Ann Arbor (Informed Comment) – Istanbul has clapped back for democracy big time, electing as mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu of the secular Republican Peoples Party.

İmamoğlu had already won once, last May, with a margin of 15,000 votes. The increasingly dictatorial president, Tayyip Erdogan, of the center-right pro-Islam Justice and Development Party (AKP), argued that the margin was too close to call and alleged voting irregularities. Respecting electoral victories was a last little portion of democracy still adhered to by Erdogan, so his success in pushing the courts for a do-over in Istanbul (the country’s largest city and largest urban economy) was extremely worrisome. You had a fear that Erdogan would just go to appointing all the mayors.

But whatever Erdogan had in mind, it backfired on him disastrously. Early returns are suggesting that İmamoğlu will win by a whopping 800,000 margin in the city of 15 million.

Modern Turkey (which nowadays has a population of 80 million and is one of the top 20 economies in the world) has never been exactly a democracy. There have been elections since 1950, but often they were more or less stage managed by a small elite, and the results were regularly overturned, about once a decade, by the fiercely secular officer corps. The secular, centrist Republican People’s Party (CHP) was dominant, though not completely so. It claimed the heritage of reforming dictator Mustafa Kemal, and so was called Kemalist. Only a secular center was allowed, whether center-right (pro-business) or center-left (big public sector). Any signs of a socialist tendency (Bulent Ecevit) or a Muslim fundamentalist one (Necmettin Erbakan) were quashed by the military.

Like most of the Middle East, Turkey’s democracy has been impeded by the region’s strong urban-rural divide (though note that because of rural migration, some city neighborhoods vote like the rural areas). The divide is manifested in an urban preference for secularism, Europe and a strong public sector, and by a rural preference for Islam, Turkey first policies, and new opportunities for businesses and farmers in the hinterland.

Since 2002, the pro-Islam Justice and Development Party (AKP) has consistently won between 40 and 50 percent of the vote. But as a center-right party with a moderate religious appeal, it also attracts as a coalition partner the (secular) far right wing Turkish National Movement Party (MHP). Between the two of them, they have been able to secure a majority and often a super-majority in the national parliament for 17 years. Sometimes the AKP has been so popular that it had a big majority on its own. The central figure of the AKP, who has climbed over a lot of his partners’ bodies to get to the top, is current president, Erdogan.

I argue that in the zeros, the AKP was interested in political pluralism as a way of breaking the hegemony of the secular, urban-elitist Republican People’s Party (CHP). It also wanted to join Europe because of a conviction that the European Court of Human Rights would disallow the Kemalist restrictions on religion. Others have argued that Erdogan and his colleagues all along were plotting an illiberal “democracy,” with an almost dictatorial presidency and a tame press and parliament.

Certainly, in the past five years, Erdogan has marched the country to illiberalism, more or less Vladimir Putin style, using his natural majority of center-right voters to steamroll the opposition.

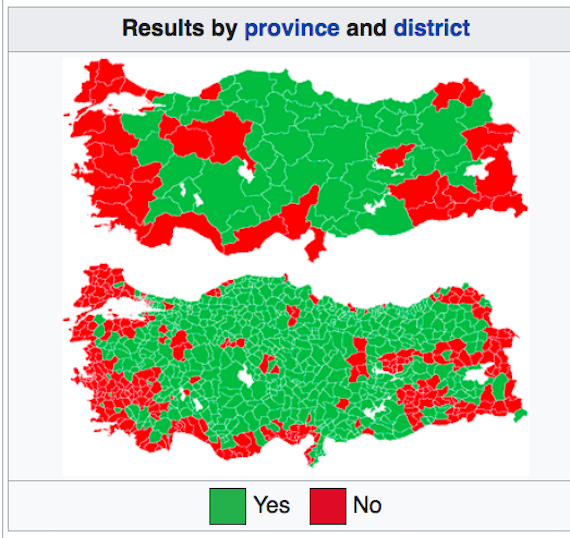

This map shows voting in the referendum a couple years ago on moving the country to a presidential system, which much weakened parliament and checks and balances. The red parts except in the southeast (where rural Kurds are unhappy with Erdogan’s crackdown on them) are the richer urban areas of Turkey, which tend to still vote Republican People’s Party and who are disturbed by Erdogan’s mix of pro-Muslim rhetoric, neoliberal favoring of a deregulated private sector, and planting of shopping malls everywhere he sees an open plot of land (including parks).

h/t Wikimedia

Ironically, the Justice and Development Party has long done well in municipal elections in Istanbul and Ankara, even though those cities voted against the party in national elections. The AKP was felt to be less corrupt and more efficient and pro-growth than its rival, the Kemalist CHP.

But after having been ensconced in power for 17 years, the AKP in general and Erdogan personally have become extremely corrupt and are losing the electoral advantage their clean image had offered them. Moreover, the AKP had a good run with economic expansion, but as with all Neoliberal waves, at some point there are diminishing returns–and problems of inequality and diminished social services come to the fore. This year the Turkish economy has not been doing well, and the Istanbul vote could well be a public reaction against slower growth.

In any case, Turkish democracy is still very ill– with attacks on journalists and academics and party corruption and a strong man president who faces very little in the way of checks. But with Imamoglu’s victory, the fever has perhaps dropped a degree or two.

—–

Bonus video:

Tic Toc by Bloomberg: “Erdogan Dealt Stunning Blow as Istanbul Elects Rival Ekrem Imamoglu”

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved