By Robert Hassan | –

It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen. Winston Smith, his chin nuzzled into his breast in an effort to escape the vile wind, slipped quickly through the glass doors of Victory Mansions, though not quickly enough to prevent a swirl of gritty dust from entering along with him.

As novel-openers go, they don’t come much better than this one in George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four. See how the unexpected “striking thirteen” runs powerfully into the beginnings of characterisation and world-building in just two arresting sentences.

Shutterstock

Orwell knew that words could both grip the attention and change the mind. He wrote the book as the Cold War was becoming entrenched, and it was meant as an explicit warning on the nature of state power at that time.

The book still sells by the thousands, and is read by students who are compelled to do so. But it can be read voluntarily and profitably, and it can tell us a lot about contemporary politics and power, from Donald Trump to Facebook.

A world of ‘doublespeak’

Goodreads

Nineteen Eighty-Four became an instant classic when published in 1949. People could see in it a world that could easily become a reality. The memory of Nazi dictatorship was still fresh, the Soviet Union had erected the Iron Curtain, and the USA had the atomic bomb.

The novel’s setting is a dystopian Britain, which has become a part of Oceania, a region in perpetual war with the other super-regions of Eurasia and Eastasia. Oppression, surveillance and control are facts of life in a society ruled by the Party and its four Ministries of Truth, Peace, Plenty and Love.

It is a world of “doublespeak” where things are the opposite of what they appear; there is no truth, only lies – only war and only privation.

One of Orwell’s innovations is to introduce us to a new political lexicon, a “Newspeak” where he shows how words can be used and abused as a form of power. Words like “Thoughtcrime”, where it is illegal to have thoughts that are in opposition to the Party; or “unperson”, meaning someone who has been executed by the Party (e.g. for Thoughtcrime) will have all record of his or her existence erased.

Not only do we use many of these words today, but the manipulative function that Orwell described is still intact. For example, when Kellyanne Conway, advisor to US president Donald Trump, stated in 2017 that the Administration has its own “alternative facts”, she was indulging in “doublethink”: an attempted psychological control of reality through words.

Nineteen Eighty-Four became an Amazon bestseller following the election of Trump and the airing of this interview.

Within the corridors of Orwell’s Ministry of Truth, though, there’s a tiny flickering of real love that develops between protagonist Winston and co-worker Julia. They share unlawful thoughts about other possible ways of living and thinking, based upon vague and unreliable memories of a time before world wars and Big Brother and the Party.

But through its immense powers of surveillance and the efforts of the Thought Police, Big Brother knows everything, and soon the lovers are suspects. Winston is arrested and brought before O’Brien, the novel’s antagonist and a Party heavyweight who is openly cynical about the power structure of society. For him power is a zero-sum equation: if you don’t use it to keep others down, they will use it similarly against you.

There is much drama, suspense and even horror in Orwell’s book. He wrote about what he saw around him, but filtered it with an acute sensitivity to the innate fragility of civilisation. In 1943, when the plot-lines of Nineteen Eighty-Four were probably gestating in his head, Orwell wrote:

Either power politics must yield to common decency, or the world must go spiralling down into a nightmare into which we can already catch some dim glimpses.

1984 goes digital

These days, a lot of power politics circulates online. Orwell, who worked for the BBC during the war, was sensitive to the power of communications. What he calls the “telescreen” is essentially a surveillance device that “received and transmitted simultaneously”.

He writes of the device that “any sound that Winston made, above the level of a very low whisper, would be picked up by it; moreover […] he could be seen as well as heard”. Remind you of anything? Alexa or Siri and their ilk may be fads, but the technology now exists; and so then does a new kind of power.

Such power is contingent and shifting and does not always reside with governments.

Donald Trump wields a new digital power through Twitter and Facebook and can “speak to his base” whenever he’s angry, bored or overcome by impulse. But through ownership of new digital technologies, new actors – data corporations – have acquired old powers. These are the powers to manipulate, surveil, and influence millions of people through access to their data.

And their power in turn can be leeched by hackers, state-sponsored or independent. The complexity of political power today means we need to be more attuned to its changing forms, to more effectively strategise and resist.

Orwell’s “common decency” reference may now sound rather quaint. But its very absence in social media is a problem.

The algorithms that Twitter, Facebook and Google insert into our communications act essentially as “manipulation engines” that can cause division, favour extreme views, and set groups of people against each other.

Divide-and-rule is not their intention – getting you online in order to sell your data to advertisers is – but that is the effect, and democratic politics is the worse for it.

Understanding the nature of political power is even more important today than when Orwell wrote. Oppression and manipulation were “simpler” and more brutal then; today, social control and its sources are more opaque.

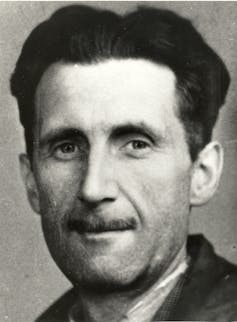

Wikimedia Commons

Orwell’s imperishable value as a writer is that he provides a template on the character of political power that tells us that we cannot be complacent, cannot leave it to government to fix, and cannot leave it to fate and hope for the best.

Things did not turn out so well for Winston Smith. Pushed to the limit by torture and brainwashing, he betrays Julia. And in his abject state he convinces himself, finally, of the rightness of the Party: “He had won the victory over himself. He loved Big Brother.”

The story ends there. But for Orwell the writer and activist, the struggle for Truth, Peace, Plenty and Love was only beginning.

Today, Nineteen Eighty-Four comes across not as a warning that the actual world of Winston and Julia and O’Brien is in danger of becoming reality. Rather, its true value is that it teaches us that power and tyranny are made possible through the use of words and how they are mediated.

If we understand power in this way, especially in our digital world, then unlike Winston, we will have a better chance to fight it.

Robert Hassan, Professor, School of Culture and Communication, University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

——

Bonus video added by Informed Comment:

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved