates 610-632).

Another recently discovered rock inscription from the Hejaz in madani script has been published on Twitter by the renowned Saudi archeologist Mohammed Almaghthawi. It is likely from the second century A.H. (c. 718 – 815 AD) and inscribed by one Maysara b. Ibrahim, who identifies himself as “servant of the Kaaba” (khādim al-ka`ba).

#نقوش_إسلامية تنشر لأول مرة من بادية #المدينة_المنورة :

نقش لخادم الكعبة ميسرة ابن إبراهيم رحمه الله ورضي عنه

– حسبي الله

وكتب

ميسرة بن إبراهيم

خدم / خادم الكعبة .#الخط_المدني pic.twitter.com/DEe6eXCCje— نوادر الآثار والنقوش?? (@mohammed93athar) February 5, 2019

Almaghthawi and his colleagues have found thousands of inscriptions in the Hejaz, especially around Medina, that appear to be from the first and second centuries of the Hijra (622-815 AD). These epigraphic witnesses to early Islam promise a revolution in our understanding of the subject.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved