By Joseph J. Gonzalez | –

Violence erupted at the Venezuela-Colombia border over the delivery of humanitarian aid to Venezuela, killing four people and injuring 24 on Feb. 22.

U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo warned Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro that his “days are numbered,” and Trump officials reiterated that the U.S. is considering all options, including military action, to address Venezuela’s crisis.

Almost 80 percent of Venezuelans disapprove of Maduro, who was reinaugurated for a second six-year term in January after an election widely seen as fraudulent. Since taking power in 2013, he has led Venezuela into a deep economic crisis.

In late January, opposition leader Juan Guaidó declared Maduro a “usurper” and swore himself in as the country’s rightful president. More than 50 countries – including the United States, Europe and most of Latin America – want to replace Maduro’s regime with a Guaidó-led government.

Despite near global condemnation of Maduro, any U.S. intervention in Venezuela would be controversial. The United States’ long history of interfering in Latin American politics suggests that its military operations generally usher in dictatorship and civil war – not democracy.

AP Photo/Rodrigo Abd

The Cuban-US Cold War

Cuba, the focus of my history research, is a prime example of this pattern.

U.S.-Cuban relations have never recovered from President William McKinley’s intervention in Cuba’s war for independence over a century ago.

Before waging what in the U.S. is known as the Spanish-American War in 1898, McKinley promised that “the people of the island of Cuba” would be “free and independent” from Spain and that his government had no “intention to exercise sovereignty, jurisdiction or control over said Island.”

In the end, however, Cuba’s independence from Spain meant domination by the United States.

For 60 years after the Spanish-American War, the White House made repeated military and diplomatic interventions in Cuba, supporting politicians who protected U.S. economic interests in sugar, utilities, banks or tourism and who backed American foreign policy in the Caribbean.

By 1952, when the U.S.-backed Fulgencio Batista overthrew President Carlos Prío Socarrás, Cuba’s government had effectively become protectors of American businesses, according to my research. Batista had a warm relationship with both Washington, D.C. and the American organized crime groups that used to control Havana’s tourist industry.

A communist revolution led by Fidel Castro overthrew Batista’s military junta in 1959. Castro decried the “imperialist government of the United States” for turning Cuba into an “American colony.”

The Kennedy administration’s trade embargo against Cuba and the disastrous 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion – in which the U.S. military trained Cuban dissidents in an attempt to unseat Castro – only pushed Cuba further into the orbit of Soviet Russia.

For the past six decades, the U.S. and Cuba have remained locked in a Cold War, with a brief thaw under President Barack Obama.

AP Photo

Anti-communist coups

Fearing that communism would spread across the hemisphere, the U.S. government repeatedly interfered in the politics of Latin American nations during the Cold War.

In 1954 the CIA worked with elements of the Guatemalan military to overthrow elected President Jacobo Árbenz, whom U.S. policymakers considered dangerously left-wing. Decades of dictatorship and civil war followed, killing an estimated 200,000 people.

A peace agreement in 1996 restored democracy, but Guatemala has yet to recover economically, politically or psychologically from the bloodshed.

Then there is Chile’s U.S.-supported coup d’etat. In 1973, the U.S. government covertly assisted right-wing elements of the Chilean military in overthrowing the socialist president Salvador Allende.

General Augusto Pinochet took power with the quiet financial and political support of the United States. His dictatorship, which lasted until 1990, killed tens of thousands of Chileans.

The Dominican Republic and Panama

U.S. intervention in Latin America did not start or end with the Cold War.

During World War I, the United States was concerned that Germany could use the Dominican Republic as a base of military operations. So American troops occupied the Caribbean island from 1916 to 1924.

Though the American-led administration improved the finances and infrastructure of the Dominican Republic, it also created the national guard that helped to propel Gen. Rafael Trujillo into power. His 30-year reign was savage.

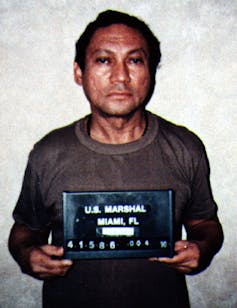

President George H. W. Bush’s 1989 invasion of Panama is the rare exception when U.S. intervention in Latin American affairs actually created stability.

Most Panamanians appear to have supported the 1989 U.S. military operation to remove the corrupt and brutal military strongman Manuel Noriega.

In the years since, Panama has enjoyed comparatively peaceful elections and transfers of power.

Anti-Americanism in Latin America

On balance, though, U.S. military operations in Latin America have rarely brought democracy.

But they have created strong anti-American sentiment in the region, which leftist leaders from Fidel Castro to Hugo Chávez have adeptly harnessed to vilify their political opponents as mere U.S. puppets.

Support for the U.S. government is lower now than it has been in decades. Just 35 percent of Argentines, 39 percent of Chileans and 45 percent of Venezuelans view the U.S. favorably, according to the Pew Research Center.

President Maduro, too, has used anti-imperialist rhetoric. He denounces U.S. sanctions and other efforts to isolate his regime as a “gringo plot.”

A safer way to restore democracy

This history explains why a U.S. intervention in Venezuela would be viewed with skepticism. Though Maduro is unpopular, 65 percent of Venezuelans oppose any foreign military operation to remove Maduro, according to recent polling.

Rather than plan yet another coup d’etat, I believe U.S. efforts in Venezuela should support the work of the Lima Group, a coalition of 12 Latin American countries, including Mexico, Guatemala and Brazil, plus Canada.

The Lima Group has ruled out military force in Venezuela. Its pressure campaign to force him out peacefully has included diplomatically isolating his regime and asking Venezuela’s soldiers to pledge loyalty to Guaidó.

A negotiated settlement leading to Maduro’s voluntary departure from office is their ultimate goal.

Regional diplomacy is much slower than foreign intervention. But it avoids further bloodshed and reduces the role of anti-Americanism in Venezuela’s crisis.

It may also open a new chapter in the history of U.S.-Latin American relations – one in which the U.S. takes its lead from the region, and not the other way around.

Joseph J. Gonzalez, Associate Professor, Global Studies, Appalachian State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

——

Bonus video added by Informed Comment:

Aljazeera English: US, Russia rival bids for UN action in Venezuela blocked l Al Jazeera English

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved