By John Foster | –

(Monitor) – When Washington dubbed American gas exports “Freedom Gas” this year, it signalled a new salvo in U.S. competition with Russia. The target behind the branding is Europe, the largest gas market outside North America. With a bonanza of gas from fracking, the U.S. aims to become the world’s largest gas exporter by 2024. It will need markets for this production.

Natural gas moves around the world by pipeline and tanker. This year, the U.S. became the world’s third largest exporter of liquefied natural gas (LNG) as four new liquefaction plants came online. President Trump exulted, “we’re shipping freedom and opportunity abroad.”

Canada is looking to increase gas exports too. In northeast B.C., companies are fracking for gas with plans to export it to Asia. And just this summer, Pieridae Energy announced its hope to pipe Alberta gas to a proposed LNG terminal in Goldboro, Nova Scotia, for eventual export to Germany.

U.S. LNG — and the Canadian stuff — will face stiff competition from Russia, which already has two LNG plants up and running and is planning two more. Foreign partners include Total, Shell and ExxonMobil. From the Russian Arctic, ice-breaking tankers move LNG to Europe and Asia. From the Russian Far East, LNG tankers ply to Asia.

Russia is the world’s largest gas exporter, mostly by pipeline. And Europe is a vital energy market for Russia. The European Union imports 70% of its gas; Russia is the biggest source, then Norway and Algeria. U.S. gas is more expensive than other sources. Perhaps that is why, as the Harper government tried with “ethical oil,” the U.S. is appealing to ideology.

Europe has been using Russian gas since the 1960s, and in a real way, east-west pipelines helped build trust. Washington has consistently opposed Russian gas to Europe. Its envoys have visited Bulgaria, Greece and Germany repeatedly to vigorously discourage new pipelines from Russia. The Europe- ans excluded natural gas from Russian sanctions in 2014: they wanted Russian gas to keep flowing. Undaunted, the U.S. continues its efforts to curb European use of Russian gas, claiming the issue is energy security.

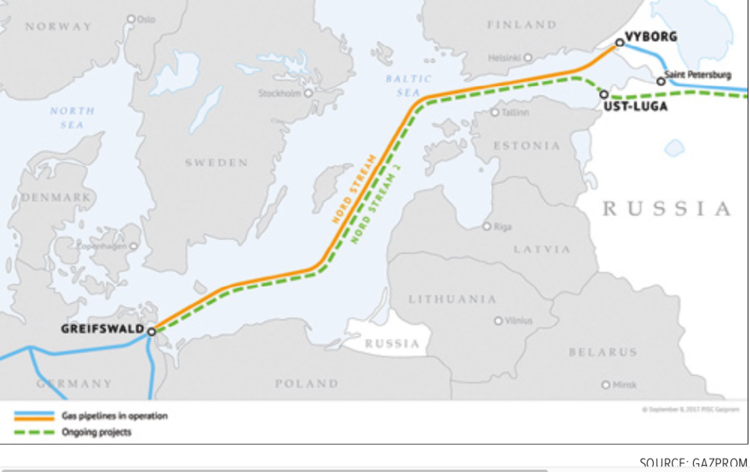

Traditionally, Russian gas flowed to Europe through pipelines through Ukraine. In recent years, Ukraine’s payment problems, corruption, and hostility to Russia have threatened gas exports. For Russia, the European market is vital to government revenues and exchange earnings. In a quest for more reliable routes, Russia seeks new pipelines bypassing Ukraine to the north and south.

To the north, Russia built Nord Stream with European partners — a direct route to Germany under the Baltic Sea. Now a parallel line, Nord Stream 2, is three-quarters built. The project is highly divisive. Central Europe wants it, welcoming a diversity of supply routes. Eastern Europe opposes it, fearing loss of transit fees from existing routes. Poland increasingly prefers “Freedom Gas,” i.e., American LNG. The U.S. is going all out to kill Nord Stream 2, threatening sanctions on European participants.

To the south, Russia is building TurkStream, two parallel lines under the Black Sea to Turkey. One will bring gas to the Turkish market; the other is intended for Europe via Greece or Bulgaria. European Commission approval of new connecting pipelines is by no means certain. Working hand-in-hand, Brussels and Washington favour rival sources: 1) gas from the United States; 2) gas by new pipeline from Azerbaijan; and 3) offshore gas from Cyprus and Israel. All are more expensive than Russian gas. It’s a question of politics, not economics.

Broadly speaking, Canada supports U.S. foreign policy in Europe, with Canadian troops stationed in Latvia and Ukraine and our sanctions on Russia.

Ignored is gas from Iran, a country with the world’s second largest reserves of the stuff. Iran produces gas for its own use and for neighbours Iraq and Turkey. For many years, the U.S. has blocked Iran’s plans for other pipelines, including one to its neighbour Pakistan. The Iranian section is built. The Pakistani section languishes despite desperate gas shortages. The U.S. has threatened sanctions if Pakistan goes ahead.

Instead, Washington continues to promote a rival pipeline planned from Turkmenistan to Pakistan and India, passing through Afghanistan. Twelve years ago, U.S. ambassador Richard Boucher asserted, “One of our goals is to stabilize Afghanistan,” to link South and Central Asia “so that energy can flow to the south.” Four years later, in 2011, then Secretary of State Hillary Clinton offered more support for the proposed pipeline. Turkmenistan, on Afghanistan’s northern border, has the world’s fourth largest reserves. It used to export gas to Russia. Now it exports big-time to China via pipelines built peacefully since the Afghan War began.

Natural gas is part of the power politics among countries. The term “Freedom Gas” shows the rivalry extends beyond market competition. It’s part of a U.S. geopolitical game to weaken America’s nemesis Rus- sia and control Europe through its energy sources. Broadly speaking, Canada supports U.S. foreign policy in Europe, with Canadian troops stationed in Latvia and Ukraine and our sanctions on Russia. Unwittingly or strategically, Canada is a player too.

Republished with the author’s permission from Monitor: Progressive News, Views and Ideas

John Foster is author of

Oil and World Politics: The Real Story of Today’s Confict Zones (Lorimer Books, 2018).

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved