By Arie Kruglanski, David Webber, Erica Molinario and Katarzyna Jaśko | –

While today’s news is full of stories about refugees and migrants to the U.S. from Central America, the plight of those particular refugees is only part of an international migration crisis that has been going on since 2015 and has driven 25.9 million refugees worldwide from their homes.

We study the psychological aspects of migration and have carried out a systematic study funded by the National Science Foundation of refugees from the Syrian civil war. Thirteen million refugees have fled the conflict that has ravaged Syria for the last eight years.

Some in the West have expressed concerns that Syrian religious extremists may migrate to the West under cover of the refugee crisis to do harm.

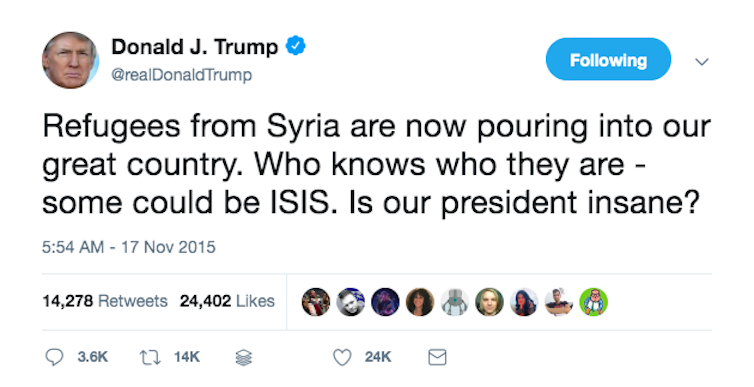

That attitude was reflected by presidential candidate Donald Trump in a Tweet from Nov. 17, 2015.

“Refugees from Syria are now pouring into our great country,” then presidential candidate Trump tweeted. “Who knows who they are – some could be ISIS. Is our president insane?”

Trump’s fear of Syrian refugees has been echoed in Europe.

A Pew Research Center study in 2016 found that 59% of European respondents believed that the coming of refugees would increase the likelihood of terrorism in their country.

So Syrian refugees are now marooned in refugee camps or other temporary venues, unable to migrate because of immigration policies borne, in part, of these fears.

Trump has essentially closed the borders to Syrians, with only 41 refugees admitted to the U.S. in 2018.

Numbers admitted were also down in Europe, previously the top destination for Syrian refugees.

We aimed to find out, through our survey, whether Syrian refugees pose a danger to the West.

Fear of the stranger

Fear of refugees may, to at least some degree, be psychological. Social scientists and philosophers have long noted people’s aversion to otherness of any kind, and the ubiquitous tendency to scapegoat and persecute minorities that differed from one’s own group in race, ethnicity or religion.

That fear has been cleverly exploited by politicians fueling anti-immigrant populism that catapulted xenophobic agendas to the forefront of national politics in various parts of the world, including Europe and the U.S.

Psychology’s ability to explain the pervasive fear of Syrian refugees does not necessarily mean that such fear is completely unfounded. Yet there are currently hardly any data about Syrian refugees’ state of mind, and on their interest (or lack thereof) in ideological and political causes of various kinds.

To address this gap in knowledge we carried out extensive surveys over the period between 2016 and 2017 with Syrian refugees temporarily living in Lebanon, Jordan and Turkey. We asked about their motivations, ideological commitments and immigration intentions. These data have been analyzed only now, and this is the first glimpse at our findings.

We wanted to know whether their political radicalism, if any, and their readiness to make sacrifices for religious and political causes would be related to their intention to immigrate to the West.

Refugee state of mind

Our study contradicts the idea that Syrian refugees are a danger to the countries to which they’ve immigrated.

We found that the majority of refugees wished to return to their home countries. And the overall level of radical religious and political beliefs among refugees was low.

Our study finds, moreover, that refugees inclined to move westward are typically pro-Western to begin with.

Were our respondents telling us the truth?

We believe so. Here’s why.

First, we took precautions to have our data collection carried out by Arabic speaking researchers from the region familiar with our respondents’ culture. They had credibility with the participants that outsiders would lack and so were less likely to cause respondents to dissimulate their feelings and opinions.

Second, we stressed to the respondents that their identity will remain private, which would make them feel more safe in giving honest answers.

Finally, our subsequent focus groups with Syrian refugees already in the West confirmed our survey results.

AP/Gogo Lobato

Images of the West

For the most part, these refugees saw the West as a land of stability, security and economic opportunity. Those expectations, rather than a desire to inflict harm, determined the refugees’ relocation intentions, our data suggests.

One refugee that we interviewed in Germany described her expectations prior to leaving for the West: “I heard people talk about how things will be easy and how we will be welcomed and they will arrange us houses, monthly salary and help us finding jobs just like in USA.”

Strikingly, in all our samples, radically leaning respondents decidedly preferred to go home rather than migrate to the West. Their reluctance to go West was highly correlated with their perception that neither their basic needs for security and comfort nor their significance needs for respect and status are likely to be met there.

These individuals were not big fans of the West, and felt uncomfortable with the prospect of spending their life there.

Contrary to the fear that the refugees’ intentions are to pour westward and potentially stir things up, our survey showed that refugees with extreme religious and political views were among the least likely to want to move West and among the most likely to want to return to heir homeland and pursue their ideological ends there.

The hope of a better life

The concerns of refugees who wanted to relocate to the West were largely personal and pragmatic.

Their motivation to immigrate to the West was driven by hopes that it is the place where their basic needs for security and subsistence and their significance needs for status and respect would be met. Those expectations of fulfillment and satisfaction in the West, our data suggest, determined the refugees’ relocation intentions.

From the results of our survey, the danger that the West will be flooded by Syrian radicals appears grossly exaggerated. Instead, refugees inclined to move westward are typically pro-Western to begin with.

These results are subject to two caveats. First, our data attests to general trends only. Careful vetting of all refugees is still essential for any country.

Second, a great deal might depend on the welcome refugees receive from the host community. A hostile and discriminatory attitude might produce frustration and radicalize refugees.

The latter scenario, however, rests firmly in the hands of the countries that offer them refuge.![]()

Arie Kruglanski, Professor of Psychology, University of Maryland; David Webber, Assistant professor, Virginia Commonwealth University; Erica Molinario, Postdoctoral Research Associate, University of Maryland, and Katarzyna Jaśko, Researcher in the Institute of Psychology, Centre for Social Cognitive Studies Kraków

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

———-

Bonus video added by Informed Comment:

CBS News: “The state of the Syrian refugee crisis”

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved