The great scholar Annemarie Schimmel quoted Arthur Jeffrey, the Australian scholar of Islam, to this effect: “Many years ago . . . the late Shaikh Mustafa al-Maraghi remarked on a visit to his friend, the Anglican bishop in Egypt, that the commonest cause of offence, generally unwitting offence, given by Christians to Muslims, arose from their complete failure to understand the very high regard all Muslims have for the person of their Prophet.” And Muhammad is his Messenger: The Veneration of the Prophet in Islamic Piety (Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, 1985).

It is not for nothing that Muhammad is the most popular name for male newborns in the whole world.

My latest book is a biography of the Prophet Muhammad drawn largely from the Qur’an itself, the scripture Muslims believe was inspired in him by God:

We have very little securely datable primary source evidence for the attitudes of the first generations of followers of the Prophet Muhammad. Almost all our accounts come from authors and editors of the ninth century, though some of these contain some texts and orally transmitted reports that may be earlier. Coins, a few papyri and thousands of rock inscriptions (most still not professionally published) are the only datable seventh and early-eighth-century sources. Of the published and tabulated early Muslim inscriptions in the Hijaz, Frédéric Imbert estimates that only 9% mention Muhammad. This result would be consistent with the thesis of Professor Fred Donner at the University of Chicago (Muhammad and the Believers) that the earliest believers in the Prophet Muhammad formed an ecumenical community of monotheists rather than being a sectarian movement. But it may also just be that rock inscriptions were used to seek blessings and security for the individuals who wrote them (something visible in the pre-Islamic Nabataean Aramaic inscriptions in southern Jordan and northern Hejaz, as well).

Some of the inscriptions about the Prophet Muhammad are eye-opening. One, discussed first, has been known since the 1930s. The other two below, one dated and the other from the first or second century of the Muslim calendar (which began in 622 in the Gregorian calendar), are fairly newly published and interpreted by the Saudi archeologist Mohammed Almaghthawi @mohammed93athar and Professor Sean W. Anthony @shahanSean.

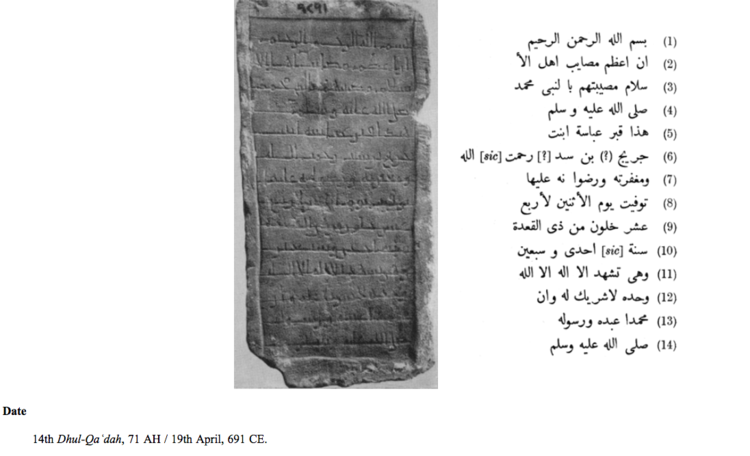

The first is reprinted at this Islamic Awareness site:

In the name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate.

The greatest calamity to have befallen the people of

Islam is the catastrophic loss of the Prophet Muḥammad,

may the blessings and peace of God be upon him.

This is the tomb of ʿAbbasa, daughter of

Juraij, son of Sad?. May the mercy,

forgiveness and good-pleasure of God be upon her.

She died on Monday four-

teen days having elapsed from Dhu al-Qa`dah

of the year one and seventy,

confessing that there is no god but God,

alone without any associate, and that

Muḥammad is his servant and his messenger,

may the blessings and peace of God be upon him.

This tombstone inscription is the earliest securely dated text of piety about the Prophet (691 is only 59 years after his death). It was initially published by H. M. El-Hawary, “The Second Oldest Islamic Monument Known Dated AH 71 (AD 691) From The Time Of The Omayyad Calif ‘Abd el-Malik Ibn Marwan”, Journal Of The Royal Asiatic Society, 1932, p. 289.

Its significance and dating is discussed by Jonathan E. Brockopp, Interpreting Material Evidence: Religion at the “Origins of Islam,” History of Religions, 2015 121-147.

The next dated attestation of piety toward the Prophet in an inscription was published by “The Desert Team” of archeologists in Saudi Arabia as an appendix to `Abd Allah `Abd al-`Aziz Sa`id and Muhammad Shafiq Baytar, Nuqush Hismá : kitabat min sadr al-Islam shamal gharb al-Mamlakah (al-Riyad : al-Majallah al-`Arabiyah, 2018).

The “Desert Team” photo was shared on Twitter by Mr. Almaghthawi.

It says, “O God, bless Muhammad the Prophet and accept his intercession for his community, and show us your compassion through him in the next world just as you showed us compassion through him in this world. This is being written by Bakr b. Abi Bakra al-Aslami at the completion of the year 80 [January 700].”

بارك الله فيكم على ماتبذلونه من جهود في توثيق هذا التراث القيم

وهذه قراءة للنقش :

اللهم صلي على محمد النبي وتقبل شفاعته في أمته

وارحمنا به في الآخرة كما رحمتنا به في الدنيا

وكتب بكر بن أبي بكرة الأسلمي تمام سنة ثمانين .والله تعالى أعلم بالصواب https://t.co/APZsJ65s2R

— نوادر الآثار والنقوش?? (@mohammed93athar) May 27, 2018

Professor Sean W. Anthony @shahanSean was the first to notice this inscription in English, having seen Almaghthawi’s photograph of it.

*important new discovery* An early, dated Arabo-Islamic inscription from Ḥismā

that mentions the the prophet Muhammad by name. This one is dated to the end of 80AH[=January 700CE]. A mere 7 decades after his death A quick English translation below: https://t.co/JO0E0IU8NR— Sean W. Anthony (@shahanSean) May 27, 2018

1) O Lord, bless Muḥammad [the Prophet] and accept his intercession on behalf of his community

2) And show us mercy through him in the Hereafter just as You have shown us mercy through him in this world

3) Written by Bakr ibn Abi Bakrah al-Aslamī at the completion of year 80— Sean W. Anthony (@shahanSean) May 27, 2018

These two dated inscriptions 59 and 68 years after the Prophet’s death (632) show a pious affection for him. The Muslim social circle of the convert from Christianity, `Abbasa the daughter of George who wrote her tombstone may have included an elderly person from the Hejaz who had moved to Upper Egypt and who had actually seen the Prophet as a child. Or they included persons who knew such women and men. The sense of loss is palpable.

The second inscription, from 700, speaks of Muhammad as an intercessor and as a source of divine compassion, twice. Once was the mercy God showed on human beings by sending him in this world as a Prophet. The second is his ongoing intercession from the hereafter.

There is a similarity between this idea of Muhammad as an intercessor and the late-antique Christian notion of exemplary saints interceding for the salvation of ordinary believers. But in Christianity the locus of the departed saint was bodily– the relic or the tomb. These inscriptions instead focus on the personality of the Prophet as a transtemporal figure who straddled this world and the next.

(Sixteenth and seventeenth-century Protestantism in Christianity and eighteenth-century Wahhabism in Islam, both critiqued the idea of intercession, but has been a widespread belief in those religions up to the present).

A third relevant inscription, this one undated, was also published by Mr. Almaghthawi and commented on by Professor Anthony.

The second inscription reads

1) اللهم

God

2) صلى على محمد

bless Muḥammad

3) النبى ويقبل

the prophet and accept

4) شفـ[ـا]ـعته وا

his intercession and pla-

5) جعل تماما من

ce Tamām among

6) رفقائه في

his companions in

7) الجنة آمين

Paradise. Amen pic.twitter.com/nEPhzzYTK9— Sean W. Anthony (@shahanSean) October 20, 2018

This rock inscription from near Medina, likely from the first or second century of Islam, calls upon God to accept the intercession of the Prophet for Muslims and asks God to make the author, Tamam, a friend or companion of the Prophet in heaven.

And here is a fourth such inscription (in addition to `Abbasa’s tombstone), from the first or second century AH. It says, “Our God, bless Muhammad, your servant, your messenger and the best of your creation. God give him blessings and peace.”

#نقوش_إسلامية تنشر لأول مرة من بادية #المدينة_المنورة :

نقش في الصلاة على محمد عبدالله ورسوله وخيرة خلق الله

صلى الله عليه وسلمروائع #الخط_المدني pic.twitter.com/A5RT0sXgWm

— نوادر الآثار والنقوش?? (@mohammed93athar) January 5, 2020

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved