By Ashish Sinha and Gayatri Kathayat | –

Ancient Mesopotamia, the fabled land between the Tigris and the Euphrates rivers, was the command and control center of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. This ancient superpower was the largest empire of its time, lasting from 912 BC to 609 BC in what is now modern Iraq and Syria. At its height, the Assyrian state stretched from the Mediterranean and Egypt in the west to the Persian Gulf and western Iran in the east.

British Museum, CC BY-ND

Then, in an astonishing reversal of fortune, the Neo-Assyrian Empire plummeted from its zenith (circa 650 BC) to complete political collapse within the span of just a few decades. What happened?

Numerous theories attempt to explain the Assyrian collapse. Most researchers attribute it to imperial overexpansion, civil wars, political unrest and Assyrian military defeat by a coalition of Babylonian and Median forces in 612 BC. But exactly how these two small armies were able to annihilate what was then the most powerful military force in the world has mystified historians and archaeologists for more than a hundred years.

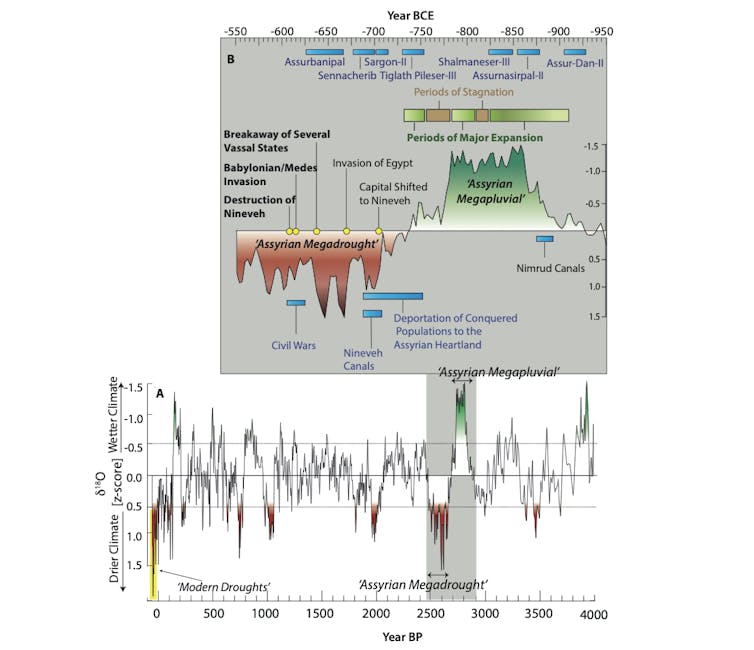

Our new research published in the journal Science Advances sheds light on these mysteries. We show that climate change was the proverbial double-edged sword that first contributed to the meteoric rise of the Neo-Assyrian Empire and then to its precipitous collapse.

New York Public library digital collections, CC BY-ND

Booming right up to an unexpected bust

The Neo-Assyrian state was an economic powerhouse. Its formidable war machine boasted a large standing army with cavalry, chariots and iron weaponry. For over two centuries, the mighty Assyrians waged relentless military campaigns with ruthless efficiency. They conquered, plundered and subjugated major regional powers across the Near and Middle East, as each Assyrian king tried to outshine his predecessor.

Ashurbanipal, the last great king of Assyria, ruled this vast empire from the ancient city of Nineveh, the ruins of which lie across the Tigris River from modern Mosul, Iraq. Nineveh was a sprawling metropolis of unprecedented size and grandeur filled with temples and palace complexes, with exotic gardens that were watered by an extensive system of canals and aqueducts.

And then it all ended within just a few years. Why?

Our research group wanted to investigate climate conditions over the few centuries when the Neo-Assyrian Empire took hold and then eventually collapsed.

Building a picture of climate 2,600 years ago

For clues about rainfall patterns over northern Mesopotamia, we turned to Kuna Ba cave, located near Nineveh.

Our colleagues collected samples from the cave’s stalagmites. These are the cone-like structures that point upward from the cave floor. They grow slowly, from the ground up, as rainwater drips down from the cave ceiling, depositing dissolved minerals.

Ashish Sinha, CC BY-ND

The rainwater naturally contains heavy and light isotopes of oxygen – that is, atoms of oxygen that have different numbers of neutrons. Subtle variations in the oxygen isotope ratios can be sensitive indicators of climatic conditions at the time the rainwater originally fell. As stalagmites grow, they lock into their structure the oxygen isotope ratios of the percolating rainwater that seeps into the cave.

We painstakingly pieced together the climatic history of northern Mesopotamia by carefully drilling into stalagmites, across their growth rings, which are similar to those of trees. In each sample, we measured the oxygen isotope ratios to build a timeline of how conditions changed. That told us the order of events but didn’t tell us the amount of time that elapsed between them.

Luckily, the stalagmites also trap uranium, an element that’s ever-present in trace amounts in the infiltrating water. Over time, uranium decays into thorium at a predictable pace. So the dating experts on our research team made scores of high-precision uranium-thorium measurements on stalagmite growth layers.

Together these two kinds of measurements let us anchor our climate record to precise calendar years.

Unusual wet period, then massive drought

Now a direct comparison of the stalagmite climate record with the historical and archaeological records from the region was possible. We wanted to place the key events of Neo-Assyrian history into the long-term context of our climate reconstruction.

We found that the most significant expansion phase of the Neo-Assyrian state occurred during a two-centuries-long interval of anomalously wet climate, as compared with the previous 4,000 years. Called a megapluvial period, this time of unusually high rainfall was immediately followed by megadroughts during the early-to-mid-seventh century BC. These ancient dry conditions were as severe as recent droughts in Iraq and Syria but lasted for decades. The period marking the collapse of the Neo-Assyrian Empire occurred well within this time frame.

Ashish Sinha, CC BY-ND

Mindful of the caveat that correlation doesn’t imply causation, we were interested in how this wild climate swing – an unusually rainy period that ended in drought – could have influenced an empire.

While the Neo-Assyrian state was huge in its final few decades, its economic core was always confined to a rather small region. This relatively small area in northern Mesopotamia served as a primary source of agricultural revenues and powered Assyrian military campaigns.

We argue that nearly two centuries of unusually wet conditions in this otherwise semi-arid region allowed for agriculture to flourish and energized the Assyrian economy. The climate acted as a catalyst for the creation of a dense network of urban and rural settlements in the unsettled zones that previously hadn’t been able to support farming.

Our data show the wet period abruptly ended and the pendulum swung the other way. In the grips of recurring megadroughts, the Assyrian core and its hinterlands would have been engulfed within a “zone of uncertainty” – a corridor of land where the rainfall is highly erratic and any rain-fed agriculture comes with a large risk of crop failure.

Repeated crop failures likely exacerbated the political unrest in Assyria, crippled its economy and empowered the adjacent rival states.

Uncertain climate, unsustainable growth

Our findings have current-day implications.

In modern times, the same region that once constituted the Assyrian core has been repeatedly struck by multiyear droughts. The catastrophic drought of 2007–2008 in northern Iraq and Syria, the most severe in the past 50 years, led to cereal crop failures across the region.

Droughts like this one offer a glimpse of what Assyrians endured during the mid-seventh century BC. And the collapse of the Neo-Assyrian Empire offers a warning to today’s societies.

Climate change is here to stay. In the 21st century, people have what Neo-Assyrians did not: the benefit of hindsight and plenty of observational data. Unsustainable growth in politically volatile and water-stressed regions is a time-tested recipe for disaster.

[ You’re too busy to read everything. We get it. That’s why we’ve got a weekly newsletter. Sign up for good Sunday reading. ]

Ashish Sinha, Professor of Earth and Climate Sciences, California State University, Dominguez Hills and Gayatri Kathayat, Associate Professor of Global Environmental Change, Xi’an Jiaotong University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved