By Anne-Ruth Wertheim A special postcard Note 1)

Translation in English: Penny Sandford & Wiesje Wijngaarden

On 18 December 1944 my mother, my sister, my little brother and I were deported to a Japanese internment camp for Jews. By sending him a postcard my mother wanted to notify my father, who had been interned in a men’s camp somewhere far away. The camp we were in and where we had spent a year, was the women’s camp Kramat, right in the centre of Old Batavia. Batavia, now called Jakarta, was then the capital city of the Dutch colony of the Dutch East Indies. Since 1942 the archipelago had been occupied by Japan, which was steadily conquering all countries around the Pacific Ocean. Immediately following the invasion the Japanese had begun sending the Dutch people to internment camps – separating the men from the women and children. Machine guns guarded us night and day, and each morning and evening roll calls were taken. Escape would have been pointless anyway, as our white skins would have given us away immediately among the Indonesians, persons of mixed Indonesian/Dutch origin, Chinese and Japanese people. The reason why we had to leave this time was our Jewish blood, my mother had explained to us.

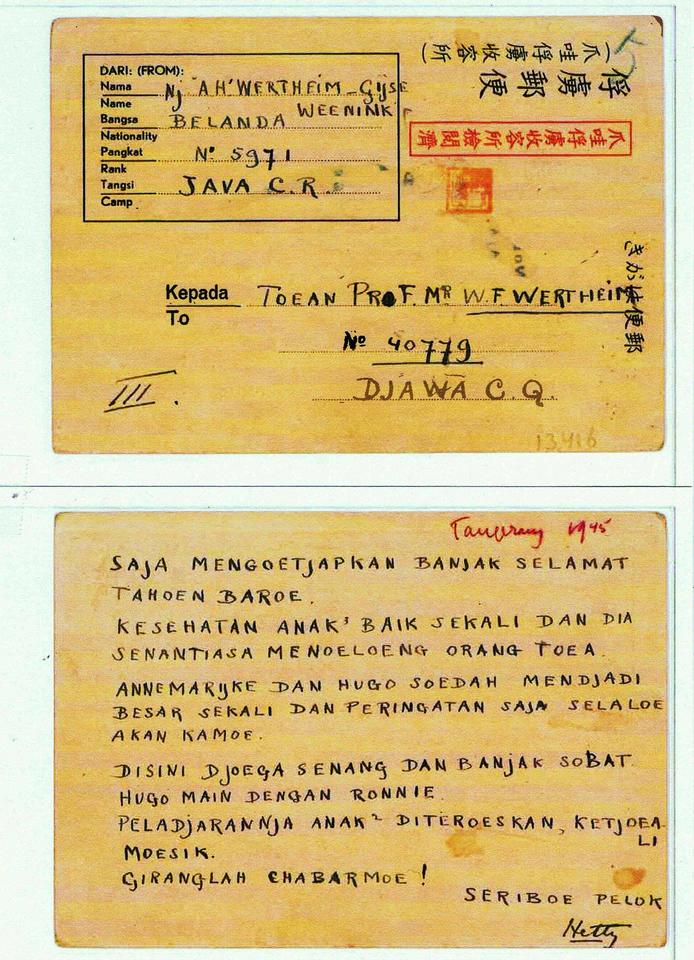

The writing on the postcard:

From: Mrs A.H.Wertheim-Gijse Weenink, Dutch, number 5971, Java C.R. (= district I, Batavia and its surroundings)

To: Professor Mr W.F. Wertheim, number 40997, under it, in a different handwriting than my mother’s: Djawa (= Indonesian for Java) C.Q. (= district II, all other areas on West Java)

On the right a Japanese stamp: postcard

Japanese stamp in red: Approved by the censors of the POW (Prisoner Of War) camps on Java Above it a Japanese stamp saying: Mail from the POW (Prisoner Of War) camps on Java

The Roman III, which was obviously added by the authorities, could be a code.

My mother’s text (after the war she wrote Tangerang 1945 in red pencil at the top of the page):

Wishing you a very happy New Year

The children are in excellent health and are always helpful to the adults

Annemarijke and Hugo are growing up fast and you are always in our thoughts.

It is very pleasant here, too, and there are lots of friends of mine

Hugo playing with Ronnie

Lessons to the children – except for music – continuing

I will be delighted to receive a message from you

A thousand fond embraces

Hetty

It was still dark when we arrived at the Gate and saw some twenty people standing beside a truck, its engine roaring. The three of us had been brought here by close friends of our mother’s, as she herself was in the camp hospital and had to be moved on a stretcher. While the Japanese were nervously beckoning everyone to climb into the back, people were hurriedly exchanging goodbyes with those staying behind and arranging their luggage. We, the children, were lifted up and handed over to people already in the truck. Our mother, fortunately, was allowed to sit beside the driver.

The grown-ups made room for me on the outer edge, so that I could watch the world outside. Cars, bicycle taxis and horse-drawn carriages passed or continued to drive beside us. There were flowering beds bordering clean streets and grand white houses. Wherever I looked I saw colourfully dressed people moving about, as if there was nothing out of the ordinary.

We stopped at Mangarai train station where still more people were standing around waiting on the platform, Jewish people from other camps as it turned out. A girl with a bandaged leg was sitting down on the ground – her name was Naomi and she was to become my best friend in the new camp. The train was pitch dark and most people were crammed onto the luggage piled between the wooden benches along the sides. Our mother luckily had a seat, her injured leg on a suitcase. The small town of Tangerang is only fifty kilometres north-west of Batavia, but the journey took hours because the trains were constantly being shunted or brought to a standstill, while the shutters remained closed. It grew hotter and hotter and furious quarrels kept breaking out.

Then someone tried to open a shutter. The guards immediately started hammering at the shutters with their rifle butts, splintering one wooden slat. We took turns peeping through that crack, and my brother was told to pee through it when the bucket that had been supplied for the purpose was overflowing.

This railway transport had been announced a couple of months before, on 4 September 1944. The Kramat Command had issued an order that all internees whose veins contained even as much as a single drop of Jewish blood, had to be registered so they could be trucked to a separate camp. Japan, as we all know, was an ally of Nazi Germany, and from the very beginning there was a chance that the Japanese occupation forces would get dragged into their anti- Jewish ideology. One had to be alert, for disaster would seep in bit by bit. Earlier, even prior to entering the camp, our mother had recognised a couple of warning signs, a radio speech which contained a negative description of Jews, or a certain German visitor to Batavia, Dr. Wohltat, whom she knew to be a fanatical Nazi.

When the order came through she was scared to death, and lay awake many a night. She wasn’t Jewish herself, but our father was. So her children’s veins contained quite a few drops of Jewish blood. Yet she strongly hesitated whether or not she should have us registered. Experience had taught us that it was dangerous to ignore Japanese orders – brutal beatings and solitary confinement might ensue. But any deportation and the uncertainty of a new, unfamiliar camp involved serious risks. In this case there was yet another danger.

If she registered our names, the possibility would arise that she, being non-Jewish, would have to stay in the Kramat camp, whereas we would be sent to the Jewish camp without her. The Japanese had no scruples taking children away from their mothers, as we had witnessed quite a few times. Periodically, they sent all boys upon their tenth birthday to one or other men’s camp. That was the age the Japanese considered them to be adults and to be able to make women pregnant, which had to be avoided at all cost. Our ages at that time were between eight and eleven.

My father was somewhere far away in a men’s camp, and we didn’t even know whether he was alive or not, let alone whether he had had himself registered as a Jew. Twice a year the men and the women were allowed to write postcards to their spouses in Indonesian from their respective camps, but these seldom arrived, or, if they did, months later. And suppose he had had himself registered, then it depended on the accuracy of the Japanese administration, and whether our camp Command knew about it or not.

After endlessly racking her brains and nightly conversations with her close friends, my mother decided she didn’t want to take the risk and hit upon an ingenious solution: she went to have herself registered as Jewish. This way we could at least stay together and, if necessary, go to the Jewish camp together. This also meant the elimination of an additional risk, the risk of betrayal by fellow internees. After all, every Dutchman would recognise the name of Wertheim as a familiar Jewish name. The Japanese themselves probably didn’t know, but the possibility that an internee would accidentally let slip information could not be ruled out. Solidarity was strong, and people helped each other as much as they could. But living in crammed quarters, starvation, cruel punishments and a sense of hopelessness led to tense situations in which latent prejudices might easily surface, including anti-Semitic ones.

When we arrived at Tangerang Station it turned out we had to walk to the prison, which was kilometres away. And so, in the heat of day, we marched, a long line of thin, shabbily dressed prisoners, barefoot – we had been shoeless for ages – flanked by armed soldiers. We saw how the local population was watching us – most of them with a worried look on their faces, but one or two people couldn’t suppress a contented smile. It wasn’t until much later that we understood how transportations of this kind helped raise the people’s hope that, one day, they would finally be rid of those who had ruled their country for centuries. They knew that the Dutch were locked up and locked in for years, but what was happening there was invisible behind the fences, made of tight woven bamboo mats streaked with barbed wire. The frequent dragging of prisoners from one camp to the other however, spread over the archipelago there were hundreds, you didn’t have to be Jewish for that.

For us children the journey was particularly arduous because besides carrying our own luggage we also had to lug our mother’s, as she was being transported in a lorry together with the other sick people. A Japanese guard was kind enough to take care of my sister’s small violin. Her reaction was one of fear for she thought he might pinch it. However, she soon saw he handled it with great care, meanwhile triumphantly checking around to see whether his fellow guards noticed him. But then a person of higher rank ordered him to return it to my sister.

The Tangerang camp, established in the former juvenile detention centre, was quite different from the camp we had just left behind. Gloomy grey buildings with high halls along covered porticoes and a pungent stench everywhere. Long rows of holes in the ground served as toilets with supports for your feet, where all the gunk collected due to a lack of water. Every hall had rows of two-tier wooden bunk beds to accommodate eighty people. We were assigned the lower beds and diagonally across from us were Mrs Abram and her young boys Ronnie and Ido whom we knew from before the war.

The daily roll calls here didn’t take place outside in a centrally located open field but in the porticoes outside our dormitories. Upon hearing the wooden gong you had to stand in rows of five immediately and bow as soon as the Japanese walked by. A few days after our arrival the gong suddenly sounded at midday. And as we were standing to attention a stretcher with a small body covered from head to toe by a sheet was carried past us. It turned out to be the little girl from the dormitory next to ours who had collapsed during the journey here. The previous night we had heard her mother anxiously calling out that she couldn’t wake her daughter for the roll call.

When the six months had passed since my mother had been allowed to send her last postcard to my father, she wanted to notify him that we were now in a Jewish camp. Note 2). Everyone always wrote these postcards with the utmost care. They had to be written in Malay, later called Bahassa Indonesia, only a strictly limited number of words was allowed, and the trick was to include as much information as you could without being found out by the censors. And if you used but one word of Dutch you ran an even greater risk that your card would not arrive. And to think that most Dutch women knew just about enough Malay to be able to order their servants about and go shopping in the Pasar. Our mother’s Malay reading, writing and speaking skills, however, were excellent so she was able to help a great many fellow prisoners.

In writing this postcard she had yet another complication to deal with. After all, she didn’t know whether my father had registered in his camp as a Jew and if that was not the case, she should not betray him. Miraculously this postcard not only reached my father – albeit months later -, it also survived until today Note 3). Funnily enough the first time she uses the word anak (=child), she doesn’t use the symbol for square (2) – which in the Indonesian language indicates the plural – but instead she writes the number 3. This is how he knew all was well with the three of us and in the following sentence she managed to win a word by joining the names of my sister and me, Marijke and Anne-Ruth to Annemarijke.

Where my mother wrote Hugo main dengan Ronnie (Hugo is playing with Ronnie) she wanted to let him know that we were in a Jewish camp. He had to be alerted to the fact that she did mention a friend of Hugo’s but no friends of my sister’s and mine, whereas she was known to always share her attention meticulously between her three children. She also wanted him to wonder why – out of all his friends – she should have chosen Ronnie Abram. There used to be a few Jewish families in Batavia, but it was common knowledge that the Abrams upheld Jewish traditions.

When she told us about this after the war, she thought that – for safety’s sake – she had added to those two little boys playing: in the play pen. But when, after her death, we finally discovered the postcard and read the text, we found that her memory had played her false. She had hoped he would understand there was something odd about the play pen for by that time the two boys were already eight – too old to play in a pen. And of course play pen had to stand for prison.

Preceding the sentence about the playing boys she had dropped a few more hints in her text. She wrote Disini djoega senang dan banjak sobat (It is pleasant here too and there are many friends of mine). From the words here too he could deduce that we had moved to another camp, and that her mention of Ronnie’s name immediately after these words was no coincidence either. Finally she had hoped he would understand from the many friends she had found here that this was a Jewish women’s camp for he knew that many of her friends were Jewish. In hindsight this was, of course, asking quite a lot!

After the war it turned out that he had indeed got the message that we had been transported to another camp, but not that it was a Jewish camp. Together with three of his friends who were also Jewish, he had decided not to sign up when the order came through. They hoped that their being Jewish could remain a secret for the Japanese and indeed it did. That they had dared to do this was certainly due to the fact that men, without their children around them, were in a position to take greater risks. In their case there was an additional reason why the chance of being sent off to another camp was small. For in their own camp there was a Jewish barrack block which the prisoners called ‘Tel Aviv’. But, unlike the Jewish men who had registered and consequently had ended up in that barrack block, my father and his friends had been swayed by the thought that one should not provide the Japanese with more information than was strictly necessary. And in any case you should not give them details they might use to treat you differently from the other internees.

After the war we often spoke about the inhuman choice our mother was faced with, our transportation to Tangerang and her postcard to my father. On such occasions my mother would always hasten to add that her desire to show solidarity with him being a Jew had also played a role in her decision, at which he would give a shy little smile. He himself would also have been desperate if he had had to weigh all those threats and risks, especially the possibility of losing your children, so he considered her solution inventive and loving. However, if they had had the opportunity to think things over together, his decision might still have veered towards not registering. He estimated that the chance of our Jewish blood being found out would be slightly smaller than the dangers involved in transportation and an unknown camp. And he, more so than she, was convinced that you should disclose as little as possible to whatever oppressor or occupier. They always were in complete agreement, however, that talking with the benefit of hindsight is always easy.

Note 1) It was a fascinating process for my sister Marijke The-Wertheim, my brother Hugo Wertheim and me to weigh the details of our sometimes slightly differing memories and to arrive at a mutual picture.

Note 2) Many thanks to Joss Wibisono for the Indonesian translation of the postcard and to Ethan Mark for the Japanese.

Note 3) The postcard is carefully preserved in the archives of the Jewish Historical Museum in Amsterdam.

Via Groene.nl by author’s permission

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved